One day last October in the southwestern Ukrainian city where Olena Hryhorenko lives, the lights went out. Her house lost access to electricity, water, and the internet. The streets turned pitch-black.

In the darkness, she reached for a flashlight and started to knit.

The blackout, caused by Russian attacks on Ukrainian power systems, lasted two days in Hryhorenko’s city of Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi and set the tone for a brutal winter of energy rationing and rolling blackouts. Over the next several months, Hryhorenko had electricity and water for four to six hours a day. At night, her family continued to dedicate limited battery power so Hryhorenko could practice her craft by flashlight.

Hryhorenko, who is 19 and a university student, has knitted since she was 12 and started an Etsy shop called Toysknit in 2018, selling knitted deers, squirrels, and bunnies in Easter and Christmas garb.

The cold, dark months were a challenge, but Hryhorenko managed to keep her business afloat and ship orders on time. In the last year, she’s sold 100+ knitted figurines to buyers across the world, using the money to help support her family.

Across Ukraine, there are thousands of crafters like Hryhorenko. For years, they’ve turned traditional hobbies into side hustles and full-fledged businesses, developing an outsized presence on the popular online marketplace. Per capita, Ukraine has more Etsy items for sale than every large European country except the United Kingdom and Germany.

It’s a skill that’s become a lifeline over the last 19 months. During the war, selling on Etsy and other digital platforms has been one of the surest ways to make money in an economy ravaged by war. For some Ukrainians, at times it’s been the only way.

Crafting as an economic engine

Hryhorenko’s mother knitted. So did her grandmother. And so did her great-grandmother, who made yarn from sheep raised by the family.

“I would say it’s our family talent,” says Hryhorenko, who, like most Ukrainians featured in this story, spoke to The Hustle over direct messages or email.

Olena Hryhorenko has made knit figurines for her Etsy shop Toysknit since 2018. (Via Olena Hryhorenko)

Knitting and embroidery (along with jewelry-making and woodcarving) are pastimes for the entire country.

Ukrainians trace their craft industry back to at least the 13th century, when it helped bring distinct regions together in trade. As the area was controlled by the Soviet Union, Ukrainians relied on their DIY skills to design clothing, make gifts, and cobble shoes. It was one of the few ways to obtain — and maintain — quality goods.

“That kind of innovation and craftiness comes from a lack — when it’s not easy to buy everything you need,” says Laada Bilaniuk, an anthropology professor at the University of Washington who is of Ukrainian descent and studies Ukrainian culture and society.

Since the country gained independence in 1991, residents have brought their work to a broader audience. Ukrainians sell their wares everywhere from local markets and malls to designer stores. (In 2016, Vogue hailed Ukraine as the fashion capital of knitwear.) Many businesses also sell on Etsy.

- Despite having a smaller population than Spain or Italy, Ukrainian sellers have nearly double the number of Etsy listings. They also have more listings, per-capita, than France.

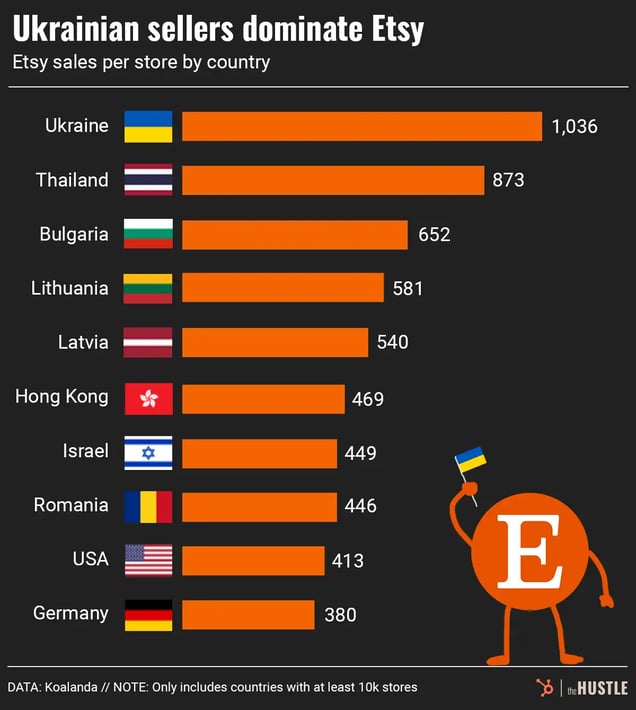

- As of late September, Ukraine had the highest sales-per-store average in the world among countries with at least 10k stores, according to data compiled by the Etsy data tracker website Koalanda. The average Ukrainian store sells more than 2x as many items as the average US store.

“It’s hard to imagine any Ukrainian family without at least one embroidery or knitting lover,” says Anton Gladkov, who runs the store WonderlandUkraine. “Over the years of [having a store on] Etsy, I realized that this is really much more developed in our country than in any other country in the world. That is why our products are in demand in the West.”

The Hustle

There are economic reasons, too.

The country’s economy grew slowly after independence and was battered by corruption, the Great Recession, and Russia’s invasion of Crimea in 2014. Although opportunities increased in recent years before the war, spurred by the information technology sector, finding good jobs has been harder for young people without university degrees, particularly in smaller cities.

In a town of 30k outside of the city of Poltava, Oksana Safronova couldn’t get a job in her field as an accountant, so she worked as a supermarket cashier. She started an Etsy store, Beadbox Boutique, in 2016, making ~$3.5k per year from selling her own crocheted jewelry and decorations.

The pay is better than her cashier job and the flexibility of Etsy also gives her more control over life. It also provides an outlet — one that she and others have needed more than ever during the last 19 months.

“Creativity,” she says, “gives strength to live on.”

Running a business amid war

On February 24, 2022, Magdalina Felk woke up to explosions. She was in Kharkiv, where Russia fired missiles in one of its first assaults on Ukraine.

“[I remember] asking my husband, ‘What’s happening?’” she recalls. “He said, ‘War has begun.’”

Felk’s family stayed in the basement for days. They lost power during airstrikes. Soon, Felk, her husband, and her two children moved out of Kharkiv to a safer region. She was among millions to migrate within Ukraine. Another ~6m have left the country.

Magdalina Felk, who runs the Etsy shop CrochetHappinessUA, with her husband and two children. (Via Magdalina Felk)

Even those spared the worst of the violence have felt the war’s economic unrest.

- Ukraine’s GDP fell by 29% in 2022, compared to the previous year. (It’s expected to recover this year, growing by ~3%.)

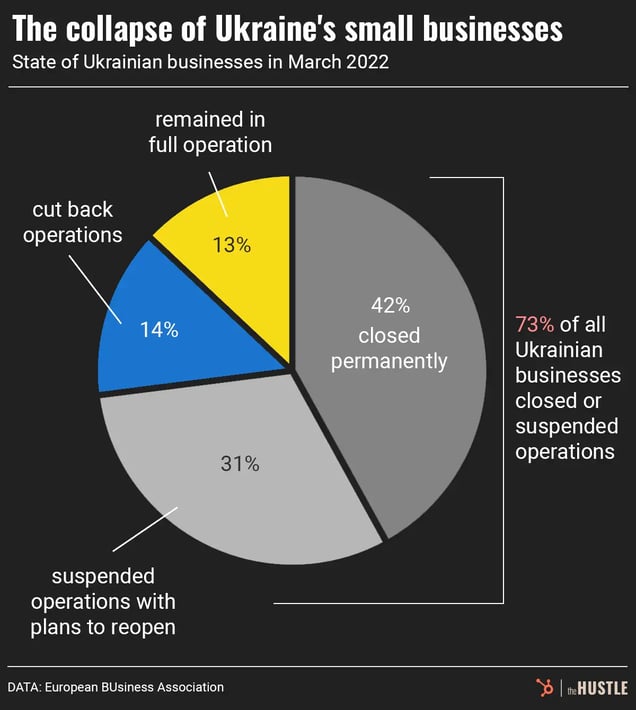

- In the weeks after the war began, 42% of small businesses ceased operations. The country’s top exports, sunflower oil and grains, essentially fell to zero in the month after the war began. There was barely any gasoline and store shelves were bare.

Felk’s husband lost his manufacturing job. The plant where he worked was destroyed by a missile, she said. For several months, their lone source of income was her Etsy store, CrochetHappinessUA.

She started crafting about five years ago. When Felk was on maternity leave, she wanted to make a homemade toy for her child and taught herself to knit, becoming proficient enough to crochet toys for friends and eventually for customers on Etsy. Now, aside from savings, the store was all they had.

“We lived only on my orders from Etsy,” she says.

The Hustle

Still, in the war’s early days, staying open on Etsy was also a challenge.

The postal system shuttered in February and March 2022, making it impossible for Ukrainians to ship goods or order materials. According to Koalanda, the number of Ukrainian shops declined to ~24k from ~36k, within three weeks of the onset of war. Those that stayed open depended on donations from friendly customers or pivoted to selling digital goods.

Gladkov’s craft supply shop, WonderlandUkraine, switched to selling digital embroidered images customers could print out. Once the postal service reopened, he couldn’t offer as many craft supplies because many manufacturers had reduced their output or moved abroad, as had some of his store’s employees. The cost of supplies went up, and domestic consumer demand went down.

By spring 2023, WonderlandUkraine had partially recovered, making most of its physical goods available again, alongside the new digital items.

But Gladkov says changes to Etsy’s algorithm caused Ukrainian digital products to lose favored positions they’d held in search in the weeks after Russia invaded, and his shop doesn’t make enough money to recoup its investment in their development. (Etsy, which launched a page dedicated to supporting Ukrainian merchants and canceled $4m in fees owed by Ukraine sellers, did not respond to an interview request.)

Zhanna Shostak runs the Etsy jewelry shop FamiliaFamilicomua. “Ukrainian women love to be beautiful,” she says. “Therefore, they bring beauty to others.” (Via Zhanna Shostak)

Another store, InsideOutGift, which sells embroidered sweatshirts, blouses, and apparel, averaged 20-40 sales per day before the war, mostly to Americans. The number dropped to between zero and one per day last year.

While many customers sent donations and messages of support, Oksana Ostroushko, who runs marketing for the shop, says others were discouraged by the prospect of longer shipping times.

Regaining success has been tough for Inside Out. Ostroushko says the war-induced sales decline puts them at a disadvantage because Etsy’s algorithm reduces the prominence of stores with lower sales.

The store now averages three to five sales per day, with the slowdown on Etsy making Inside Out more reliant on its Ukrainian Instagram page and brick-and-mortar locations in Kiev malls.

The store, however, did find a new revenue stream in the war: selling gear with patriotic Ukraine designs.

“Because of that decision,” Ostroushko says, “our business is still alive.”

The fear of losing everything

On a Sunday in late September, Ostroushko awoke to air-raid sirens in the middle of the night. She and her boyfriend, who live on the eighth floor of an apartment building in the Odesa region, hurried downstairs, watching a Ukrainian weapon ward off a Russian drone attack in the sky. They stayed on the first floor until it was safe to return upstairs.

More than 18 months into the war, the experience wasn’t unusual. The sirens go off several times a week in Odesa.

“We’re used to living in these circumstances,” Ostroushko says.

In the light of day, she tries to find a semblance of routine: hanging out with friends and family. Playing sports. Working to support herself and to give a portion of income to the war effort.

A family in Lviv, Ukraine, celebrates Orthodox Christmas Eve during a power outage. (Artur Widak/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images)

But life in a war zone will never be normal.

Hryhorenko says she’s had to adapt to a new reality and is not optimistic the war will end soon. She believes morale is getting worse as Ukrainians struggle from depressed wages, fear for their children’s future, and cope with the constant fear that they could lose everything.

In this harrowing time, she’s thankful she can knit. When Hryhorenko relaunched her store not long after the start of the war, skeptical anyone would want to deal with long shipping times and other potential complications, she wasn’t sure she would even have that. Within two hours, somebody purchased a pair of knit bunnies.

The moment offered her a feeling she feared the war had taken away: inspiration.