On a recent weekend in Salem, Massachusetts, I wandered into the Salem Witch Board Museum.

The site of America’s infamous witch trials in 1692, Salem is now a commercialized ode to occultism: It is home to dozens of witchcraft shops, ghost tours, and “haunted” abodes.

Inside the museum, the history of a fascinating business is on display.

The walls and glass cases of the small gallery are lined with “talking boards” or “witch boards” — devices that supposedly allow people to communicate with spirits.

A selection of talking boards at the Salem Witch Board Museum in Salem, Massachusetts (Juliet Bennett-Rylah)

They work like so:

- The board is labeled with the alphabet, numbers (0-9), and the words “yes,” “no,” and some variation of “goodbye.”

- A player asks the board a question.

- An indicator mysteriously moves across the board, spelling out an answer.

You might know these devices as Ouija boards. But Ouija is a brand, like Kleenex or Tupperware. And at one point in time, it was a multimillion-dollar business.

“Think of Coke and Pepsi. Coke is probably number one, Pepsi is number two. There is no number two for the Ouija board,” the museum’s owner, John Kozik, told The Hustle.

When Kozik points out other brands in the collection, guests often assume they won’t work as well because they’re not “official,” as though ghosts harbor a brand-name preference.

This is the story of how, thanks to the combined forces of spiritualism and capitalism, Ouija became the go-to for communing with the dead.

How spiritualism became a business model

Spiritualism — the belief that the living can communicate with the dead — was already popular in Europe when it ignited across the US in the mid-19th century.

America’s obsession with spiritualism can largely be traced to the Fox sisters of Hydesville, New York, who interpreted messages from spirits that rapped on furniture and walls.

But for aspiring mediums without knocking spirits at their behest, there were other communication devices, like the talking board.

Two women using an early talking board in the 1890s (Talking Board Historical Society)

At first, talking boards were something people made themselves.

An 1886 article described how easy the “new scheme for mysterious communication” was to construct: You just needed a board marked with letters and numbers, and a planchette (French for “little plank”) to point to them.

Users would place their fingers on the planchette, and spirits would channel through them to point it to the desired letter.

Among these early talking board enthusiasts was Charles Kennard, a fertilizer entrepreneur in Chestertown, Maryland. He didn’t seek answers from the great beyond so much as profit.

“He was one of those guys who’s always into seven to ten businesses, always looking for some cool opportunity,” Robert Murch, the president of The Talking Board Historical Society (and one of the nation’s foremost experts on Ouija boards) told The Hustle.

Kennard partnered with an undertaker and woodworker named E.C. Reiche to make and sell a dozen or so boards. Kennard suggested they go into business together, but Reiche failed to see a profit in something people could make themselves.

Kennard saw potential and kept at it.

After his fertilizer business dried up due to competition and drought in 1889, he moved to Baltimore to start anew. There, he met patent attorney Elijah Bond.

Call me Ouija

Bond was into Kennard’s business idea — and it didn’t hurt that Bond’s sister-in-law, Helen Peters, was a medium (someone who claims they can communicate with the dead).

In letters Murch uncovered, Kennard wrote of a seance Peters held in April 1890, during which he claimed they asked the board what it wanted to be called. It spelled “O-U-I-J-A,” then told the group it meant “good luck.”

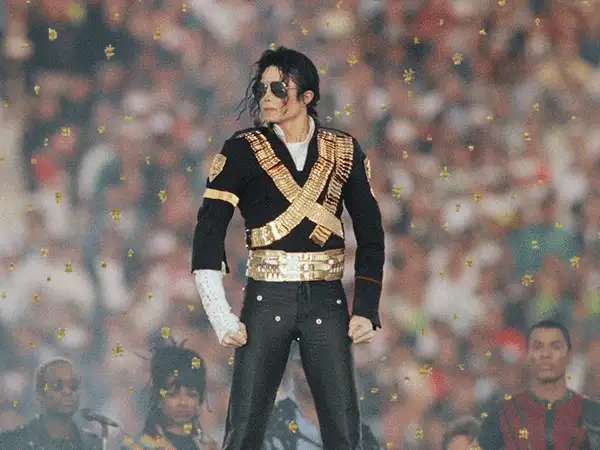

Early pioneers of the Ouija board: Charles Kennard (top left), E.C. Reiche (top right), Elijah Bond (bottom left), and Helen Peters (bottom right) (Talking Board Historical Society)

Ouija wasn’t a word in any language. Murch speculates it may have been a misspelling of Ouida, the sobriquet of Maria Louise Ramé, a writer Peters admired, but, whatever the case, it stuck.

Kennard incorporated The Kennard Novelty Company on Oct. 30, 1890, with investors Col. Washington Bowie, John F. Green, Harry Welles Rusk, and William H.A. Maupin.

Their mission? Selling as many Ouija boards as possible.

‘Proven at the patent office’

Bond’s role was to trademark the word “Ouija” and patent the board. Per Murch’s research, the patent office had rejected similar devices because their creators couldn’t prove they were summoning ghosts.

So, Bond brought Peters along. The pair were shuffled from clerk to clerk until they reached the office’s chief.

“The [chief clerk] walks in and says, ‘Look, I don’t know you and you don’t know me. But if that contraption can spell my name, you’ve got your patent,’” Murch said.

With Peters and Bond at the board, it revealed his name, letter by letter. The supposedly shaken clerk gave Bond his patent — and it gave Kennard a new tagline for the Ouija board in advertisements: “proven at the patent office.”

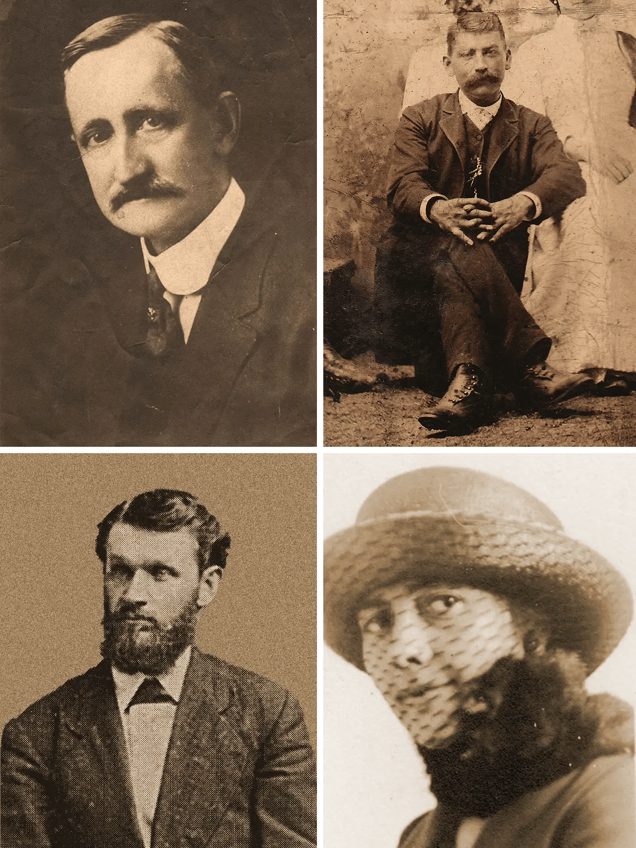

The original patent for the Ouija board, filed in 1891 (Google Patents)

By 1892, Ouija was so popular that the Kennard Novelty Company built additional factories in NYC, London, and Chicago, and a second in Baltimore. The boards sold for $1 (~$33 today) — a bargain for metaphysical messages.

The company’s leadership, however, had less staying power.

- Reiche, the undertaker, surfaced and asked for his cut of the profits, which Murch speculates left “a bad taste” in people’s mouths about Kennard.

- Kennard and Maupin cashed out in 1892, while Bond, who turned out to be terrible at business, departed after a disastrous attempt to oversee the UK factory.

Sans Kennard, Col. Washington Bowie renamed the company the Ouija Novelty Company, and enlisted William Fuld, his friend and a varnisher at the company, to manufacture the boards with his brother, Isaac.

The brothers did so until 1901, when Ouija, for reasons unknown, signed an exclusive agreement with William Fuld.

Big business

In 1918, Fuld built a three-story factory in Baltimore for $100k ($1.9m), purportedly because the Ouija board told him to “prepare for big business.”

Soon, the Ouija board was everywhere:

- It was a popular dating game among couples, as depicted in Norman Rockwell’s cover for a 1920 edition of The Saturday Evening Post.

- Songs, like “Weegee Weegee Tell Me Do,” “Ouija Mine,” and “Ouija Board” told of its powers.

- Bachelorette parties used it to predict guests’ romantic fates.

Left: The Ouija board graced the cover of the Saturday Evening Post in 1920; Right: A 1920s ad offering the Ouija for $1; Bottom: Ouija boards packed in a storefront window (Talking Board Historical Society)

With this newfound success, many competitors popped up.

Other manufacturers — including Kennard, Bond, and Fuld’s ousted brother — tried to cash in on the trend. But Fuld vanquished them all with lawsuits and pricing tactics (he undercut cheaper boards by manufacturing a discount “Mystifying Oracle” board).

Unfortunately, Fuld’s factory also killed him.

In 1927, he fell off the roof while supervising a flagpole installation and a broken rib punctured his heart. On his deathbed, he asked his children to never sell the Ouija board.

They honored his wish until there were no heirs who wanted to run the business. Then, in 1966, the Fuld family sold Ouija to Parker Brothers.

The Ouija goes corporate

Parker Brothers founder George Parker made his first game, Banking, in 1883 at age 16. It involved borrowing money from a central bank to see if you could make more.

By 1966, Parker Brothers was a flourishing company headquartered, like Kozik’s museum, in Salem — with games including Risk, Sorry, and Clue.

According to a 1986 interview with then-president Robert B.M. Barton, Parker Brothers paid a staggering ~$975k ($8.9m) for Ouija. It was the most expensive acquisition the company had ever made — it’d paid just $500 ($10.8k) for Monopoly in 1935 — but it paid off.

“I think I made the money back in two years,” Barton said at the time.

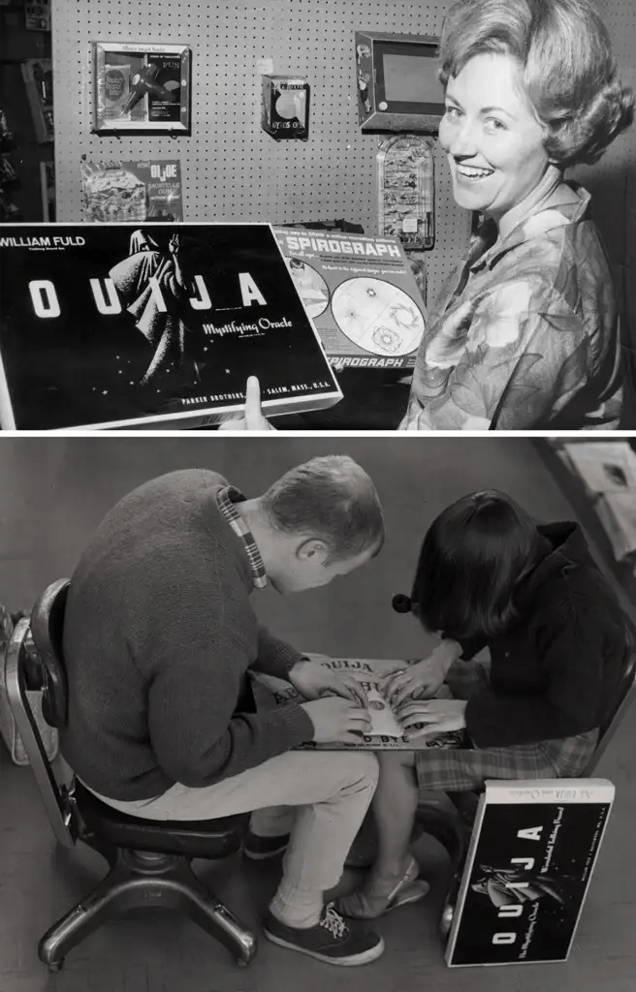

Consumers snapping up Ouija boards in the 1960s (Talking Board Historical Society)

Randolph Parker Barton, George Parker’s grandson and the company’s then-VP, said that when it acquired the patents, Ouija was selling ~400k boards per year, but had so many back orders, Parker Brothers wasn’t sure it could keep up.

In 1967 alone, Parker Brothers sold 2m boards, outselling every single one of its other 134 games — even Monopoly.

Though the Ouija board was a smash success, Parker Brothers lacked the finances to keep pace with the booming games business. In late ’67, the company was sold to General Mills.

General Mills had already purchased Play-Doh maker Rainbow Crafts, Inc. and Easy-Bake oven maker Kenner, which merged with Parker Brothers after the acquisition.

Tonka acquired Kenner Parker in 1987 in a deal worth $627m ($1.6B today), then sold to Hasbro for $516m ($1.1B) in 1991.

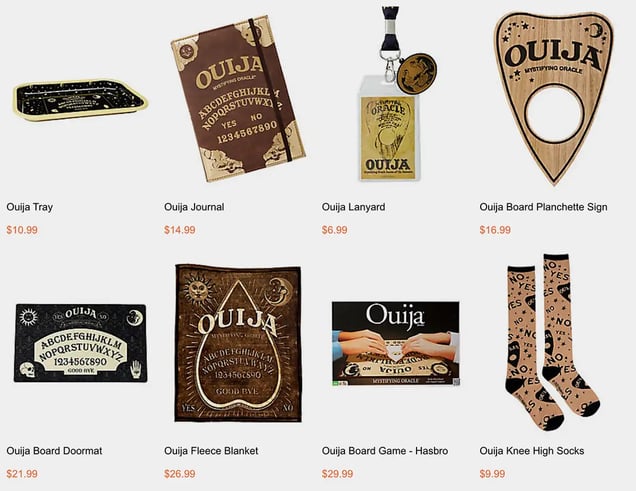

Hasbro retains the Ouija patent and trademark to this day, and occasionally licenses it to other companies:

- Winning Moves makes a classic version that harkens back to the ’80s and ’90s

- Bioworld Merch, which manufactures licensed apparel and accessories, sells blankets

- Spirit Halloween sells Ouija-themed merchandise, including party decor, mugs, and candles

The Ouija brand is in full capitalism mode at the Spirit store — it’s on everything from socks to blankets (Spirit Halloween)

Hasbro also produced two horror films, Ouija (2014) and Ouija 2: Origin of Evil (2016), both commercially successful. The first film took in a global box office of $103.6m against a budget of $5m-$8m, despite its mostly negative reviews.

Which raises the question: How did Ouija go from a spiritual tool to a flirty dating game to something scary?

Blame The Exorcist

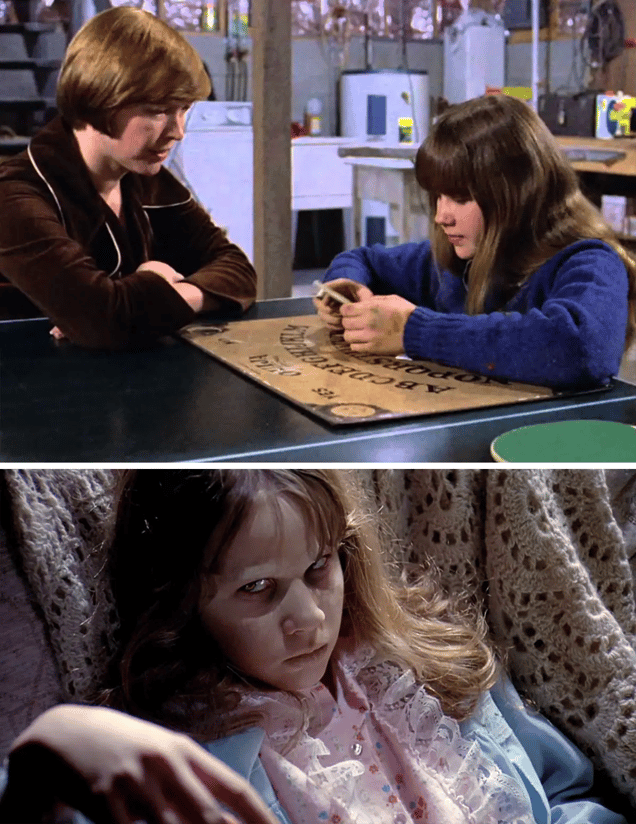

In 1973’s The Exorcist, 12-year-old Regan tells her mother she uses a Ouija board to talk to a spirit called Captain Howdy shortly before she’s possessed by a demon. Interestingly, Ouija sales went up 15% that year.

Sinister Ouija stories weren’t unheard of before The Exorcist, in both real life and pop culture. In the 1960 film 13 Ghosts, a levitating planchette warns of impending doom. In 1930, a New York woman convinced a friend to murder her romantic rival, claiming a spirit had ordered the deed.

The Exorcist’s greatest contribution to what Murch and Kozik call “Ouijastitions” is perhaps the idea that something bad could reach out if you used the board alone.

The Ouija Board made a prominent appearance in the 1973 film, The Exorcist (Warner Bros. Pictures)

It’s repeated in Kevin Tenney’s Witchboard (1986), in which Whitesnake video vixen Tawny Kitaen is ensnared by a malevolent spirit after playing alone; both Ouija films; and countless other media — over time cultivating a deep fear and demonic connotations.

And in 2008, when Hasbro released a pink Ouija marketed to young girls and sold exclusively at Toys R Us, some called for a boycott on Toys R Us.

Hasbro made a pink Monopoly as well. Kozik, who has the pink Ouija in his museum, asks what’s more evil: chatting with ghosts, or bankrupting all your friends.

Kozik’s museum also contains numerous boards mailed in by people hoping to rid themselves of a cursed artifact. One, Kozik told The Hustle, came packed in five pounds of salt.

But… does it work?

Ah, yes. The eternal question.

Remember the Fox sisters, who sparked the spiritualism movement in the US back in the mid-1800s? In 1888, one of them admitted — then recanted — that it had all been a hoax, but the spiritualism movement persisted without her.

To this day, there are many who believe that the Ouija board allows us to pierce the veil and seek advice from what lies beyond, or those who are so afraid of summoning a demon that they refuse to be near one.

The Ouija board remains mysterious to this day (Getty Images)

A more scientific explanation is the ideomotor effect, small movements we make without intending to or realizing we’re making them.

It could explain how Peters conjured a name similar to a writer she loved, or how Bond spelled out the name of a patent employee he — a patent attorney — perhaps already knew.

We’ll let you decide.

But one thing’s for sure: It turned into a pretty damn good business.