In the opening sequence of The Bourne Identity, a young Matt Damon wakes up with no idea who he is. All he has is a code — the account number for a safe deposit box in Switzerland.

At the bank, an attendant leads him into an elaborate steel vault, where he’s presented with a safe deposit box. Inside are the first clues to his identity: a gun, a watch, stacks of cash, and a series of passports under different nationalities, including one bearing the name “Jason Bourne.”

Over the years, safe deposit boxes have become iconic — a staple not only of the banking industry but also of heist movies and spy flicks. Inside Man, The Dark Knight, Casino, and The Da Vinci Code all feature pivotal safe deposit box scenes.

In Hollywood, safe deposit boxes are so prominent, in fact, that it’s easy to miss the seismic changes racking the industry: In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, big banks have quietly abandoned the safe-deposit business.

Both HSBC and Barclays have shuttered their safe-deposit services in many countries, and Capital One joined them in 2016. Most recently, this past September, JPMorgan Chase announced it was phasing out its safe deposit boxes, too. In the coming decade, other major banks seem likely to join them.

What went so wrong?

The rise of the safe deposit box

The Civil War was just days away when a New York businessman named Francis Jenks stumbled on an idea that would change the face of the banking industry.

In March 1861, while on a trip to England, Jenks — the moneyed son of a Harvard professor — began to wonder what he was supposed to do with his valuables while he was out of town.

He decided to create a company that would store items for New York’s “fashionable inhabitants,” who wanted to, say, decamp to Europe for the summer.

Rather than worry about burglaries, Jenks suggested that the urban elite store their books, wills, jewelry, tea sets, and silver with him.

He opened a massive, marble building in lower Manhattan, complete with a thick steel vault. Inside, he offered 500 safe deposit boxes to customers.

A man accessing his safe deposit box in the 1930s (H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images)

To ensure the safety of the boxes, Jenks required two keys to unlock a box: one key for the customer and one key for his employees. Guards armed with muskets stood in front of the building at 146 Broadway through the night.

He called it the Safe Deposit Company of New York.

It was the first company of its kind — and as the Civil War broke out, demand soared. Bold-faced names like the Vanderbilts, the Guggenheims, the Roosevelts, and more began storing their valuables with Jenks. Hetty Green, the millionaire businesswoman, maintained a private vault so big that it could fit a desk inside of it.

It was such a success that copycat safe deposit box companies began proliferating across the US, with names like the Mercantile Safe Deposit Company and the Lincoln Safe Deposit Company.

While the first safe-deposit companies were stand-alone organizations, dedicated solely to safekeeping, major banks soon got involved. By the early 20th century, nearly every bank in America had a safe-deposit arm.

The tricky economics of safe deposit boxes

In the decades after Francis Jenks created the Safe Deposit Company of New York, the safe deposit box industry had a clear internal logic.

Stockpiles of gold and jewelry were a staple among the wealthy, and so were wills and stock ownership documents. In an era in which fires were common and home security systems weren’t very complex, the choice was simple: store your valuables with your local bank.

People began dumping all kinds of prized possessions into safe deposit boxes, including:

- A Honus Wagner baseball card that later sold for $220k

- An Abraham Lincoln campaign button

- Purple Heart medals

- A supposedly forged Van Gogh painting

- An NFL ticket from the 1950s

- Sets of false teeth

- Albert Einstein’s eyeballs (once owned by the physicist’s eye doctor)

All kinds of valuable and strange things are stored in safe deposit boxes (various sources)

Even famous authors used safe boxes: Harper Lee’s lost book Go Set A Watchman was found in her safe deposit box, potentially alongside other unpublished works.

“We end up insuring first-edition book manuscripts, movie paraphernalia — it’s kind of all over the place,” said Jerry Pluard, a former lawyer who now sells insurance policies on safe deposit boxes through his company Safe Deposit Box Insurance Coverage. “Certain clients are insuring Olympic medals with us.”

Yet the economic logic of safe deposit boxes quickly began to erode. In the early 1900s, bank executives confronted a troubling problem. Safe deposit boxes weren’t actually raking in big profits.

In 1941, one industry expert admitted, “It is not inconceivable that a vault might be 100 per cent rented and still be operating at a loss, due to low rental rates.”

One problem was that the cost of building a vault for safe deposit boxes put companies in the red almost immediately.

These vaults are made with heavy concrete and layers of reinforced steel, and they are built to withstand the unimaginable. One bank vault, made by the American company Mosler Safe Company, survived the nuclear bomb in Hiroshoma in 1945.

But the ability to withstand a nuclear explosion comes at an incredible financial cost.

Safe-deposit vaults are “the most expensive square footage you can put in a branch location,” said David McGuinn, who has educated banks on safe deposit boxes through his consultancy Safe Deposit Specialists for over thirty years.

Though some banks have tried to compensate for the costs by upping their rates, it rarely works for long. In the 1980s, a crop of new safe-deposit businesses began charging as much as $600 per year for boxes that customers could get for $60 elsewhere. Many of these quickly crashed and burned.

The issue? Competition from home security. If bank boxes are much more expensive than, say, a home safe or a home security system, customers will opt for the latter.

Getty Images

Safe deposit also came with a handful of legal headaches. Banking industry executives fretted over hypothetical scenarios about when they would let a customer in to see their valuables.

In 1937, Bankers’ Magazine asked if bank staff should let a customer in if she or he arrived at a bank drunk and intended to take out valuables. Experts couldn’t agree.

But banks made peace with these financial and legal quandaries. The point of safe-deposit services, they decided, was not to turn a profit on safekeeping itself. Instead, banks saw them as a way to build customer loyalty.

“It’s the hardest account for a consumer to close,” said McGuinn.

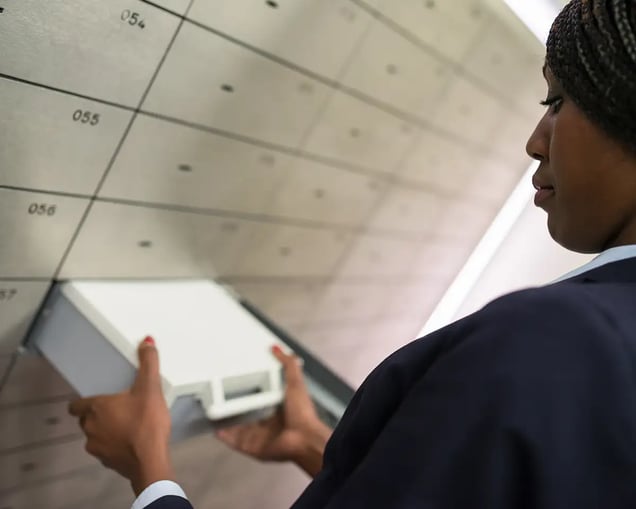

Unlike with a regular deposit account, you generally can’t just close a safe deposit box online or over the phone. You have to show up to the bank branch in person with the keys, fill out paperwork, and then empty the contents of your box.

Shuttering a safe deposit box is such a hassle, in fact, that if a customer signs up for one, “it’s an incentive for these people to stay with the financial organization,” according to McGuinn.

The final straw for the big banks

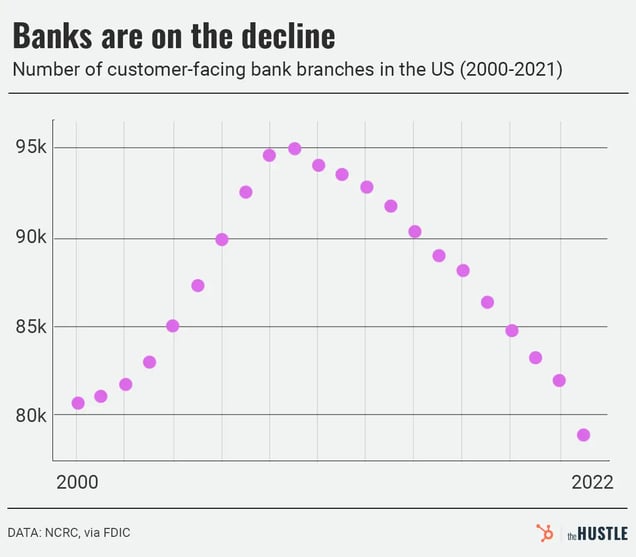

The economics of safe deposit boxes started to break, at least for the major banks, as the cost of commercial real estate ballooned. The number of bank branches peaked around the time of the 2008 recession, and have plummeted ever since.

Between 2017 and 2021 alone, the number of bank branches in the US fell by 9%. With big banks focusing on fewer — and smaller — physical locations, safe deposit boxes were among the first to go.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

At the same time as bank branches are disappearing, more people are turning to digital assets. New asset classes, like crypto, are supplanting physical commodities, and a growing number of people have digital wills that don’t need to be tucked in a safe deposit box.

The ultra-wealthy, meanwhile, seem to have abandoned traditional bank vaults. In recent years, high-end, independent safe-deposit companies have popped up to court the world’s wealthiest consumers.

Rather than store their valuable art in a box at a downtown bank, rich people can turn to ultra-secure, steel-lined vaults built in converted mansions. One vault, offered by companies like International Bank Vaults (IBV), is accessed by a corporate Rolls-Royce. Guests then scan their fingerprints and irises before stepping inside.

“It’s a relic. The business is fading away,” the executive director of the New York State Safe Deposit Association said in 2013 — shortly before the trade group itself folded.

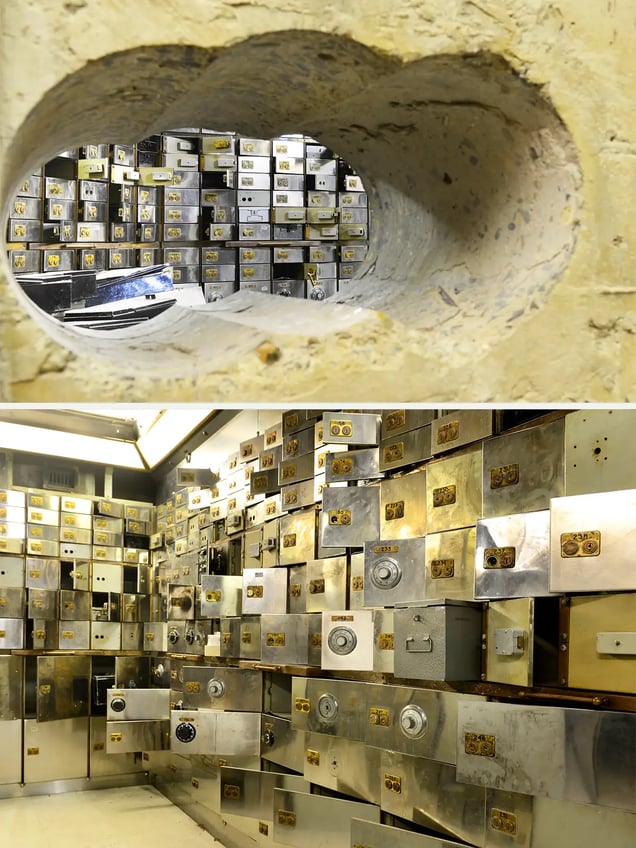

An ironic legal quandary has been equally detrimental to the safe-deposit business: Safe deposit boxes aren’t actually safe.

FDIC insurance began in 1933 as a part of the New Deal, around when the safe-deposit industry was at the height of its power. But unlike regular deposit accounts, safe deposit boxes are not FDIC-insured — meaning that if a valuable item disappears or is destroyed, safe-deposit customers have little way to get their money back.

That lack of protection is a hassle for customers, but also for banks themselves. They often face lawsuits about lost or misplaced items, which can be expensive to settle.

When US-based safe boxes are broken into — like they were in this $14m heist at London’s Hatton Garden Safe Deposit Ltd in 2015 — customers often have no recourse (Peter Dazeley/Getty Images)

Through his consultancy, “I’m talking to bankers at Wells Fargo and Bank of America,” said McGuinn. He often hears grumbling about the state of the business. The feedback he gets from the big banks is simple: “They don’t really want this service.”

Though no industry group tracks safe deposit boxes nationwide, Pluard thinks it’s safe to say that the number of available boxes has been dropping.

He conducted an informal study of the industry in 2011, when he was preparing to launch his safe deposit box insurance company. At the time, he estimated that about 40 million safe deposit boxes had been rented.

Pluard guesses that there has been “probably a 25% decline” in the number of rented boxes over the last decade.

The accidental safe-deposit shortage

For big banks, operating safe deposit boxes no longer makes financial sense. But as the likes of Chase and Capital One exit the safe-deposit business, they have accidentally created an intractable problem for consumers.

People still want safe deposit boxes — and now it’s nearly impossible to get one.

“While the total amount of boxes available to be granted is shrinking, the usage isn’t shrinking as fast,” Pluard said. In cities, “there are shortages of large boxes. People on lists wait years to get a box, whether it’s in New York, whether it’s in Miami, whether it’s Charlotte.”

Safe deposits are fading away (Getty Images)

Many regional banks and credit unions are promoting their safe-deposit services, mostly because it aligns more closely with their goals. Big banks are pushing people toward increasingly elaborate mobile banking apps. Credit unions, on the other hand, deal with customers face to face.

But if you don’t have an account with a local credit union, you might be out of luck.

For people with valuables they want to store at a bank, finding safe deposit boxes to rent can feel a bit like the Hunger Games.

In New York City especially, it’s not unusual to visit multiple bank branches — and find that none has the capacity for new safe-deposit customers.

On Yelp, one user reported walking into a bank in Brooklyn. When he said he wanted a box, he was dumbfounded by the response: The wait, the teller told him, would be about nine years.