A few weeks ago, Ben Saul-Garner paid ~$3.7k to be abandoned on a remote island in Indonesia.

The 33-year-old entrepreneur flew from his home city of London to Jakarta, then boarded another flight to a regional airport. A car service drove him to a pier, where he climbed onto a janky speedboat and hummed across the ocean for 90 minutes until he reached an uninhabited mass of land covered in palm trees and dense brush.

The boat turned around and left, and Saul-Garner remained marooned there for 10 days, alone and nearly resourceless.

He slept in a hammock, subsisted on coconuts and crab, and spent his days foraging for firewood.

Ben Saul-Garner on his recent trip to an Indonesian island (via Instagram / @bsaulgarner)

“You actually realize just how much time you have in a day when you remove all distractions,” Saul-Garner told The Hustle. “There’s something about just being in nature and going back to basics that I love.”

The restless soul

Saul-Garner booked this experience with Docastaway, a company that caters to travelers looking for extreme isolation.

It was founded in 2010 by Alvaro Cerezo, a restless soul from Málaga, Spain.

Cerezo spent his summer days exploring the Alboran Sea’s rocky beaches and secret coves. By the age of eight, he was venturing offshore in an inflatable raft.

“I always dreamed about going beyond the horizon,” he told The Hustle. “And I knew that as soon as I had freedom, I’d see what was out there.”

Alvaro Cerezo gazing into the distance on one of the many desert islands he has ventured to (via Alvaro Cerezo)

The son of an engineer and a government administrator, Cerezo was encouraged to get an economics degree in college. But between his studies, he’d fly to Asia and pay a few bucks to hop on a fishing vessel bound for a remote island.

Islands became his obsession.

He began to develop an extensive knowledge of archipelagos in Indonesia, the Philippines, Polynesia, and Micronesia. After he graduated, he began to wonder if he could make a living out of his hobby.

“I wanted to do this every day of my life,” he said. “I had no idea if there were others out there who wanted to travel to these remote islands, but I decided to see.”

In 2010, Cerezo launched Docastaway (a combination of “do” and “castaway”) and billed his service as an escape from the clutter and digital chaos of the modern world. Travelers would pay Cerezo to dump them alone on an island, where they could spend time in complete and utter isolation.

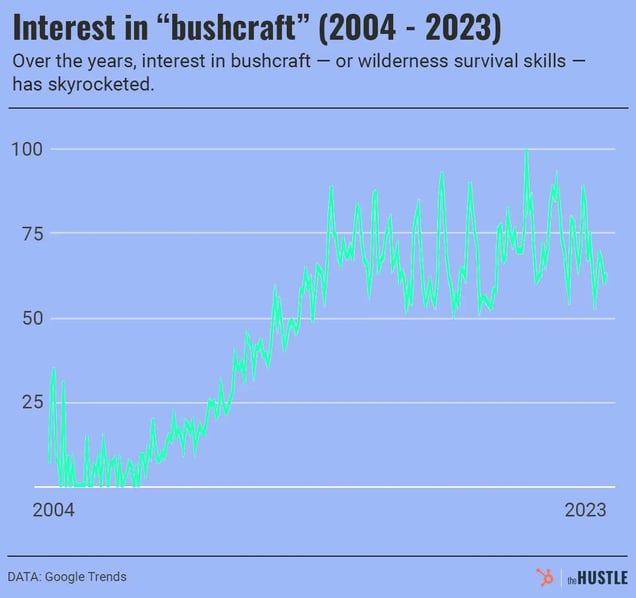

The timing for this service was fortuitous.

Interest in extreme wilderness tourism had taken off, thanks to TV shows like Man vs. Wild and Survivorman, and a growing number of YouTube channels dedicated to “bushcraft” — wilderness survival skills like foraging, building natural shelters, and starting fires.

People wanted to test themselves — and there was no better test than being marooned on an island without food, water, or shelter.

The Hustle

Cerezo’s first clients were his friends, whom he convinced to join him on a few “test” expeditions to his favorite remote desert islands. But eventually, adventurous travelers from around the globe began to organically discover Docastaway.

“There was no other company like this, so when people searched for ‘desert island company’ online, they’d find me,” he says. “The demand started to grow, and that’s when I really had to improve the experience.”

That meant finding the perfect islands.

The art of ‘finding’ an island

Cerezo realized early on that clients didn’t want to go too far to experience true isolation on a remote island. The typical customer only had around eight to 10 days budgeted for travel, and they didn’t want to spend more than two of them traveling.

“An island has to be remote and isolated — but not too remote and isolated,” Cerezo said.

Today, Cerezo has come to realize that bringing foreign tourists into remote island territories requires a fair bit of politicking, including payments and bribes. When he finds the perfect island, he flies out and meets with the island’s owner and local officials to work out arrangements.

“Bribes are important,” Cerezo says. “Everyone wants their piece.”

The typical process works like so:

- The island owner (either the government or a private owner) is paid $100-$150 for rental of the island for a few days

- Police are paid to prevent any issues like pirating or looting

- Local officials are paid to prevent fishing vessels and other boats from docking on the island when a client is there

Altogether, these bribes, tips, and payments typically amount to around $300 per trip.

“These aren’t Richard Branson types who own these islands,” Cerezo says. “Most of these islands have never seen a tourist. So, the owners are happy to accept any kind of payment they can get to authorize use for a few days.”

Approaching a remote island (via Alvaro Cerezo)

Providing clients with the illusion of complete solitude is harder than it sounds. Even on the most remote islands on earth, isolation has to be manufactured:

- Cerezo goes to great lengths to make sure local fishing boats don’t come into view of any island where a client is staying. This involves setting up a support team on a nearby island to “intercept” and pay off any boats that float too close.

- Before a client is taken ashore, the island also has to be cleaned of debris to give it an untouched appearance. (Islands in the middle of the ocean are often magnets for trash.)

Only one out of every 20 islands Cerezo surveys meets his criteria for safety and isolation.

The castaway experience

Today, Cerezo offers island experiences in Polynesia, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Central America. Prices range from €90 to €380 per night (~$95 to $400), and the typical trip is around a week.

Clients are responsible for their own flights to and from the destination, but once they touch ground, they’re shuttled to a nearby port and motored across the ocean on a speedboat — sometimes 90 minutes or longer — to live out their island fantasies.

Cerezo’s profit? “Very little,” he says. “I’m never going to get rich with this. I do it because it’s my passion. And it’s an excuse for me to continue exploring different islands.”

Fresh lobster, coconuts, anemone, and coral can be found in abundance on certain islands (via Alvaro Cerezo)

Over his 13 years in business, Cerezo has had over 1k clients. They range from entrepreneurs like Ben Saul-Garner, to students, to multimillionaires who are looking for a self-reliance test after years of indulging in luxury comforts.

When a client signs up, he or she has two options:

- “Survival” mode: They get dropped off on the island with barely anything (in some cases, just a machete or spear gun) and have to figure out everything on their own.

- “Comfort” mode: They have a crew on standby with food, water, shelter, and other necessities.

Survival mode has become an increasingly popular option in recent years.

Clients might elect to be left with a few items — a machete, a lighter, a speargun — but once Cerezo’s staff leaves the island, they’re on their own to forage for food, build shelter, and source water. Cerezo makes sure that the islands he selects have options.

Usually, this means catching fish and crabs and scaling trees for coconuts. Some clients even resort to eating things that get washed up on shore, like packaged goods and produce that fall off of local ships.

“Everything is very difficult on an island. You need to fight for everything you get,” said Cerezo. “I could be more romantic and tell you, ‘Oh yeah, this is the life.’ But it’s much better being in civilization. This is a true test for people.”

Clients who’ve gone on remote island expeditions with Docastaway (via Alvaro Cerezo)

Every client has to sign a disclaimer form accepting liability in the case of injury or death — though Cerezo says that hasn’t happened yet.

“They know it’s dangerous,” he says. “They’re alone with no hospitals. If you have to go to a hospital, it’s going to be at least four hours to get there. And even then, the hospitals we’re talking about are not very well equipped.”

Sometimes clients abandon ship early — usually due to extreme sunburn, sickness, fear, or even boredom.

“People go there thinking it’s going to be an Indiana Jones kind of adventure,” said Cerezo. “It’s not like that. A desert island is lonely. And some people can’t handle being completely alone.”

The isolation business

Docastaway isn’t the only desert island tourism outfit in town. UK-based Desert Island Survival offers a similar service geared toward groups.

“I was working in finance, and totally depressed,” the company’s founder, Tom Williams, told The Hustle. “I’d always felt like a square peg in a round hole. I wanted to see the untouched parts of earth, and go over the edge of the map.”

During an evening of despair, Williams came across Cerezo’s company and realized there was room in the market for another business.

Tom Williams stoking a fire on a remote island (via Tom Williams)

Williams’ service is less about transformative experiences and the poetry of isolation, and more about learning the skills necessary to survive in the wild.

“It’s about escaping the rat race, disconnecting, and learning how to survive in the real world,” he said.

Desert Island Survival is an eight-day experience — five days of hands-on training with one of the company’s survival skill experts, and three days of putting those skills to use in “survival mode” on the island. Clients learn how to:

- Build a shelter and make rope out of natural fibers

- Source water and food that doesn’t kill them

- Start fires using friction techniques like the “bow drill”

- Weave palms into baskets, hats, and beds

The expeditions are made up of groups of individuals — mostly solo travelers — who don’t know each other. But Williams will also occasionally cater to bachelor parties, father-son trips, and corporate retreats.

All in, the experience costs around £3k (~$3.7k) per person, and Williams says he’s done around 50 trips in total — 20 this year alone — with 60% margins.

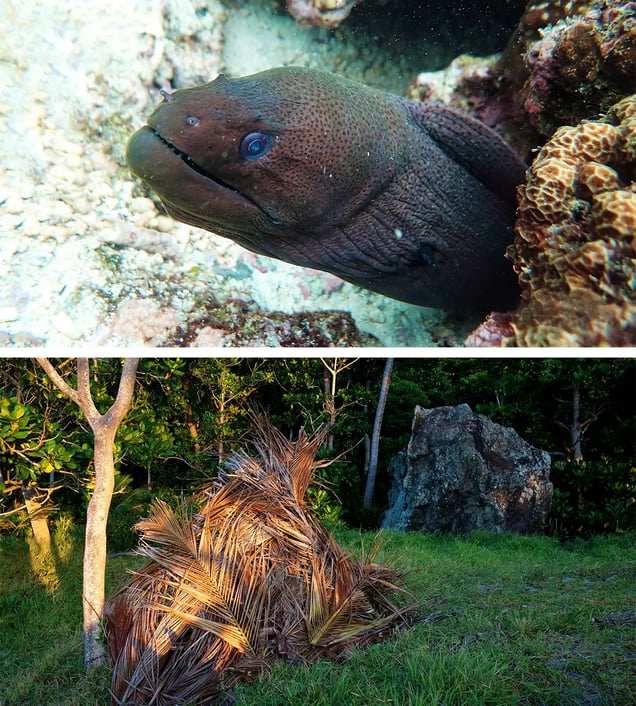

TOP: A moray eel; BOTTOM: A makeshift shelter (via Alvaro Cerezo)

Williams says his only bottleneck to growing the business is finding more islands.

“There are lots of beautiful islands in the Philippines, but there are pirates,” he said. “In Indonesia, there are pit vipers, and in New Guinea there are green mambas that can literally kill you.”

A “risks and dangers” tab on his website elaborates on the various traumas that can be inflicted by monitor lizards, wild pigs, sharks, jellyfish, pufferfish, stingrays, and other island-dwelling creatures.

He also has to contend with a formidable rival: reality TV shows.

When shows like Survivor and Naked and Afraid need a shooting location, they typically go for the same limited inventory of islands. And Williams says producers offer to pay handsome rental sums in excess of $100k. Recently, Williams says a very famous YouTuber paid $70k to rent an island in Panama for a video.

“He turned up there with friends, and there were way too many insects for them. So they left,” said Williams.

Williams often has to sign more relaxed contracts with islands that allow the owner to give him the boot if a more lucrative opportunity arises. He has backup islands nearby for any last-minute change of plans.

The last frontier

Both Cerezo and Williams are aware that the services they offer are up against the broader threat of wide-scale industrialization.

- Oceans are now acidifying faster than they have in 300m years.

- The waters are infested with trillions of plastic particles and large swaths of debris.

- Previously obscure islands are being privatized and developed at a rapid rate, often commanding millions of dollars.

An island sunset (via Alvaro Cerezo)

It’s getting harder to find any place — even a remote desert island — that isn’t unmarred by the hand of the modern world.

“We’ve had to drop a few islands from our service because they’re getting too polluted, or there are hotels being built there,” said Cerezo. “We will eventually need to go more and more remote.”

But Cerezo, now 43, is no stranger to a hard journey. He says he plans to be in the desert island business for the rest of his life.

“As long as I’m alive it will be there,” he said. “I want to make as many people as possible feel like the last person alive on earth.”