In the winter of 1979, a powerful Chicago political dynasty began to collapse.

Michael A. Bilandic, a cog in Richard J. Daley’s political machine, lost the mayoral election in a stunning upset. But there was a simple reason for the defeat: Bilandic didn’t clear the snow quickly enough.

After a forecast for a couple inches, a blizzard hit Chicago that January. Buses and trains didn’t run for days, residents couldn’t find anywhere to park their cars, and plows took forever to reach neighborhoods — unless you were lucky enough to live on the same block as Bilandic.

The lesson? Don’t take snow lightly.

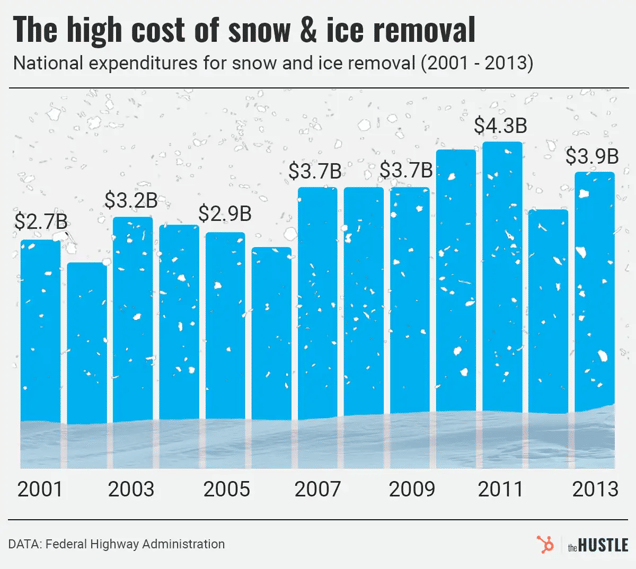

Beyond closures and clogged roads, it can come with steep financial costs. According to a study from the Federal Highway Administration, the nation’s tab for snow and ice removal can be upwards of $4B per year.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Every year, cities and states must decide how to budget for random winter weather events. When they aren’t sufficiently prepared, the costs accumulate.

Where do those billions of dollars go? And how do cities plan for unpredictable weather events?

Salt, snow plows, and brine

Rick Nelson is a coordinator for the Snow and Ice Pooled Fund Cooperative Program, a group that researches the best strategies for winter weather maintenance.

He describes equipment, materials, and staffing as “the trinity” of snow cleanup.

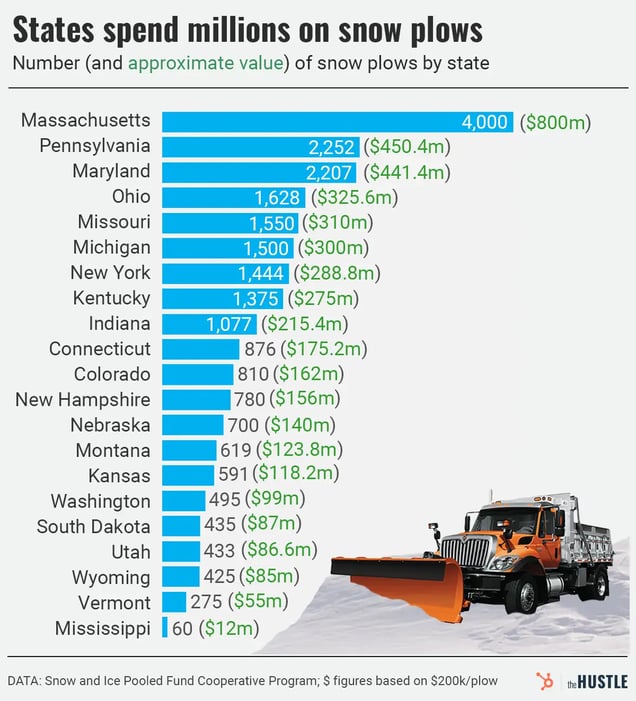

Among the most important pieces of equipment are snow plows, which cost cities and states ~$200k each. States have their own fleets and often contract with companies to use more plows as needed.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

For materials, government agencies typically purchase salt and sand and mix their own salt brine, which ends up costing them ~$0.10/gallon or less.

At scale, those costs add up: The Utah Department of Transportation used 2.1m gallons of brine and 202k tons of salt in a recent winter — a total cost of ~$4.3m.

Spending a couple million is far cheaper than the alternative.

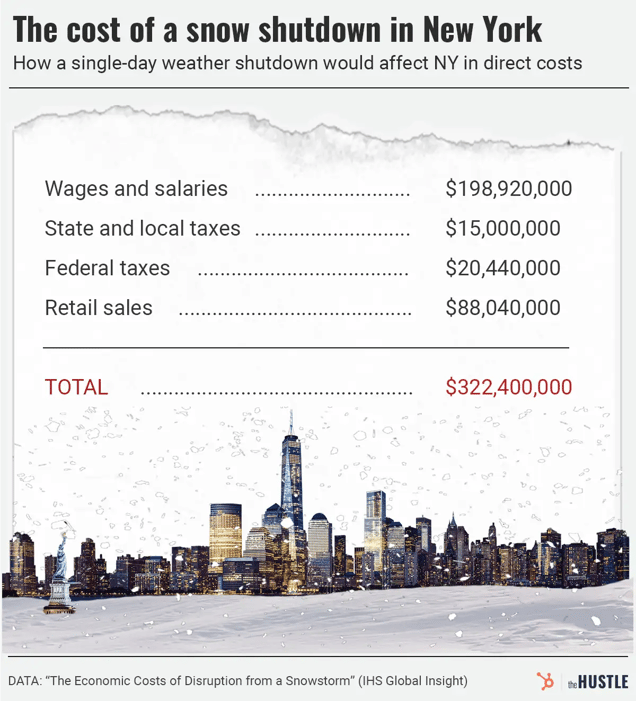

According to a 2014 study by IHS Global Insight, states can lose anywhere from $70m to $700m a day in lost wages, retail sales, and tax revenues when they’re shut down by winter weather.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Economists estimated the Texas winter freeze of 2021 cost anywhere from $150B to $300B, although much of that was attributed to widespread power shortages that could have been avoided with comparably minimal investment.

The human toll can be worse:

- As many as 700 people may have died during the Texas winter storm.

- When a bomb cyclone struck the US last month, dozens died in Buffalo, New York, as emergency responders struggled to traverse roads.

Given the potentially catastrophic consequences, stocking up on plows, salt brine, and labor would seem like a no-brainer. But not for every city.

The complications of planning for winter

Cities and states use average weather patterns to estimate necessary expenditures for a given year. But the costs of snow — like the weather — are often unpredictable.

“A budget is a guess,” says Luke Reiner, director of the Wyoming Department of Transportation, which budgeted ~$30m for treating snow and ice this winter and expects to spend as much on labor, materials, and equipment.

When cities and states see a milder winter than average, they have sunk costs, including money owed on equipment, materials that may expire, and labor. They may also utilize a similar number of resources for one blizzard as they would for several average snow storms.

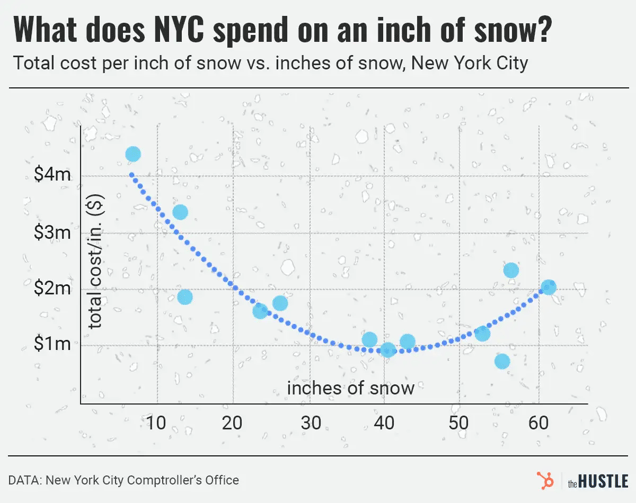

In 2007, New York City spent ~$45m on ~15 inches of snow, roughly the same amount it spent on ~40 inches of snow in 2005, the latter amount being closer to its annual snowfall average.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Above-average snowfall entails greater hits to the budget:

- Overtime pay and extra fuel for plow drivers

- Overtime for law enforcement officials

- Extra de-icing materials, which have become more expensive and harder to attain in the middle of winter because of salt shortages in recent years

- Payments for contracted workers and equipment

The Wyoming Department of Transportation went ~$10m over budget in the winter of 2019-20. Boston, which saw ~110 inches of snow in 2014-15, spent $40m — more than 2x its $18m budget.

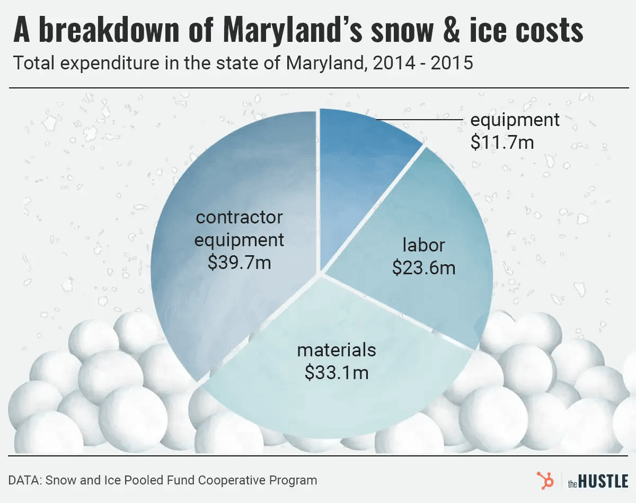

Maryland saw ~67% more winter storm events than usual in 2014-15 and spent $108m.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

After severe winters, roads are often rife with cracks and potholes — and not just because of the weather damage. State agencies typically run on a net-zero budget. Extra amounts spent on snow must be taken from somewhere else, usually by delaying summer construction projects and repairs.

The Wyoming Department of Transportation doesn’t hesitate to reallocate money during severe winters, seeing snow removal as a “no-fail mission” that supersedes its other duties, according to Reiner.

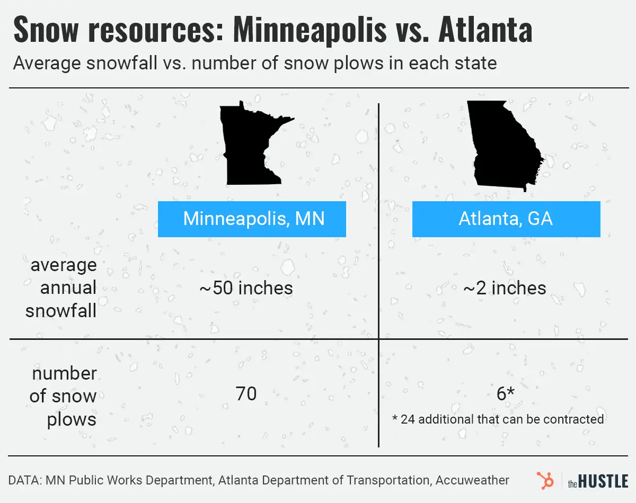

The same is true for Minneapolis, which sees ~50 inches per year and budgets $13m annually for snow removal.

- The city uses a fleet of dozens of plows and full-time and part-time staff.

- Its Public Works Department works around-the-clock shifts during snow emergencies, first clearing primary roads needed for people experiencing emergencies and who need to get to work.

- After heavy snowfalls (~12-18 inches), the Public Works Department can return Minneapolis to regular levels of activity within three days.

“To be a winter city and to have an enjoyable experience, you really need this sort of budget and support,” Margaret Anderson Kelliher, director of the Minneapolis Public Works Department, says.

The economic calculus is trickier for cities and states in the Sunbelt.

Atlanta has far less equipment and trains workers who have a variety of roles to clean up snow. The city rarely clears smaller neighborhood roads as temperatures usually rise above freezing after a couple days.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

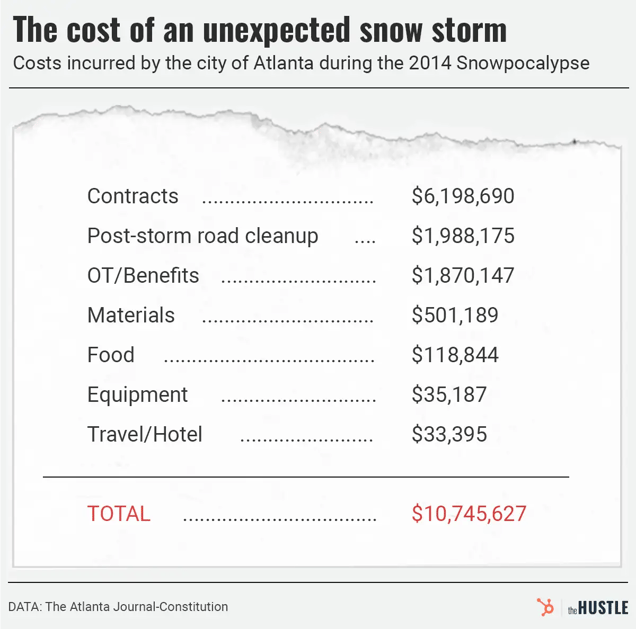

But every so often a winter storm leaves Atlanta vulnerable.

The infamous Snowpocalypse of January 2014 stranded thousands of people on Atlanta-area roads after two-plus inches of snow. That storm cost Atlanta $2.8m.

When a severe ice storm hit the city again two weeks later, the city’s reaction was swifter, albeit more expensive, with most of the $10.7m cost going toward contracted workers and companies that assisted the city.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Since then, Atlanta has reevaluated its protocols for when to announce weather emergencies and attempted to better educate local drivers on the dangers of ice and snow. The city hasn’t made major investments in equipment or materials that might expedite snow removal or lower the cost of cleaning up a severe winter storm.

“If I told the community we won’t pave any more roads because we’ll stockpile salt and buy more plows, I think there would be a very unhappy community,” Marsha Anderson Bomar, interim commissioner of the Atlanta Department of Transportation, says.

“They want us to prioritize things that matter most of the time and manage the more rare occurrences.”

Coming this winter: A labor shortage

Even some of the most heavily funded states and cities will be unable to achieve an ideal level of investment in snow cleanup this year: supply chain issues have complicated procurement of salt and de-icing materials, and plow drivers are difficult to hire.

A survey by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials last February indicated 84% of city and state agencies responsible for snow cleanup had higher-than-normal driver vacancies.

- Many drivers have stopped working and potential drivers have not entered the field because of low wages, especially for the difficult work involved.

- Many states need drivers in remote areas where few people desire to live.

The Wyoming Department of Transportation budgets for 450 drivers but was ~67 drivers short as of early December.

WYDOT has explored offering free housing to drivers who have been priced out of areas like Jackson Hole, and the state bumped up the hourly wage for a driver to $18.14, from $17.31, which Reiner acknowledges is still not enough.

Snow plow drivers are in short supply in some states (Getty Images)

The agency can mitigate its shortage by transferring drivers across the state to areas facing greater impacts from winter storms. But statewide storms will be a problem.

“If there’s a statewide storm, we have said publicly the response will be slower,” Reiner says. “There’s fewer plow trucks on the road.”

And when there aren’t enough drivers, supplies, or plows, the effects can be far-reaching. Just ask one-time Chicago Mayor Michael A. Bilandic, who knew that his fate was sealed by the blizzard of 1979.

“In the end, God sent us 100 inches of snow,” Bilandic said years later. “And I happened to lose [an] election because of it.”