In 1998, the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association — the industry’ largest trade group — gave a pair of meat scientists $1.5m in grant money and a seemingly impossible mandate: Find a new cut of meat that centuries of professional butchers had missed.

Three years later, the world was introduced to the flat iron steak.

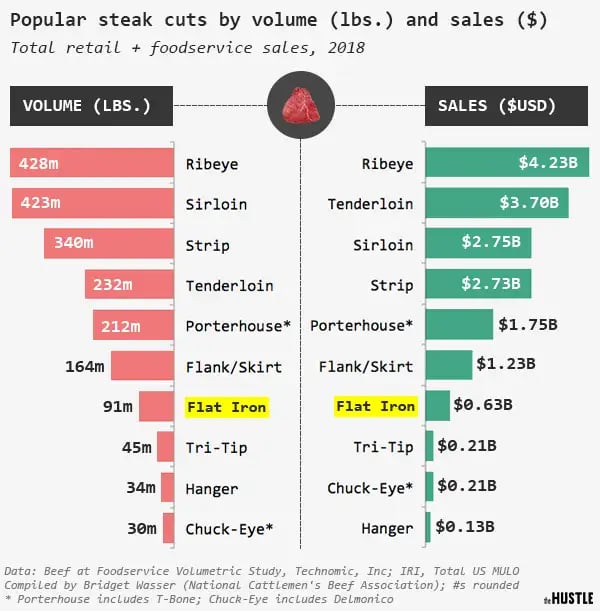

In its first several years of life, the flat iron steak — a very thin, very tender cut from beneath the shoulder blade of the cow — topped 92m pounds per year in sales, about as much as the porterhouse and the T-bone steak combined.

Back then, it was rare to see a new steak enter the market. The flat iron became a proof-of-concept for the industry — and it left the beef titans craving more new cuts.

Cows have been around for millenia. How, exactly, do you discover a new steak? And once you discover it, how do you convince the world to give it a shot?

To understand how this process works, we traced the journey of the flat iron steak from lab to table.

From “lab flunky” to meat scientist

You might introduce Chris Calkins as the co-discoverer of one of the most popular steaks in America. But his more understated title is “University of Nebraska professor of meat science.”

Calkins didn’t dream of becoming a meat scientist. As a kid, he used to say he wanted to work as a vet. He grew up in a small town in Washington with a father who’d spent much of his life on a ranch.

When his high school mentor, an agriculture teacher, left to become a meat science professor at Texas A&M, he told Calkins to apply.

Chris Calkins (University of Nebraska / photo illustration by The Hustle)

Sure enough, Calkins got in. And within the year, he’d become a full-fledged “meat lab flunky” — the undergrad tasked with the laboratory cleanup work. But he fell in love with the work. “I was attracted to it because there were objective things that you can measure,” Calkins says.

By the 1980s, after nearly a decade of schooling, Calkins landed his position at the University of Nebraska. He started out studying meat color and dry-aged versus wet-aged beef. But his big break didn’t come for another decade.

Back in the mid-1990s, the beef industry had a problem. An oversupply of meat had sent the price of a cow tumbling. By 1996, some supermarkets were selling beef at 25% to 50% off the 1993 levels.

With ranchers at risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy, the NCBA came up with a solution.

Cows, they decided, were being underutilized. There were too few popular steaks out there: Sure, everyone wanted to buy a filet mignon, but a handful of cuts couldn’t carry an entire industry. If meat execs wanted to bring up the price of a cow, they needed to make people fall in love with other steaks.

The trade group put out a meat-science bat signal — an urgent call for research proposals. Calkins submitted an idea, and the NCBA paired him up with Dwain Johnson from the University of Florida.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

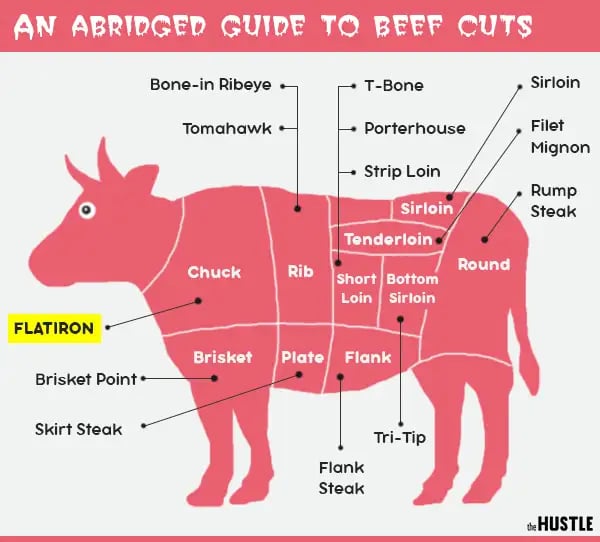

Understanding their proposal requires a bit of knowledge about bovine anatomy.

When it comes to taste, not all cow parts are created equal. Our most beloved steak cuts — the filet mignon, the prime rib, the ribeye — typically come from the inner parts of the cow, like the rib and the loin. Those regions are least involved in locomotion, so they tend to have the softest (and best-tasting) muscles.

The least desirable parts of the cow were those ones on the end — the “chuck” (the foremost region) and the “round” (in the back). The chuck and the round were far tougher than, say, the loin, and while meat packagers would carefully cut expensive steaks out of the loin, they sold the chuck and the round as cheap ground beef.

Common beef wisdom said that you couldn’t cleave a nice steak out of the chuck or round. So, prices of each stayed low.

But Calkins and Johnson suspected that the industry might have it all wrong. What if there was a way to slice the chuck and the round that produced a steak as delicious as a tenderloin?

‘It’s like a puzzle’

The team split into two groups: In Nebraska, Calkins handled the compositional analysis, looking at things like water-holding capacity and fatness. Back in Florida, Johnson measured the tenderness profile and directed the taste test panel.

After an initial analysis, the duo picked 39 muscles from the chuck and the round that they wanted to examine most closely. What followed was a grueling, 3-year process of carving out the muscles and testing them for tenderness and flavor. Calkins and Johnson gathered up 140 different renditions of each muscle. In total, ~5.5k slabs shuttled in and out of their labs.

Calkins demonstrating some fresh cuts (courtesy of Chris Calkins)

Early on in the process, one muscle stuck out.

Embedded in the chuck was the infraspinatus, located just beneath the shoulder of the cow. When Calkins and Johnson first analyzed it, they realized it was extremely tender, much more so than the hard exterior of the chuck.

But down the middle of the muscle was a large, rough seam of connective tissue. If Calkins and Johnson wanted the infraspinatus to become a steak, they were going to have to figure out not just how to cut it, but how to do it efficiently.

Meat packaging plants, some of which process thousands of cows per day, constantly assess whether or not certain cuts are worth the extra effort. You can find the most delicious piece of meat in the world, but if it takes a packager 5 extra minutes to remove, then they won’t do it.

“It’s like a puzzle,” Calkins says. “Someone says, ‘Okay, here’s a muscle. Figure out how to cut it to make it accessible.’ So you try everything you can. You worry about how much labor it’s going to take. You worry about, can the industry produce this product?”

Calkins took a few stabs at the infraspinatus. The connective tissue was thicker on one side than the other, so at first he tried to cut it out only on the thicker side.

When that failed, he landed on the idea of just cutting the connective tissue out entirely. That also seemed to be a bust. “When we first cut this thing, we said, ‘Well that won’t work, it’s too thin,’” Calkins says.

Calkins and Johnson decided to test it anyway. When they started to cook the slice, something extraordinary happened: “It plumped up,” Calkins says. That thin piece of meat? It got bigger.

Dwain Johnson exploring a fresh slab of beef (courtesy of Dwain Johnson)

Before they got too excited, they needed to get other people to weigh in. Johnson was directing a sensory panel, which was made up of 12-15 people recruited from the University of Florida — a mix of professors, students, janitorial staff, and retired employees.

To qualify, the team went through 12 hours total of training on the ins and outs of measuring, say, tenderness. When Johnson served them a steak, they weren’t supposed to say whether or not they liked it, just whether it passed some objective markers of tenderness, juiciness, and flavor.

When Johnson gave them this ultra-tender cut from the chuck — soon to be known across the country as the flat iron steak — he realized he and Calkins might have a hit. “It stood out,” Johnson says. “As we were going through the process, we said, ‘This has potential.’”

A new steak goes to market

To hear Calkins tell it, when he first took the new steak to meat industry execs, their reaction was, “You’re kidding, right?” The flat iron was so thin.

“It took a while to convince processors to cut it. It took a while to get retailers and restaurants to understand what the steak was like,” Calkins says. “Then eventually, the whole industry said, ‘It looks like there is value in doing this.’”

To get the cut out there, Calkins and Johnson started going on tour. Sponsored by the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, they visited conventions, where they showed chefs how to cut a flat iron steak. An event at the University of Nebraska introducing the new steak brought 100+ meatpackers and other industry bigwigs.

Top: A Los Angeles catering chef preps a rack of flat iron steaks in 2009 (Allen J. Schaben/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images); bottom: a grilled flat iron steak at Heritage of Sherborn in Sherborn, Massachusetts in 2016. (Barry Chin/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

The NCBA started setting up shop in grocery stores. Representatives would man meat sample tables and say, “Hey, take a bite of this new steak. And people would go, ‘Oh my god, it’s so tender, where do I buy this?’” says Calkins.

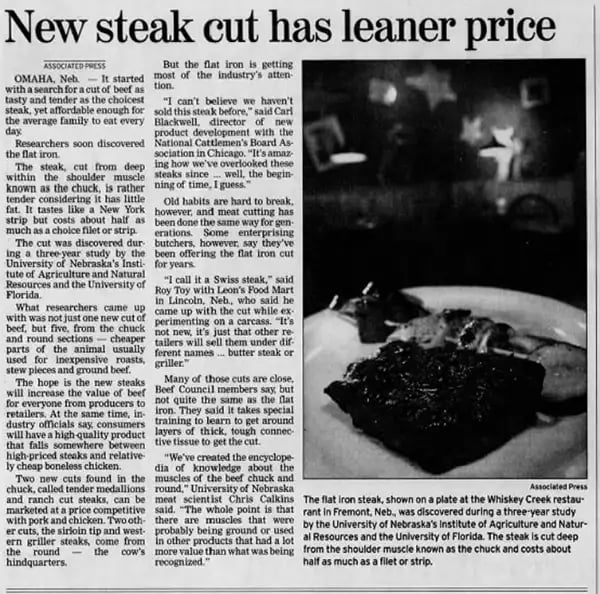

In November 2001, the flat iron steak began its public press run. In an Associated Press article, “New Steak Cut Has Leaner Price,” the wire service trumpeted the discovery of a slice of meat that “tastes like a New York strip but costs about half as much as choice filet or strip.” “It’s amazing how we’ve overlooked these steaks since… well, the beginning of time, I guess,” the director of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association told the AP.

Of course, the idea of a “new” cut touched off some tricky politics about whether you can really discover a slice from an animal that has existed for millennia. One grocery, Leon’s Food Market, said that it had been cutting that same muscle and calling it the “Swiss Steak” before Calkins and Johnson ever entered the fray.

But beef experts noted that while the Swiss Steak shared some qualities with the flat iron, they weren’t a 1:1 match. “It takes special training to learn to get around layers of thick, tough connective tissue to get the cut,” the AP wrote.

Getting the flat iron steak into the beef ecosystem took more than just Calkins, Johnson, the NCBA, and the AP. Seeing the profit potential of a new cut of steak, an entire network of nonprofits and trade groups jumped into the mix.

A 2001 AP article tours the tenderness and affordability of the newest steak on the block (The Pantagraph/AP, via newspapers.com; 11/08/2001)

Diana Clark, a meat scientist at Certified Angus Beef — an organization for cattle breeders that appraises the quality of certain steaks — has spent years trying to popularize new and overlooked meat cuts.

In normal times, that means she regularly welcomes in groups of chefs and retail representatives into her Ohio office, where she demos new cuts. About 30 people are in and out each week. (Lately, she’s been trying out Zoom demonstrations.) Back in the early 2000s, Certified Angus Beef used the same strategy to promote the flat iron steak.

The way the supply chain works, Clark says, is that you have to corner the restaurant market first. The big distributors — Sysco, PFG, and US Foods — are reluctant to try a new cut until they’ve seen proof of demand.

“If they keep hearing, ‘We want this flat iron cut, we want this flat iron cut,’ then food distributors will listen,” Clark says.

That strategy worked. In the early 2000s, Applebee’s became one of the first major chains to put the flat iron on its menu. By 2006, Kroger’s added the flat iron to 1.8k of its stores. Suddenly, that strange little piece of steak that Calkins and Johnson extracted in a lab was everywhere.

A marketing manager for the NCBA told Calkins, “This was an 8-year overnight success.”

Beefing up the price of a cow

The flat iron wasn’t the only new steak to hit the market in the mid-2000s. Calkins and Johnson had identified a number of promising new cuts, and they soon noticed those discoveries — like the ranch steak and the petite tender — inching their way into grocery stores.

If the industry’s mission was to drive up the price of a cow, the plan worked in a big way. According to analytics service CattleFax, by 2009, these new steak cuts had added $50 to $70 to the value of a single cow.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle (data via Bridget Wasser)

And beef bigwigs didn’t stop there. The end of the decade featured unveilings of new cuts from the chuck and the round that were first discovered by Calkins and Johnson. 5 rolled out in 2009, then another 6 hit the market a year later.

None has entered the zeitgeist quite as much as the flat iron steak. But even 2 decades later, that 1998 study has continued to shape what we eat.

When I asked Diana Clark what she sees on the horizon for the beef industry, she listed a few cuts that have caught her eye — the merlot steak, the Baltic steak. But one in particular has distinguished itself: the Denver steak.

That cut traces back to Calkins and Johnson. The Denver steak was the 4th-most tender slice in their study, taken from the chuck. It’s been around since 2009, when newspaper coverage called it a “distant cousin” of the New York strip. But only in the last few years has the industry really given the Denver steak a big marketing push.

“We’ve been promoting the Denver steak a lot more than we had in the past,” says Clark. “I can see it becoming the next flat iron.”