Way back in early 2021, when GameStop stock was soaring and cratering, when the phrase Bored Ape Yacht Club entered the lexicon, and when Bitcoin was pushing above $50k, celebrities and financiers were buzzing about another investment vehicle.

Chamath Palihapitiya, a venture capitalist, described this tool as a way to even “the playing field,” offering average people an opportunity to invest in high-growth companies. Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman planned to use one to “marry a unicorn.” Athletes like Shaquille O’Neal also got involved.

All of them were believers in SPACs. Remember them?

- SPACs, Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (or blank-check companies), are public shell companies created by investors. They go public through an IPO and seek to acquire a separate private company within two years and take it public.

- The merged company, sometimes called a deSPAC, gets listed on the stock market — often faster than it would through a traditional IPO.

SPACs were supposed to be a revolution. In February 2021, when Alex Rodriguez, the former New York Yankees baseball star, announced his SPAC, he said, “This is only the beginning.”

Alex Rodriguez (Michael Loccisano/Getty Images)

More than two years later, SPACs have faded into obscurity, the boastful dreams of many business titans giving way to an austere reality:

- Rodriguez’s SPAC has yet to find a company to merge with, and Ackman’s unicorn-seeking SPAC was liquidated.

- O’Neal’s Forest Road Acquisition Corp. SPAC merged with BeachBody, which was trading at 15 cents per share as of November 15.

- Palihapitiya, the king of SPACs, developed six SPACs, five of which merged into new stocks that each lost at least 70% of their value. He reportedly made $750m from selling his shares — and was sued.

Those are just a few SPAC stories, but they’re emblematic of the phenomenon. Most of the hundreds of SPACs that formed at the height of the 2021 craze didn’t complete mergers, and most companies that went through a merger process turned into nightmares for average investors.

Why did SPACs fail so badly? And will they ever become popular again?

Forming a SPAC at the peak of the bubble

SPACs didn’t come into existence overnight — although it certainly felt that way. Back in the 1980s, blank-check companies began pairing with penny stock companies, many of which were fraudulent. SEC reforms helped create a legitimate SPAC structure in the 1990s, but SPACs were still a curiosity reserved for hardcore traders who bought and sold them outside of mainstream stock exchanges.

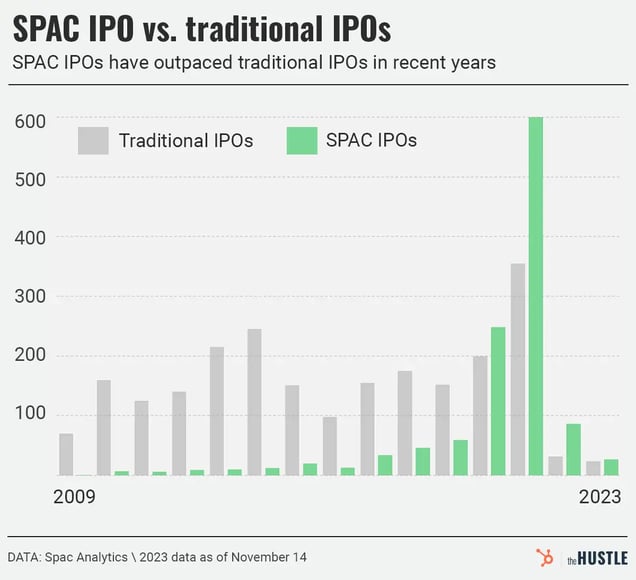

That started to change in the 2010s when major exchanges listed SPACs. In 2019, 59 SPACs held IPOs, the most since 2007. The number soared to 248 the next year.

And then came 2021. A whopping 613 SPACs went public.

The Hustle

The growth coincided with basement interest rates and an increased desire among early stage private companies to go public during a record bull market.

“A lot of venture capitalists and entrepreneurs,” says Jay Ritter, a finance professor at the University of Florida, “were thinking, ‘Hey, now is a really good time to go public. And maybe we can do this faster before market conditions turn against us.’”

And they believed it was quicker to go public via a SPAC merger than a traditional IPO or a direct listing.

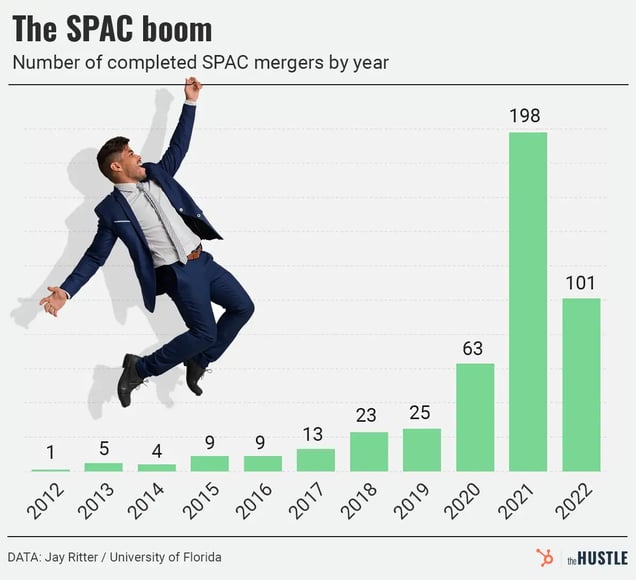

In 2019, the number of completed mergers between a private company and a SPAC was 25, rising to 63 in 2020 and 198 in 2021.

The Hustle

To sum it up, in early 2021, two things were happening: a helluva lot of SPACs formed, and a helluva lot of companies were merging with SPACs. And while it might seem like the increase in SPACs and SPAC mergers would’ve made for a perfect match, that wasn’t exactly the case:

- The companies that sought SPAC mergers in 2021 largely merged with SPACs that went public the previous two years — not during the boom of 2021.

- Most of the SPACs that got in during the frenzy of 2021 were too late.

Those SPACs needed the good times to continue into 2022 and 2023. Spoiler alert: They did not. SEC rule changes slowed the process of a SPAC merger, plus the stock market faltered.

In 2022, the number of SPAC mergers fell by roughly half, to 101. As of early November this year, Ritter says, just 75 SPAC mergers had occurred.

Given the downturn, Ritter estimates two-thirds of the 613 SPACs that IPO’d in 2021 will never complete a merger and will “end up losing everything.” Many have already liquidated, i.e. dissolved and returned money to investors.

When a SPAC liquidates, the biggest losers are the sponsors, the executives and private equity firms that start the SPAC and contribute sponsor capital, roughly 3%-7% of the predicted capital raise for the IPO. For an average SPAC in 2021, the upfront cost of sponsor capital was ~$8m, Ritter says.

At the height of the SPAC craze, these sponsors believed they’d get richer. Instead, with ~400 of the 2021 SPACs likely to fail, they’ll be out a combined ~$3.2B.

How average investors took a hit

Losses when SPACs fail to merge typically affect just the SPAC sponsors. But average people have lost for another reason: investing in a company that merged with a SPAC.

- In 2020 and 2021, at the height of the SPAC craze, retail investors were lured to SPACs by promises they could buy shares in a company at an early stage and reap the benefits, similar to a venture capitalist.

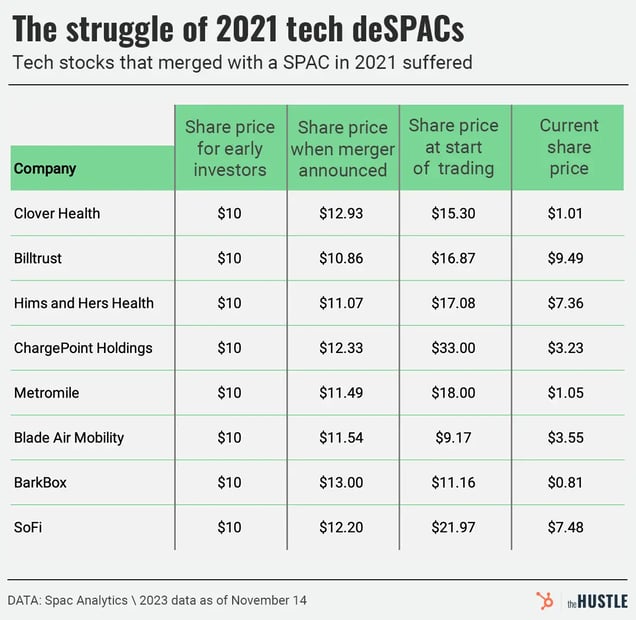

- But the average one-year return on a company that went public via SPAC merger in 2021 was -64.2%, according to Ritter’s data. (The average one-year return for the entire market was -10.4%.)

It wasn’t a fluke: Ritter’s data, which goes back to 2012, shows that deSPAC companies have significantly underperformed the market every year.

BuzzFeed went public via SPAC in December 2021, opening at $10.45 per share. Its stock now trades at ~$0.32. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Why have the results been so poor? Analysts have pointed out that many companies that went public via SPAC in 2020 and 2021 were risky: unprofitable tech companies and biotech firms in the first stages of developing new drugs.

But the lack of success may also have to do with the SPAC process itself.

Research by New York University law professor Michael Ohlrogge, Stanford University law professor Michael Klausner, and management consultant Emily Ruan indicated the poor returns for companies that went public via SPAC are a product of structural flaws that benefit SPAC sponsors and select hedge funds to the detriment of average investors.

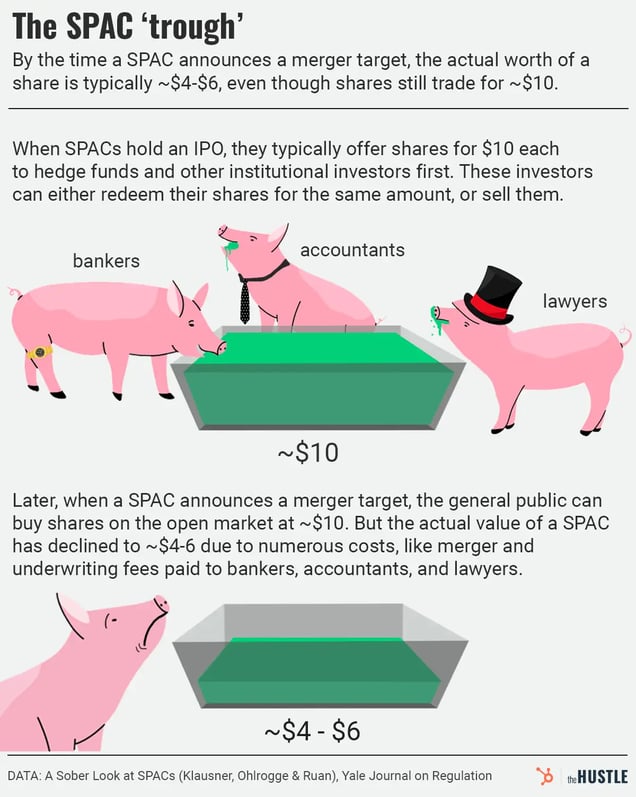

- When SPACs hold an IPO, they typically offer shares for $10 to hedge funds and other institutional investors (groups known in the industry as the SPAC mafia).

- In what basically amounts to a risk-free investment, SPAC mafia investors can either redeem their shares for the same amount, plus interest, or sell them. They also receive warrants, which give them the opportunity to purchase future stock at a set price.

- Later, average investors can buy shares on the open market, usually at the same price of ~$10. These investors typically don’t get involved until a merger target is announced.

- Although the share price still usually hovers around $10 at this stage, the actual value of a SPAC has declined, Ohlrogge says, because of numerous costs: merger fees and underwriting fees paid to bankers, accountants, and lawyers; the warrants granted to the early institutional investors; and sponsor shares. (Sponsors, in exchange for setting up the SPAC, receive ~20% of shares at a minimal price.)

“You have all of these people coming to feed at the SPAC trough, pulling value out,” Ohlrogge says.

The Hustle

So, around the time a SPAC announces a merger target, Ohlrogge, Klausner, and Ruan found the actual worth of a share is typically ~$4-$6, even though shares still trade for ~$10 — or sometimes higher. At the height of the SPAC bubble in late 2020 and early 2021, share prices jumped to an average of $15.77 the day after an announced merger, leading to a more-expensive buy-in for average investors and an alluring selling price for the SPAC mafia.

As complicated as this sounds, it basically means that a share of the merged entity is overpriced. The average investors who buy stock overpay — bearing the costs of the various fees, as well as the benefits afforded to sponsors and early institutional investors — setting them on a difficult path to receiving a decent return.

A few companies that merged with SPACs did beat the odds for investors. Shares in the gambling platform DraftKings were trading at ~$38 in mid-November, roughly double the price from the day DraftKings went public.

But it’s a rare exception. As of April 2023, according to SPAC Research, more companies that went public via SPAC between 2020 and 2022 were trading at below $1 per share than at above $10 per share.

Early investors made gains selling early, while average investors struggled. Note: Billtrust and Metromile are no longer public and current share price reflects last available price. (The Hustle)

For years, Ohlrogge says SPAC proponents dismissed the poor track record of SPACs, insisting it would be different with better sponsors and better target companies.

“And it’s never been true,” Ohlrogge says. “So they just keep continuing to perform badly, and I think it’s because they have these enormous structural flaws that still very few people understand.”

Death by lawsuit?

The paper by Ohlrogge, Klausner, and Ruan came out in fall 2020, just as the SPAC fervor was becoming a mania. Despite being widely disseminated, it did little to deflate the SPAC bubble or reform the way SPACs are structured.

Lawsuits might.

- Klausner, co-author of the paper, has represented plaintiffs in three lawsuits against SPACs in Delaware Chancery Court, claiming the SPACs obscured their true value from public investors because of the benefits given to sponsors and the hedge funds that get in early.

- In 2023, a judge heard Klausner’s argument in one case and ruled it could go to trial, prompting SPAC proponents to fear an onslaught of lawsuits against SPACs and a more difficult climate for SPACs in the future.

But Ohlrogge puts the probability of SPACs disappearing at ~33%. For one thing, a judicial precedent would be binding only in Delaware. That’s the state where the majority of SPACs were incorporated in 2021, but SPACs could sidestep any new rules by incorporating in the Cayman Islands, as many already have.

The more likely scenario, Ohlrogge says, will be that SPACs survive and remain somewhat popular, perhaps rising again in prominence with another bull market.

To paraphrase SPAC aficionado Alex Rodriguez, then, the 2021 SPAC bubble may be only the beginning.