Last August, Alex Hernandez found herself in the market for a new piece of furniture.

Holed up in her Miami studio apartment, the 31-year-old executive assistant had grown weary of her “cheap and basic-looking” Ikea couch. She shopped around online and found a new one she liked — but it was a designer brand that was out of her price range.

So she opted for a makeover instead.

She spiced things up with a set of mid-century modern legs ($70) and a new cover ($120) from an Ikea customization website. The project cost Hernandez about one-tenth of the designer version she’d had her eye on and it saved an old piece of furniture from the landfill.

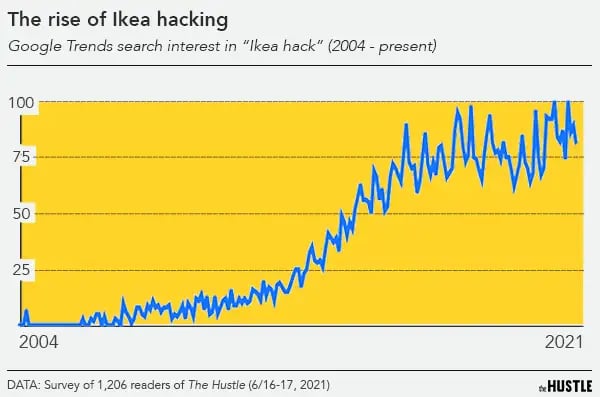

This type of upcycling, called Ikea hacking, has been on the rise during the pandemic.

And for companies that sell custom Ikea-friendly fixtures — legs, couch covers, knobs, and cabinet doors — business is booming.

What the heck is Ikea hacking?

Ikea has achieved the kind of scale and brand recognition that most companies can only dream of.

With ~$44B in annual revenue, 445 retail stores, and 217k employees, the Sweden-based company is the world’s largest home furnishings retailer, enjoying a stranglehold on the ready-to-assemble furniture market.

In many countries, 50%+ of the population owns at least one Ikea product.

The Hustle

In a way, Ikea is kind of like the Bitcoin of furniture: the company uses universal designs, meaning its hardware and measurements are uniform across most of the developed world.

And folks who want to add some pizzazz to their mass-produced Billy bookcases and Kallax shelf units have no shortage of customization options to choose from online.

Broadly, Ikea hacking is any form of upgrading, customizing, repurposing, or personalizing a piece of stock Ikea furniture.

The movement gained steam in the mid-2000s, when popular DIY blogs like Ikea Hackers and Instructables began offering up easy, affordable tweaks to popular items like Billy bookcases and Kallax shelf units.

At first, Ikea wasn’t a fan of people customizing its furniture and even sent Ikea Hackers a cease and desist. But since then, the company has embraced its hackers.

And over the past decade, this once small and wacky community has burgeoned into a full-fledged industry.

The Hustle

Nearly every social media platform abounds with Ikea hacking content:

- TikTok: 64m views on #ikeahacks videos

- Instagram: 500k posts tagged with #Ikeahack

- Facebook: hundreds of Ikea hacking groups with more than 1m collective members

- YouTube: thousands of Ikea hack videos with 100m+ views

- Pinterest: an endless scroll of DIY Ikea projects

- Reddit: r/Ikeahacks boasts 76k subscribers and has grown 400% in the past 5 years

Within this broader ecosystem, certain Ikea products have earned a cult following in niche communities.

Plant enthusiasts use Fabrikör cabinets to make their own indoor greenhouses. Photographers convert Schottis shades into DIY lightboxes. Parents transform Flisat tables into sensory stations for toddlers. Some have even crafted sex toys out of Ikea shoe trees and milk frothers.

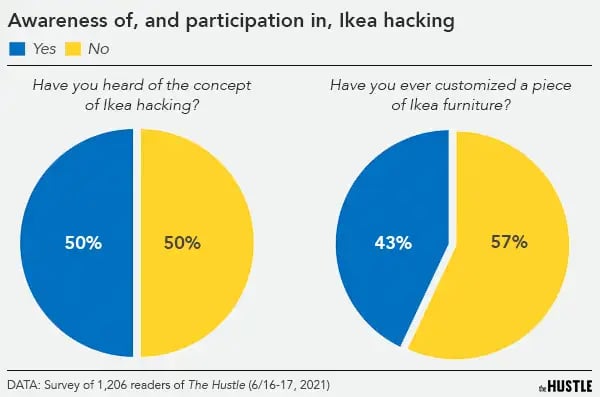

In a survey of 1,206 readers of The Hustle, half of all respondents said they had heard of the concept of Ikea hacking — and 43% said they’d engaged in the practice at some point.

The Hustle

In our survey, readers had no shortage of their own creative new uses for old Ikea furniture:

- Jordan Elgie (musician, Ontario) turned an Ikea shelf into an electric guitar pedalboard.

- Peter Sanderson (sales director, Rhode Island) converted an Ikea headboard into a dog gate for his Rottweiler puppy.

- Randy Hees (museum director, Colorado) built a floor-to-ceiling library using 26 Ikea bookcases.

- Rick Moore (film technician, Vancouver) transformed an Ikea butcher block cart into a wine rack.

- Laurel Choate (literary agent, New York) made a kitchen island out of Ikea shelves, legs, and a countertop.

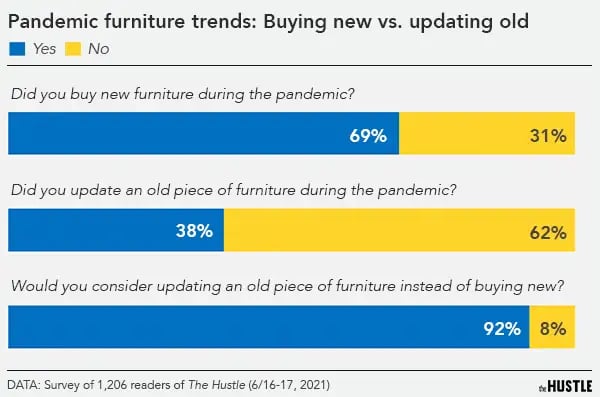

During the pandemic, an increase in remote work and time spent at home has led to a DIY remodel boom — and a surge in Ikea hacks.

Among our respondents, 69% said they had bought new furniture during the pandemic, and 38% said they had updated an existing piece of furniture.

The Hustle

“We disassembled a cheap Ikea table, painted it a new color, and bought new legs to make it more mid-century modern,” says Zoë Kronovet, a digital marketing manager in North Carolina. “We also bought a $300 velvet midnight-blue cover for a basic Ikea couch to give it a new life.”

Like Kronovet, the majority of Ikea hackers stick to simple aesthetic changes: new knobs on a dresser, a new set of legs on a table, or new cabinet doors — little touches to shake things up.

And they have no shortage of options to choose from.

The Ikea hacking industry

When on the hunt to revamp old Ikea wares, prospective customers often turn to a cottage industry of e-commerce startups — mostly female-owned — that specialize in Ikea customization:

- Semihandmade, Reform: customization options for Ikea kitchens

- Superfront, Norse Interiors: legs, hardware, and cabinet doors for an array of best-selling Ikea products

- Prettypegs: legs for Ikea sofas, tables, and consoles

- Kokeena: doors and casework for Ikea cabinets

- Panyl: vinyl wraps for Ikea furniture

- Bemz: covers for Ikea couches and chairs

On Etsy, you’ll find dozens of smaller companies hawking handmade legs, brass knobs, shelf inserts, and sofa covers specifically crafted to fit Ikea furniture lines.

A before/after kitchen remodel using an Ikea base system modified with Semihandmade mahogany panels (Semihandmade)

Monica Born quit her copywriting gig 10 years ago to found Superfront with her husband Mick, after noticing that many of her friends in Sweden were commissioning their own pricey Ikea replacement doors from local carpenters.

In Sweden, where 90% of residents own Ikea furniture, she sensed an opportunity to streamline and normalize the customization process.

Today, the business offers cabinet doors, handles, and legs compatible with Ikea’s 4 best-selling furniture lines.

Born says the company is on track to hit ~$8m in annual sales this year — a 50% bump from last year.

“It’s becoming more and more [common] to tell your dinner guests that you repurposed something,” she says. “It’s cool to say, ‘We thought it was crazy to throw away that piece of Ikea furniture so we redesigned it instead.’”

Jana Kagin left a career in psychology to launch the Stockholm-based Ikea customizer Prettypegs in 2012.

“Ikea is such a huge part of Sweden’s DNA — it’s in our breast milk,” she says. “But a lot of people want to differentiate from the mass-produced. We offer a more affordable option by pairing DIY with high-end design.”

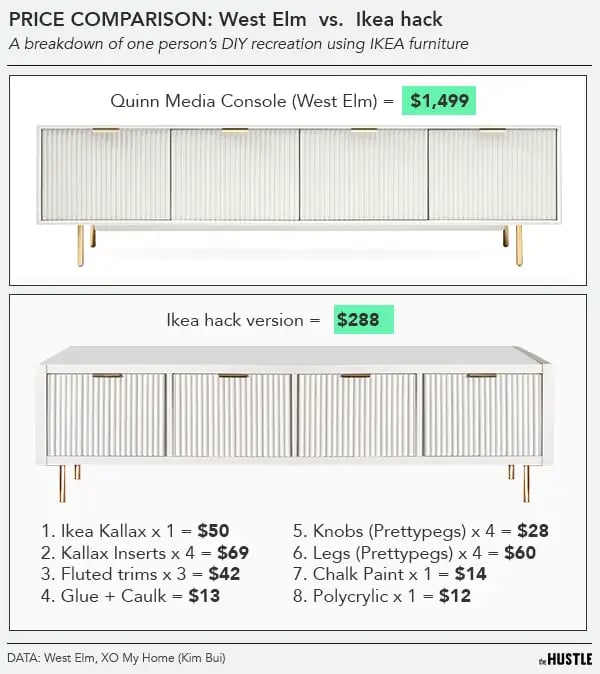

As an example, she cites a customer who was able to reconstruct a $1.5k West Elm console for $288 using a set of Prettypegs legs ($60), knobs ($28), and a bit of DIY handiwork.

Kim Bui, a Florida-based homeowner, hacked together a designer console replica using custom Ikea legs, hardware, and some elbow grease (XO My Home; graphic: The Hustle)

Demand is so high, she says, that it’s been hard to keep items in stock.

“When we first started, we thought, ‘It’s just furniture legs, it’s not rocket science!’ But everything becomes rocket science as a business scales,” she says. “Logistics, hardware, packaging, lacquer, paint — there are so many moving parts that have strained supply chains right now.”

While many of these companies are based in Sweden, some entrepreneurs have found success focusing on the US market.

Lotta Lundaas, the founder of Norse Interiors, based in New York City, says her company is on track to hit $1m in sales just 3 years after launching — a 3x increase year-over-year.

Lundaas leveraged her background as an online marketer to identify which Ikea products to offer custom cabinet doors for, reverse engineering the company’s best sellers by looking at search volume data.

Left: A stock Ikea Besta cabinet; Right: An Ikea Besta cabinet upgraded with cane double doors, chrome knobs, and chrome legs from Norse Interiors (Ikea, Norse Interiors)

The Copenhagen-based startup Reform has taken a different route.

Launched in 2014 with the aim of customizing Ikea kitchen cabinets, the company has since moved into offering its own product lines. But it has trouble keeping its prices appealing to the Ikea demographic.

“It’s hard to match Ikea’s economies of scale,” says Scott Bird, the company’s managing director. “They sell some of their products at a price that’s lower than what we can even source them for.”

But these economies of scale come with a price.

An antidote to ‘fast furniture’

Beyond design, Ikea hacking aims to tackle a larger problem: the scourge of so-called “fast furniture.”

In the 1950s, furniture was seen as a generational investment that would last decades. Today, the average couch lasts just 6 years. Each year, Americans discard 20m tons of furniture — a figure that has doubled in the last decade.

Ikea — a company that uses 1% of the world’s entire wood supply and has encouraged customers to frequently replace furniture in the past — is at the center of this problem.

Part of the stated mission of Ikea hacking, and the upcycling movement at large, is to extend the lifespan of furniture.

In its own independent research, Prettypegs found that a simple design change could result in a person keeping a piece of furniture 20% longer. The company estimates that it has helped customers hold on to 19k pieces of Ikea furniture, saving 179 tons of CO2 emissions.

Consumers are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of their purchases: In our survey, 60% of respondents said eco-friendliness is an important consideration when buying home furnishings.

The Hustle

A report by the Retail Industry Leaders Association found that:

- 93% of global consumers expect the brands they use to address and consider environmental issues

- American consumers will spend up to 20% more on products that are environmentally friendly.

For its part, Ikea has announced buy-back programs and plans to be “climate positive” by 2030.

But for consumers who already have a house full of Ikea furniture, a little redesigning and repurposing may be the greenest course of action.

“We’re all in the business of making Ikea products last longer,” says Cagin, of Prettypegs. “We want to turn fast furniture into slow furniture.”