If you file your taxes through TurboTax or a similar online service, you’ve likely seen a certain question during your annual return: “Did you perform work in more than one state?”

Given that this is the 21st century, there’s a decent chance you did. You might have responded to several emails from your boss during a long weekend in Denver or spent a day on Zoom before skiing in the Poconos.

But a state’s department of revenue is unlikely to notice that you visited, or that you completed any work.

Unless you’re a professional athlete.

When football players for the Jacksonville Jaguars, who owe no income tax in their home state of Florida, traveled to Kansas City last week for a playoff game with the Chiefs, they accumulated an income tax bill for both Kansas City and the state of Missouri. The Dallas Cowboys players who visited Santa Clara to play the 49ers drew a bill from California.

This burden is known as the jock tax. Professional athletes owe a portion of their salary to most states and cities they visit — even for a single day.

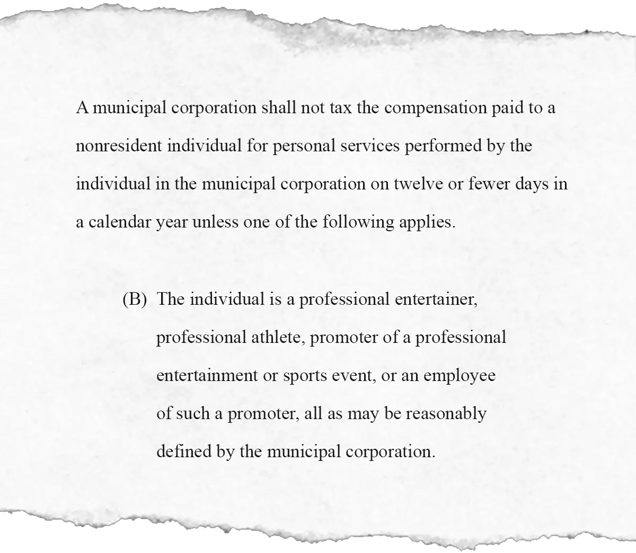

Legal text via Hillenmeyer v. Cleveland Bd. of Rev., p.10; 2015

Unlike, say, nurse practitioners or graphic designers, jurisdictions know exactly when athletes are in town. They know how much they make. And they know how to go after them.

For years, the jock tax has flown under the radar, known mostly to hardcore sports fans and accountants. Nobody, after all, really cares if millionaires have to file complicated tax returns.

But the jock tax matters.

Hardly anyone truly benefits from the tax, and one day in the future, even if you’re not an athlete, you may have to pay it.

Michael Jordan’s Revenge

In 1991, hardly anyone had heard of a jock tax, including John Cullerton, a freshman state senator in Illinois.

That June, Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls defeated the Los Angeles Lakers in the NBA Finals five games, three of which were played at the Great Western Forum in Inglewood. Based on media reports at the time, California charged Jordan ~$10k in taxes for his three nights of work.

The concept wasn’t new: California had been levying taxes on visiting athletes since at least the mid-1980s and netted ~$2.5m in 1990 alone. Wisconsin and Ohio had jock taxes, too.

Cullerton doesn’t remember exactly how he heard about the jock tax — perhaps he read a news story about the Bulls’ California taxes — but he was inspired to make a “defensive move.”

“If they’re taxing Michael Jordan,” Cullerton told The Hustle, “but we’re not taxing Magic Johnson, it’s not fair.”

That summer, Illinois passed a bill that taxed visiting athletes, only if those athletes hailed from a state that also had a jock tax. The law, which garnered publicity, was dubbed “Michael Jordan’s Revenge.”

An onslaught of jock taxes followed over the next few years.

Today, every state with a pro sports franchise that charges a state income tax has a jock tax. The taxes proliferated for several reasons:

- Many states were facing spiraling deficits and attempted “boutique government” strategies to earn revenue, instead of raising taxes on the majority of residents.

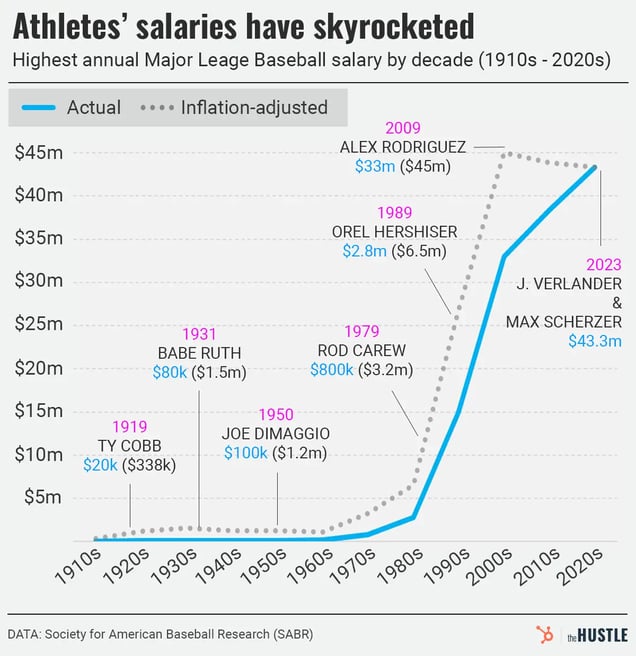

- Salaries for professional athletes were escalating, making them bigger targets.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Cities wanted in, too:

- Philadelphia enacted a jock tax in 1992, seeking back taxes for the past two years and, in the words of a city solicitor, going after anyone “tangentially connected to the game.”

- Detroit officials served bench warrants on delinquent players for the New York Yankees and Toronto Blue Jays.

Athletes were soon filing 10 to 15 tax returns every year. As superagent Leigh Steinberg noted in the early ’90s, the jock tax was “an accounting nightmare.”

How the jock tax works

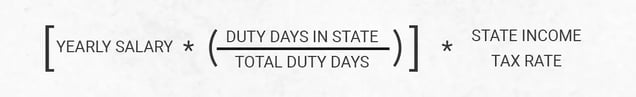

Despite the need for copious paperwork, the calculation for the jock tax is fairly simple.

Most jurisdictions use a formula known as duty days, which includes days spent practicing and playing games during the season, as well as certain offseason activities. The duty day count ranges from 150+ for the NFL to 180+ for Major League Baseball.

States calculate the amount a visiting athlete earns by multiplying an athlete’s annual salary by the number of duty days an athlete practices or plays in their jurisdiction divided by the total number of duty days. That number is then multiplied by a state’s personal income tax rate:

To make the process easier, teams typically withhold and remit athletes’ wages to various states and cities throughout the year.

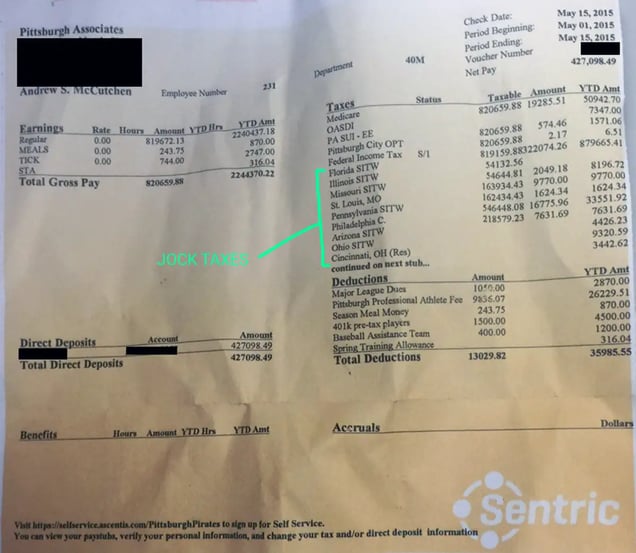

With athletes making several road trips every month, the jock tax can lead to lengthy paychecks, as a leaked pay stub from baseball star Andrew McCutcheon revealed.

Via Reddit used Grassiii, who found the paystub in the visiting locker room during a visit to Chicago’s Wrigley Field

Over the years, some states and cities have pushed the limits of the jock tax, running into constitutional issues:

- Starting in 2009, Tennessee charged a flat tax of $2.5k per game to visiting NHL and NBA players to fund improvements to arenas. For NBA players making the league minimum at the time, $458k annually, the tax exceeded the amount they made for a day of work. The tax was repealed in 2014.

- Cleveland calculated its jock tax based on games played rather than duty days, leading to athletes paying a disproportionately high tax bill to the city.

The Cleveland tax had been on the books for years before Hunter Hillenmeyer, a former Chicago Bears linebacker, realized he owed the city ~$5k for a single preseason game during a week he made ~$1.1k. Hillenmeyer and fellow NFL player Jeff Saturday won a lawsuit against Cleveland in 2015, forcing the city to reform its jock tax.

“It feels crazy,” Hillenmeyer told The Hustle, “that it took a lowly athlete that doesn’t work in accounting to spot that and be like ‘huh?’”

Who benefits from the jock tax?

Perhaps the strangest thing about the jock tax is trying to figure out who wins. The answer is almost nobody.

Athletes, even when they travel to states with no income tax, still owe money to their home state for that work, so they don’t get any savings.

“If you’re a resident of the state, no matter what, 100% is taxable in the resident state,” said Jonathan Nehring, an attorney who operated the website TaxaBall.com.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

Most states don’t benefit either.

To ensure athletes are not double taxed, they provide credits for the jock taxes their resident athletes pay in other states, up to the amount their resident athletes would have been taxed had that “duty day” been at home.

- Because sports franchises typically play an equal number of home and away games, most states collect roughly as much money as they would have collected if jock taxes didn’t exist.

- One critic explained this phenomenon as “stealing from one pocket to pay into another pocket.”

Imagine, for instance, a two-game basketball series between the Phoenix Suns and Detroit Pistons. One day is spent in Arizona (which has a 4.5% income tax rate for high earners), and one day is spent in Michigan (a 4.25% rate). Let’s say the taxable income comes out to $1m for each team for each game.

- For the day in Detroit, Michigan would collect 4.25% of each team’s $1m, which is $85k. Arizona would also collect 0.25% of the Suns’ $1m because it would only credit 4.25% of the income earned in Michigan. That comes to $2.5k.

- For the day in Phoenix, Arizona would collect 4.5% of each team’s $1m: $90k. Michigan would collect nothing because the Pistons players would be taxed beyond what they would have owed their home state.

- That leaves Michigan with $85k and Arizona with $92.5k.

In a world without jock taxes, Michigan and Arizona would have simply charged their resident athletes full taxes for both days at their own tax rates, leading to $85k for Michigan and $90k for Arizona (and far less compliance work).

“It is a wash, to an extent,” said John Karaffa, founder of ProSport CPA, an accounting firm that specializes in athletes.

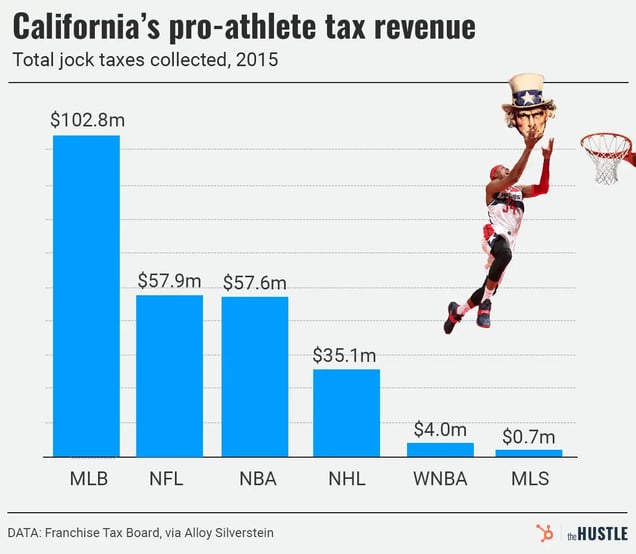

The exceptions are high-tax states like California, New York, and New Jersey, which all charge high-income earners more than 10%. They collect taxes from visiting athletes playing in their state and still collect a sizable portion of income from their resident athletes’ road games, after a credit, because their tax rates are so much higher.

- In a two-game series between the Golden State Warriors and Detroit Pistons, with the same conditions as above, California (which charges 13.3% for high earners) would collect $356.8k ($266k from the game in San Francisco and $90.8k from the amount the Warriors owe to California above what they paid Michigan).

- If jock taxes didn’t exist, California would have made $266k charging taxes on the Warriors for two days of work.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

States like California’s taxation essentially forces the hand of lower-tax states, which must levy a jock tax to collect roughly the same amount they’d collect in a world without jock taxes.

Michael Jordan’s Revenge, in other words, didn’t bring Illinois and similar states millions more in tax revenues. It just helped them compete in a game they can’t afford to quit.

“Unless all of [the states] ended it at the same time,” said Cullerton, the former Illinois senator, “it would be difficult [for a state] to unilaterally disarm.”

The connection to remote work

Sometimes, jock taxes aren’t just for jocks. They’re for everyone.

When Philadelphia began targeting athletes for a municipal tax in the 1990s, it also cracked down on doctors and lawyers who visited the city. Many states could do the same: Of the 41 states that charge income tax, around half require visitors to pay income tax if they work for a single day in the state. (Others have grace periods for several days or weeks.)

States have historically not bothered with average visitors. They track high-income earners with public schedules like athletes, “so they don’t have to focus on low-dollar-amount people,” according to Chris Cicalese, a CPA and associate partner at Alloy Silverstein.

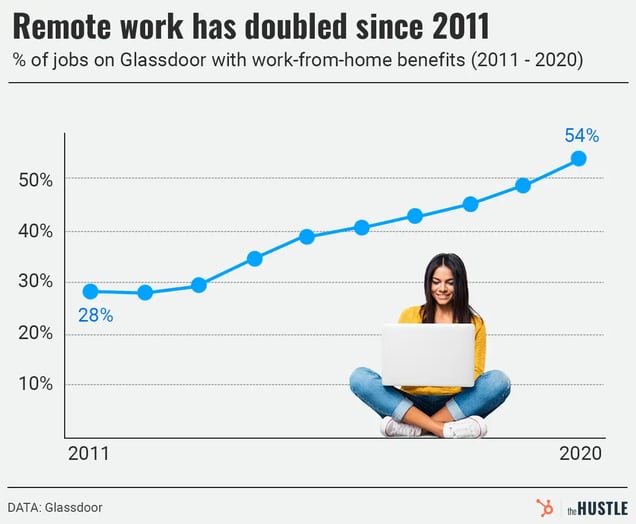

But that could change in the world of remote work.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

“There was a lot of grace given during the pandemic, but we’re past that now,” said Jared Walczak, vice president of state projects at the Tax Foundation. “States are getting more serious about this.”

- If states fear they’ve lost income taxes from big employers who let remote workers live in a different state, they may crack down on visiting remote workers, although it’s unlikely they’d go after people who spend a couple of days in a state, according to Walczak.

- The states could force big employers to track the locations of their remote employees and withhold taxes in the appropriate jurisdictions, as professional sports teams have done for decades. The employees would then have to file returns in the jurisdictions they visited.

To ward off this scenario, the Mobile Workforce Coalition and others have pushed for Congress to pass federal legislation that would create a 30-day grace period for a visiting worker in any state.

Despite bipartisan support, similar bills have stalled since at least 2012, although Walczak believes the idea could gain steam in the near future.

But a long wait could be troubling. As states have realized with the jock tax, once somebody starts playing, everybody joins in.