Take a look at any given corporation’s registration docs, and there’s a good shot you’ll see the address 1209 North Orange Street.

Spanning less than a city block in Wilmington, Delaware, this nondescript office building is the official incorporation address of 285k+ companies from all over the world.

On the surface, there’s no reason that Delaware — home to blue hens and Civil War monuments — should be a corporate paradise. It’s the second smallest state in America, and the 6th least populous, with just 986k residents.

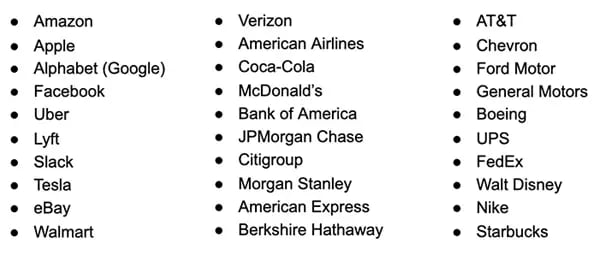

Yet, nearly 1.5m businesses from all over the world are incorporated there, including 68% of all Fortune 500 firms. Among them:

How did Delaware become an unlikely mecca for corporate America? And why are so many businesses parked there?

The story begins 100+ years ago, in New Jersey

In the early 19th century, every company had to be incorporated (legally established) in the state where they conducted business — and beholden to that state’s tax codes.

Post-Industrialization, huge firms like Standard Oil and the Whiskey Trust began to consolidate fractured markets. To combat this, many states set up laws aimed at regulating monopolies through heavy taxation.

But New Jersey saw an opportunity to cater to industry.

In 1891, the Garden State adopted an extremely generous corporate tax law that “would allow business to do as business pleases.” By incorporating there, a company based in another state could save big on taxes and enjoy perks like unlimited market expansion.

A flood of conglomerates took up this offer and New Jersey earned so much from taxes that it was able to pay off its entire state debt.

Pressured to incentivize businesses to stay, other states offered their own lenient corporate tax policies.

In this so-called “race to the bottom,” Delaware emerged victorious.

Adopted in 1899, the Delaware General Corporation Law “reduced restrictions upon corporate action to a minimum” and promised to maintain the most hospitable business enclave in the nation — a place where corporations could frolic in the open fields of capitalism, unencumbered by income tax, bureaucratic policing, and shareholder litigation.

A copy of Delaware’s Corporation Law of 1899 (Widener University, Delaware Law School)

In the ensuing decades, many other states (including New Jersey) reneged a bit on their corporate leniency.

But Delaware didn’t peel back.

Today, the state is still the incorporation zone of choice for corporations. The climate is so favorable that even international firms seek respite there.

What exactly makes Delaware so enticing?

The Delaware loophole

Let’s say you run a tennis ball company in California that rakes in $100m/year in net income.

In California, you’ll pay a state income tax (8.84% of net income) — and possibly an alternative minimum tax (6.65%) — in addition to the federal corporate tax rate of 21%.

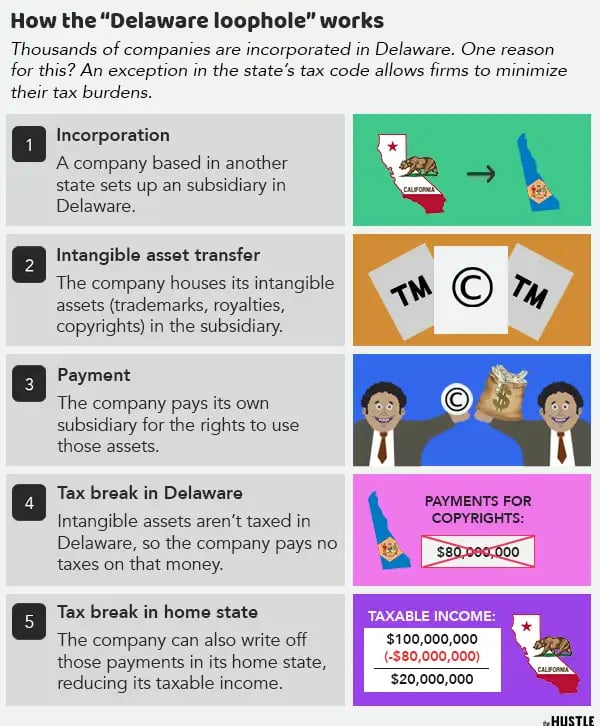

By incorporating in Delaware, though, you can likely save millions in taxes with something called the “Delaware loophole.”

In Delaware, intangible assets — think trademarks, copyrights, and leases — are free from taxation. Companies will often transfer these assets to a Delaware subsidiary and pay their own subsidiary for the rights to use said assets. This saves them money on both ends:

- The company can write off these payments in its home state, dramatically lowering its tax bill.

- The company isn’t taxed on its dealings in Delaware.

So, if you pay your Delaware subsidiary — let’s call it “Tennis Ballz, LLC” — $80m for the rights to use your own copyrights, you could potentially cut your taxable income down from $100m to $20m, saving you millions in taxes.

As any Delaware tax attorney will attest to, the system is a bit more complex than this. But the process can generally be simplified as such:

The most famous real-life example of this comes courtesy of Toys “R” Us.

Twenty years ago, the national chain formed a Delaware subsidiary — Geoffrey LLC — and paid the subsidiary an annual fee for the rights to use its own name and mascot. In 1990 alone, these payments allowed them to skirt around $2.8m ($5.5m today) in South Carolina state taxes.

Incorporating in Delaware comes with a slew of other tax perks, including:

- No state corporate income tax

- No sales tax

- No tax on interest/other investment income

- No value-added taxes

- No personal property tax

- No inheritance tax

Instead, all a business pays is a franchise tax ($175-$180k, depending on size) and small agent, annual report, and registration fees.

For the state of Delaware, these small fees add up to as much as 41% of the state’s entire revenue. In 2019, they collectively amounted to $1.4B.

For other states, the deal isn’t so sweet: It has been estimated that the Delaware loophole costs other states as much as $9.5B per year in collective lost tax revenue.

But taxes aren’t the main benefit of incorporating in Delaware: Most businesses are in it for privacy and courts.

Corporate privacy and expediency

When a company wants to incorporate in Delaware, it works through a registered agent — a person in the state who acts as a middleman, collecting paperwork and providing the company with a physical address.

In Delaware, there are 2 huge registered agent firms:

- CT Corporation (1209 Orange Street) is home to 285k+ businesses, including Walmart, Apple, and Coca-Cola.

- CSC (2711 Centerville Road) houses firms like McDonald’s, Amazon, and Facebook.

This nondescript office building at 1209 North Orange Street in Wilmington, Delaware, is the address of ~300k corporations from all over the world — but none of them are actually based here. (Wikipedia)

In Delaware, the incorporation process can take less than one hour to complete — and the state doesn’t require companies to disclose the names of officers and directors, allowing for anonymity.

“Delaware is the state that requires the least amount of information,” a business registration agent in Delaware told The New York Times in 2012. “Basically, it requires none. Delaware has the most secret companies in the world and the easiest to form.”

Carl Levin, a retired senator from Michigan, has said that it’s easier to set up a corporation in Delaware than obtain a driver’s license.

This expediency, coupled with the allure of anonymity, has attracted a slew of shady enterprises to Delaware in recent years:

- Viktor Bout, a Russian arms dealer once known as “the merchant of death,” had nearly a dozen Delaware shell companies.

- Tim Durham used a Delaware shell company to run a $207m Ponzi scheme on more than 5k elderly Americans.

- Carl Ferrer used a Delaware shell company to house the sex trafficking website Backpage.com.

- El Chapo used a Delaware LLC to hide cartel drug money.

Of course, the vast majority of Delaware corporations and LLCs are legit enterprises. And for these firms, the courts are a major draw.

A favorable court system

Delaware has what is called a Court of Chancery.

Here, corporate lawsuits are resolved by the court’s judges — who specialize in corporate law — rather than juries. While the average civil trial in America can take 2-3 years to resolve, Delaware’s process is far more expedient.

The judicial officers of Delaware’s Court of Chancery oversee the state’s business-related litigation (Delaware.gov)

As Priceonomics reported, the Court of Chancery’s former head judge once famously said: “If you need an answer in four days, you’ll get an answer in four days. [Delaware’s] Supreme Court will turn heaven and earth itself to give you an appellate answer.”

Many legal experts claim that these courts are overwhelmingly favorable to corporations — particularly when it comes to shareholder disputes.

Bigger picture

Despite its favorable climate, Delaware’s status as a domestic tax haven is widely debated.

But there is no denying that the state is part of a broader trend that has seen the US shift away from financial transparency in recent decades.

According to the Tax Justice Network, an advocacy group that tracks tax avoidance, the US is now the second-largest tax haven in the world, trailing only the Cayman Islands.

American’s so-called “wealth defense” industry — a system rife with shell companies, secret cash caches, and tax avoidance mechanisms — has widened the nation’s income inequality gap.

Efforts to rectify this are underway.

A new federal law passed in late 2020 banned anonymous shell companies in the US. But the full picture of how this might affect Delaware remains unclear.

In the meantime, you’ve got 68% of the Fortune 500’s mailing address if you’d like to voice your concerns.