Last year at the Super Bowl, Rihanna danced on a platform suspended high above the field at State Farm Stadium in Arizona.

It was her first live show in five years, and she moved effortlessly from hits like “We Found Love” to “Diamonds,” in a red leather corset and baggy flight-suit unzipped to emphasize what viewers suspected was a baby bump. (It was.)

Her savviest move came halfway through her set, a moment that made clear why Rihanna couldn’t pass up putting on a free concert in the desert. (Super Bowl halftime performers don’t get paid.)

As she prepared to sing the intro to “All of the Lights,” a dancer handed Rihanna a sleek white makeup compact. Huh? The pop star quickly blotted Invisimatte setting powder from her Fenty beauty line across her cheeks.

The moment didn’t last five seconds, but the internet went nuts.

Google search traffic for Fenty skyrocketed compared to the previous week, and the company was ready for it, adding a special Super Bowl section to its website. AdWeek reported the performance earned Fenty $5.6m in media value over the next 12 hours.

“I think if you asked Rihanna if [performing at the Super Bowl] was worth it,” said Matt McAllister, a Penn State University professor who researches Super Bowl advertising, “she would say it was worth it.”

The Super Bowl’s primary purpose may be to crown the top team in professional football (and prop up the American chicken wing industry). But artists who perform at halftime are the biggest winners. In a fragmented cultural landscape, they’re granted the single-largest advertising stage in the world — for free.

The birth of the can’t-miss halftime show

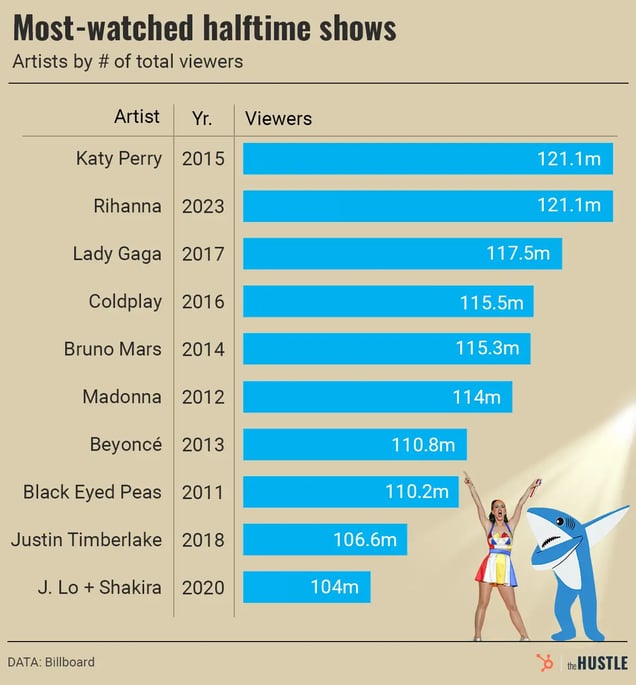

Long before Katy Perry mesmerized the world with dancing sharks at the 2015 Super Bowl, figure skaters Brian Boitano and Dorothy Hamill and singer Gloria Estefan headlined a halftime show alongside dancing snowflakes.

“Come to Minnesota,” Hamill implored at the start of the show, “where our winter’s the hottest time of the year!”

It was the 1992 Super Bowl in Minneapolis. As part of a show titled Winter Magic, the dancers frolicked around a stage bookended by two giant inflatable snowmen, slightly larger than you’d see in a suburban front yard. Before Estefan sang, an orchestra performed a rendition of the Nutcracker’s “Russian Dance” and “Walking in a Winter Wonderland.” (It was a month after Christmas.)

Scenes from the 1992 Super Bowl halftime show. (YouTube via Buckets and Tap Shoes)

Unfortunately, trippy precipitation was not nearly as popular as trippy Jaws. The Super Bowl’s audience tumbled from a 40 rating during the game — meaning 40% of American television viewers tuned in — to 33 at halftime, as millions of viewers changed the channel from CBS to Fox, which aired a special episode of the Keenen Ivory Wayans sketch comedy show “In Living Color.”

Jim Steeg, an NFL employee who programmed the Super Bowl from 1979 to 2005, knew something had to change.

Since the inception of the Big Game in 1967, the league had emphasized spectacles for the halftime show — marching bands from Grambling State University and Southern University, Mickey Rooney, George Burns, Up with People. They entertained the 50k+ spectators who attended the game but didn’t always translate for the TV audience.

The remedy, Steeg tells The Hustle, was “to go find as big of a name as we could.”

About a month later, Steeg and the NFL met with Michael Jackson’s manager. It wasn’t easy. They had to convince Jackson to perform for free at an event he knew almost nothing about.

“They really had no idea what we were talking about — not just the halftime show, but Super Bowl, football, all that sort of stuff,” Steeg recalls.

It took three meetings, but the NFL booked the King of Pop for the 1993 halftime show, swaying his manager by noting the game’s extraordinary reach. The performance would be televised in ~180 countries, giving Jackson an opportunity to put on a show for fans who would never see him on tour.

The NFL budgeted ~$2.2m for the show — roughly double what it budgeted in the late ’80s. In a haze of firework smoke, Jackson, dressed in a black military jacket embossed with gold, played his oeuvre of hits. TV ratings were higher for Jackson’s performance than for the actual game, which drew a then-record number of viewers. Countries where he’d never perform basically watched him play a concert.

The Hustle

For a couple years, Steeg says, prominent artists didn’t want to follow Jackson because they worried about living up to his standard. But Diana Ross’ performance in 1996 elevated the halftime show again, giving the NFL influence to consistently book A-list music acts. Artists who originally declined, such as Bruce Springsteen, eventually signed up for the gig.

“They knew… there was nothing they could ever do that could get more eyeballs on them than doing the Super Bowl,” Steeg says.

Especially these days.

The only thing that matters on TV

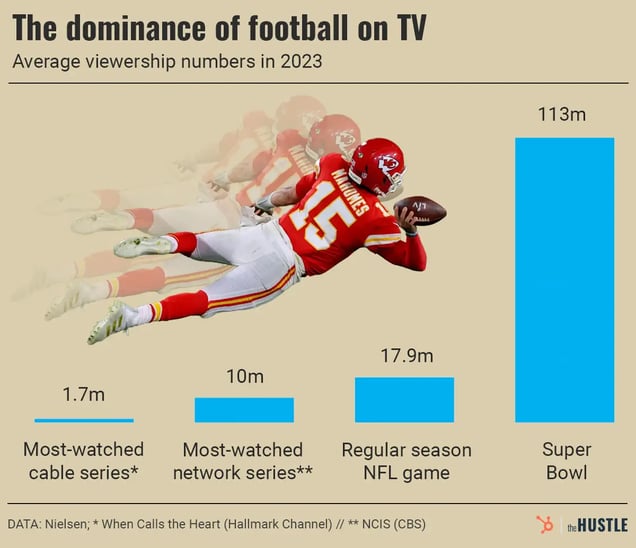

Eyeballs are a scarce resource now, if you want them in one place at the same time. The mass audiences that once flocked to television have fragmented because of streaming, YouTube, and TikTok.

- In 2023, only eight out of all 153 linear TV channels averaged an audience of more than 1m viewers across their entire catalog of prime-time television programming.

- The best-performing series on network TV, NCIS, averaged viewership numbers that would’ve made it the 23rd most-watched series in 2000.

The decline has raised an ages-old philosophical question: If a commercial airs at 8:30pm ET and fewer than 3m people bother to watch, is it even capitalism?

Fortunately, there’s an exception to the rule of television decline: professional football. Of the top 100 highest-rated television broadcasts last year, 93 were NFL games, according to Nielsen. The league averaged 17.9m viewers per broadcast — its second-highest number since 1995.

That’s more than 2x the average audience for NCIS and more than 10x the average audience for Hallmark’s When Calls The Heart, the most popular series on cable.

The Hustle

And then there’s the Super Bowl, which is in a class of its own. The 2023 game averaged an audience of 113m and a 40 rating. Brands paid ~$7m for 30-second advertisements, nearly 100x the going rate for an ad during The Masked Singer, a popular prime-time show.

While brands must splurge at the Super Bowl, halftime artists don’t have to pay anything (although some, like the Weeknd, have contributed money to enhance production).

“And… you’re getting 12 minutes of airtime,” says Ricky Kirshner, executive producer of the Super Bowl halftime show from 2007 to 2020. “So obviously, it’s a pretty lucrative position to be in.”

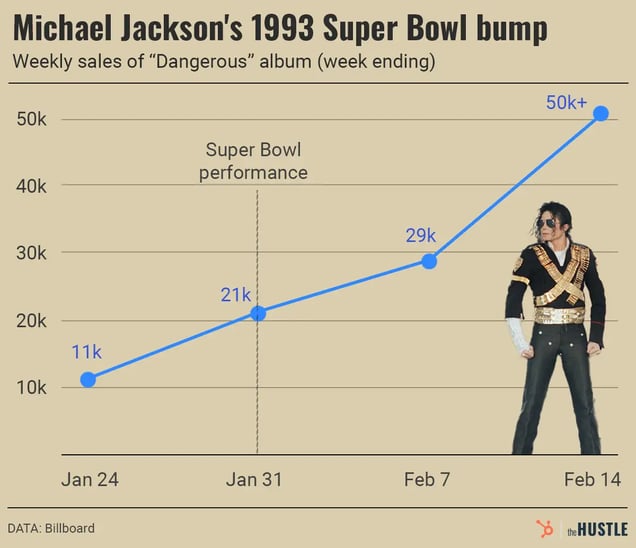

Jackson’s halftime show, combined with appearances at the Grammys and American Music Awards, helped push Dangerous, an album he released two years earlier, from barely inside the Billboard top 100 into the top 10.

It was the start of a trend: U2 saw sales of three albums more than double after a halftime performance, according to Billboard, and albums by Dr. Dre and Eminem entered the top 10 for the first time in more than a decade when they performed in 2022.

The Hustle

But the shows do more than move albums and inflate streaming numbers. Last year, through her de facto commercial, Rihanna built on her reputation as a bona fide entrepreneur.

With so much clout at stake, the slot has become highly coveted. Although record labels and agents pitch their artists and halftime producers make suggestions, the NFL always gets the final say, Kirshner says, and favors acts with lengthy music catalogs and fans across multiple generations.

Occasionally, an up-and-comer gets the nod. In 2014, Kirshner pushed hard for Bruno Mars, who had released only two studio albums.

“I took it to [the NFL],” Kirshner recalls, “and I said, ‘I think Bruno’s ready for this.’”

Bruno Mars performed at the 2014 Super Bowl in East Rutherford, New Jersey. (Getty Images/Elsa)

Mars’ performance earned mostly positive reviews. He also exhibited the marketing acumen of a seasoned veteran: The day after the Super Bowl, tickets for his upcoming tour went on sale.

Purple rain

Even when Michael Jackson transformed the Super Bowl halftime experience, not everyone enjoyed the show.

“Sadly the Jackson interlude fitted perfectly into the orgy of commercials and commercialism that was Super Bowl XXVII,” wrote a Canadian critic.

The upside of the Super Bowl halftime show — an unparalleled marketing opportunity tied to a multibillion dollar league and corporate sponsors like Apple — can also be a downside.

When Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers performed in 2008, Petty admitted that the NFL “strongly hinted” that he shouldn’t perform songs with marijuana references like “Last Dance With Mary Jane” and “You Don’t Know How It Feels.” Petty was accused of playing it safe and ginning up interest for an upcoming tour.

“It really wasn’t a great performance,” wrote the Chicago Tribune. “It was more of a Tom Petty commercial.”

More recently, Adele explained to fans at a 2016 concert that she turned down the halftime show, saying “that show is not about music.” And when Rihanna originally turned down the Super Bowl out of solidarity for quarterback Colin Kaepernick in 2019, she claimed she didn’t want to be a “sellout.”

“Even someone with an ostensible Midas touch like Rihanna is felled by the albatross of capitalism,” lamented Teen Vogue, after she changed her mind and performed in 2023.

Kirshner, for his part, doesn’t consider the halftime show an advertisement.

“I think calling it an ad is a bit crude because I think most of these acts have earned being there. And it’s not just a commercial thing,” he says.

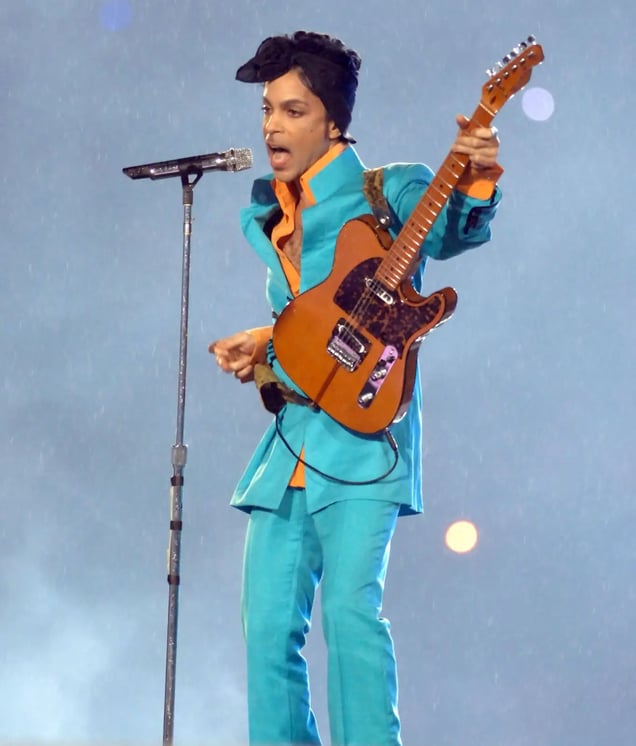

Prince dazzling millions at the Super Bowl in 2007. (Getty Images/Jeff Kravitz)

There’s no better example for that than Prince. The pop star performed at the 2007 Super Bowl. When an NFL representative visited his Minneapolis house to gauge interest, Prince played DVDs of previous Super Bowl halftime shows, critiquing them and explaining what he would’ve done differently.

At the Big Game in Miami, he played in the pouring rain, delivering an iconic performance. He spent nearly a quarter of his set playing a medley of Bob Dylan and the Foo Fighters — a song he certainly wasn’t promoting because it didn’t appear on his albums.

After the set, Kirshner saw Prince in the stadium suites.

“I said, ‘That was amazing. I wish I could hug you,’” Kirshner recalls. “And he said, ‘Of course, you can hug me.’ And so I hugged Prince.”