A few years ago, Kimi Coy and her mother, Carolyn Benyshek, booked a mother-daughter trip to Singapore.

Benyshek flew 2.5 hours from Colorado Springs to meet Coy in Atlanta. The pair took a 15-hour connecting flight to Narita, Japan, then boarded another 7-hour flight to Singapore.

Once they were finally in Singapore, Coy and Benyshek scoped out the amenities of Changi Airport (one of the world’s best), visited a shopping mall, did a hop-on/hop-off bus tour, and slept about four hours at a hotel.

Then, they dashed off to the airport at around midnight to fly home.

Despite spending less than 24 hours in Singapore, the journey was successful: The airline miles propelled Coy into platinum status on Delta, putting her in an elite group of frequent flyers and qualifying her for several perks.

“Sacrificing that one weekend was absolutely worth it,” said Coy, who also made a similar trip to Budapest.

Trips like this are known as mileage runs.

These are flights where the mileage is the purpose, not the destination. Travelers take them to earn or maintain elite status with airlines like Delta, United, American, Southwest, or Alaska.

But are the miles really worth the trouble? And how do mileage runs stack up in a post-pandemic world of higher prices and fewer flights?

The golden age of mileage runs

Starting in the 1980s, airlines began to develop loyalty programs, rewarding frequent flyers with free flights.

The programs grew more complicated over the years as airlines created status tiers based on miles traveled while also dangling opportunities to accrue double or triple miles on select trips.

Kimi Coy (left) and her mother Carolyn Benyshek have made mileage runs to Singapore and Budapest. “It’s in my family’s DNA to do this,” Coy said. (via Kimi Coy)

Thus, the mileage run was born.

Their popularity skyrocketed in the early 2000s when travel-related newsletters, message boards, and websites popped up, discussing the trend of mileage runs and helping frequent flyers identify trips.

- Ideal mileage runs involve long flights and relatively low fares. Experts in the community say they should top out at ~4-5 cents per mile earned if you’re flying coach and ~6-7 cents for business class or first class.

- People usually do mileage runs late in the year when they realize they need a certain number of miles to leap into a desired status tier.

- In the truest form of a mileage run, the traveler doesn’t leave the airport — although many mileage runners will spend a few hours to a couple of days in their destination city.

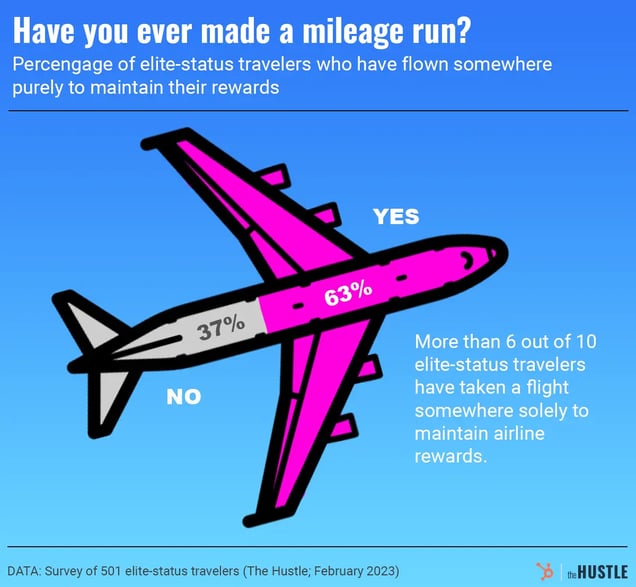

In 2006, one airline industry observer estimated 1m mileage runs were made annually. A Hustle survey of ~550 elite-status flyers earlier this month revealed ~63% had made at least one mileage run.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

A few years ago, Kanon Cozad, a Kansas City-based tech consultant, realized he needed a few thousand miles to maintain his American Airlines status. He flew from Kansas City to Chicago to Seattle to Los Angeles to Phoenix to Kansas City, not leaving any of the airports.

“It was a completely silly thing to do,” Cozad said. “But I rationalized it in my own mind because of the tangible benefits that I would continue to get throughout the next year.”

The upgrade math

To Cozad, the benefits of mileage runs are comfort. He believes airlines have made travel progressively “less pleasant” and enhancements provided by elite status are “something to be held onto once you get it.”

Elite status varies depending on the airline but typically comes with several perks:

- Fewer lines at the airport, the ability to board early, and free checked baggage.

- Improved service from airlines. Elite travelers typically get first dibs on replacement flights during weather or mechanical delays.

- Mileage multipliers. Certain loyalty tiers lead to getting 1.5x or 2x miles, which help accrue rewards points faster.

There are also financial reasons for why spending ~$1k-$2k on random mileage runs could save a frequent flyer money in the long run: upgrades.

Elite-status holders are more likely to be upgraded to first class or business class. A domestic flight upgrade could easily be worth a few hundred dollars. On an international flight, where first-class seats can cost $10k, the upgrade could be worth thousands.

A traveler enjoying an upgraded seat (Getty Images)

But no matter the potential benefits, you’re still embarking on long journeys in the air without a major reason for visiting the destination.

Chris Carley, owner and editor of the website Eye of the Flyer, says the value derived from a mileage run “depends on the person.” Carley is an aviation geek, who enjoys planes and visiting airports, especially when he travels with his wife, another mileage-run devotee.

“This is something my wife and I do for dates because we love traveling,” Carley said. “We have to turn our phones off. There’s nothing to distract us. We have time to sit and talk.”

Last year, Jason Merhaut needed a few thousand miles to make the leap from silver to gold status on United and booked a trip from New York to London. He went to a Fulham soccer game, spent the night, and flew home.

“It’s the old adage, ‘If you’ve flown coach all your life and fly first class you never want to fly coach again.’ It’s the same with me for status,” he said.

Merhaut, however, is completely aware that mileage runs are crazy. “I just jokingly refer to myself and my friends who do this as idiots,” he said.

Are mileage runs dead?

Ask somebody who’s gone on several mileage runs, and they’ll get nostalgic, pining for the 2000s and early 2010s when mileage runs were both more common and more beneficial.

These days, plenty of people say the mileage run is dead. At the least, most frequent flyers agree that mileage runs are not as fruitful as they used to be.

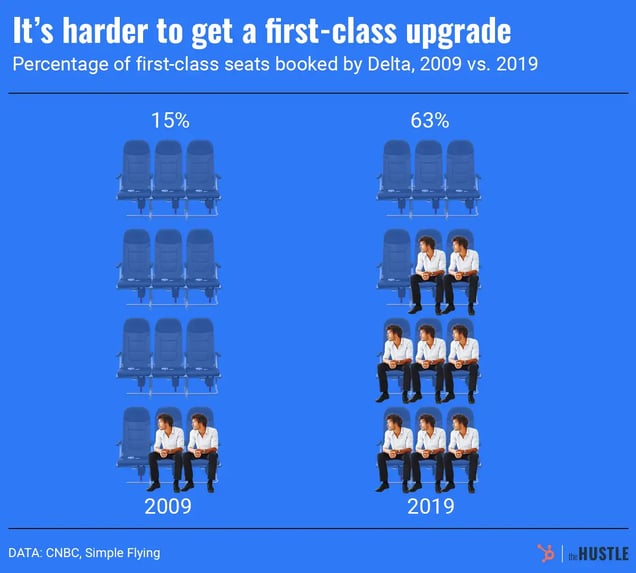

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

There are a number of reasons for this:

- Starting around 2015, airlines like Delta and United stopped awarding status purely on miles. Travelers now earn loyalty points through a mix of miles traveled, cost of fare, and class of fare, as well as money spent on airline-related credit cards.

- Cheap fares became less common, making it harder for travelers to accrue miles for a low cost. On Delta, passengers who fly Basic Economy do not earn any miles.

- With credit card spending part of the equation, more travelers reached elite levels, diluting the benefits. On some airlines, credit card spending means you can reach elite status without ever boarding a plane, a positive for environmental advocates who have suggested airlines untether status from frequent travel.

In the past, people could use mileage runs to spend relatively little to gain status and use that status to enjoy significant perks.

Now, they often make sense only for business travelers who need a few extra points for their loyalty program or hard-core mileage runners who have found ways to benefit despite the adjusted rules.

René de Lambert, who previously operated Eye of the Flyer and sent newsletters highlighting mileage-run opportunities, notes that frequent flyers can still book flights on “partner” airlines — such as AeroMexico for Delta — where a cheap ticket price doesn’t limit the miles-earning power of the flight.

de Lambert booked what he described as “a whopper of a mileage run” on AeroMexico last year: New York to Mexico City to Madrid — where he attended a flamenco show — back to Mexico City and back to New York. He did it twice.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Since the pandemic de Lambert, an elite-status traveler with Delta, is beginning to question the value of mileage runs, citing “crazy prices,” declining customer service, and a glut of elite travelers because of airlines’ decisions to extend 2019 status through 2022.

Upgrades were already harder to come by as airlines built new strategies around selling first-class seats, and the tighter scheduling since the pandemic made them rarer still.

For 2023, Delta has modified its loyalty program so flyers must spend at least $20k on flights to earn the highest status levels, up from $15k in recent years.

That decision may restrict elite benefits to a smaller group of people, but it also means mileage runs — which are valuable when little money is spent — lose more of their benefit.

The year 2022, de Lambert said, “was my last year of mileage running.”

An airplane lands at Los Angeles International Airport (David McNew / Getty Images)

Kimi Coy and her mom have scaled back, too.

For the last few years, Coy hasn’t gone on any mileage runs. The pandemic and her two young children have made it difficult to spend a long time in the air. She also realized her chances at upgrades aren’t what they used to be, making status less appealing.

But Coy misses the mileage runs. At the end of the year, she would compare her mileage levels with her mother and sister and book trips together, turning them into a family tradition.

On those international flights, Coy read books, watched movies, slept, and enjoyed a level of peace and quiet she doesn’t get to experience in her hectic life.

“It sounds luxurious right now,” she said.