Ian Miller, owner of the Slaughterhouse in Des Moines, Iowa, makes a living out of scaring people to death.

The job is a culmination of a lifelong dream (ahem, nightmare) that started when he was a secular-leaning youngster in a Christian household, a teen who “went to church on Sunday and worshiped Satan on Friday.”

In 2010, he started a haunted house as a side business, cycling through business partners and doing whatever he could to break even. “I lived in very creative ways, alternative ways to aid and abet my pursuit for the ultimate terror,” Miller says.

Translation: For a time he lived out of a car. Sometimes, he slept inside his own haunted house.

Over a decade later, the Slaughterhouse has achieved profitability and renown in Des Moines. Still, even though his days of sleeping in a haunted house are over, he doesn’t always rest easy.

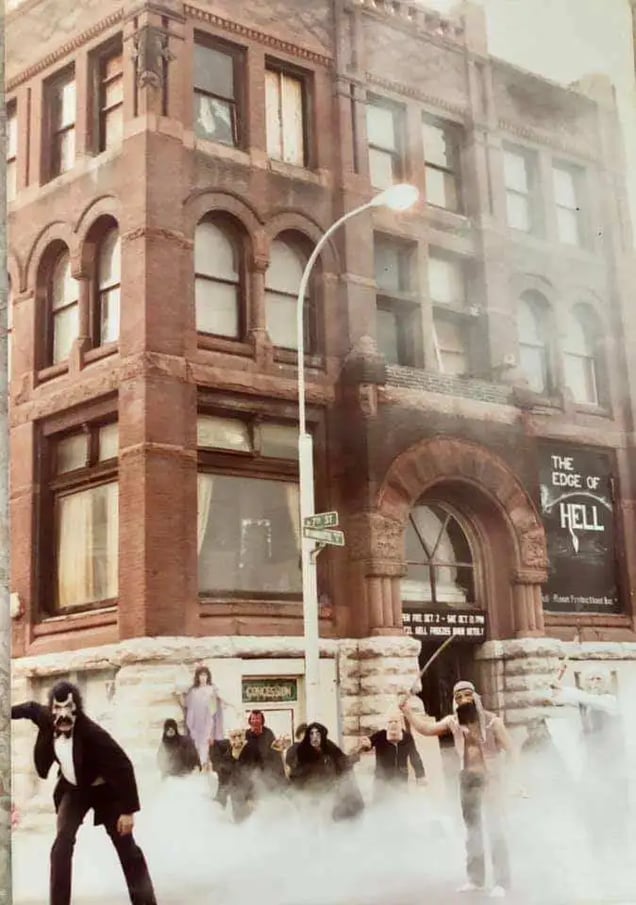

Greeters outside the Slaughterhouse. (The Slaughterhouse via Facebook)

Despite Halloween’s ever-increasing popularity, haunted houses are risky endeavors, labor-intensive businesses that must earn a year’s worth of income over a few weekends in September and October.

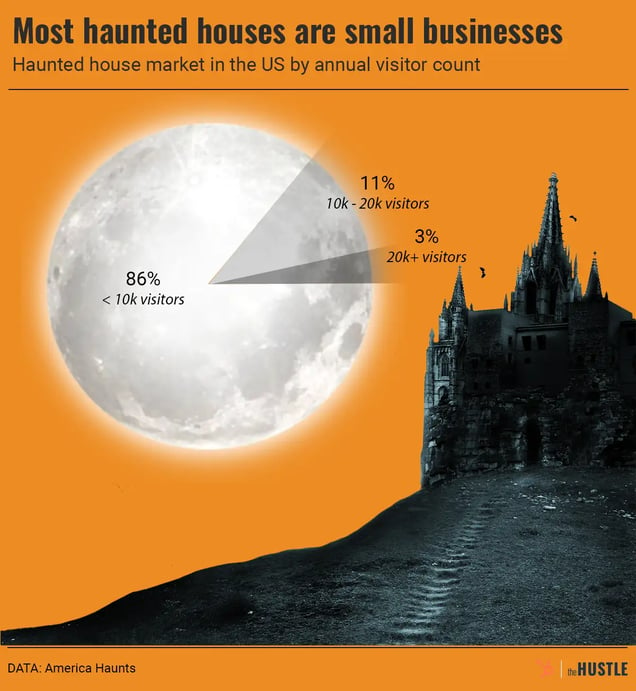

Only a small number of haunted houses see more than 10k visitors annually and stick around for longer than a few years. Even for the established houses, survival isn’t guaranteed.

“In a seasonal business,” says Amber Arnett-Bequeaith, VP of Full Moon Productions, which owns three haunted houses in Kansas City, Missouri, “you are gambling your livelihood every single year.”

The rise of the haunted house

Arnett-Bequeaith’s family was obsessed with haunts. In the mid-1970s, they opened one of the first commercial haunted houses in the country, in Kansas City.

At the time, haunted houses operated as charities, sponsored by local chapters of the March of Dimes or the United States Junior Chamber. Some included quality frights, but Full Moon Productions attempted something on a larger scale.

The family leased a building downtown, which was hollowed out by a suburban exodus and rife with cheap, abandoned properties. There, they built a multi-story haunt called the Edge of Hell.

Arnett-Bequeaith, then a child, helped by sprinkling dead flowers plucked from graveyards to create a decaying scent. Customers traveled through heaven and hell, their journey culminating with a slide back into the arms of the devil. One year, the Edge of Hell brought in a live cougar — on a leash — to scare the crowds, until the city intervened.

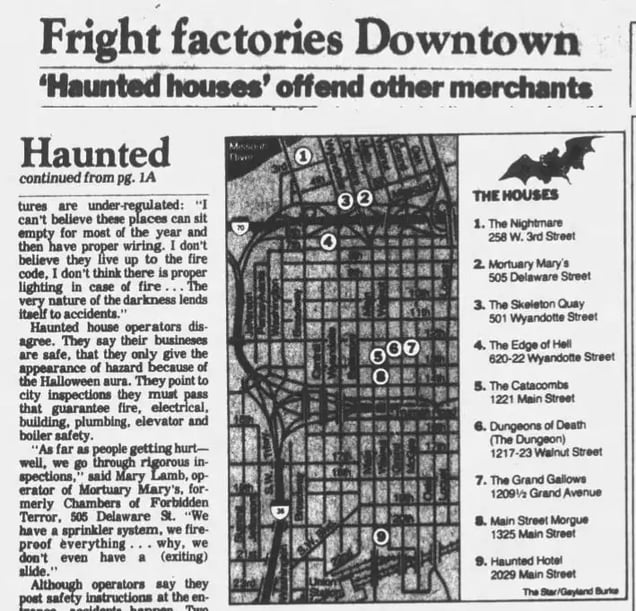

In 1982, downtown Kansas City had nine haunted houses within 20 blocks and was recognized as the haunted-house capital of the US. (Kansas City Star via Newspapers.com)

Around the country, other entrepreneurs started doing the same (minus the cougar), chasing the horror-movie trends of the ’80s and evolving into a professionalized industry with an annual haunted-house convention. In the ’90s, some entrepreneurs reported doubling their investments after their first year.

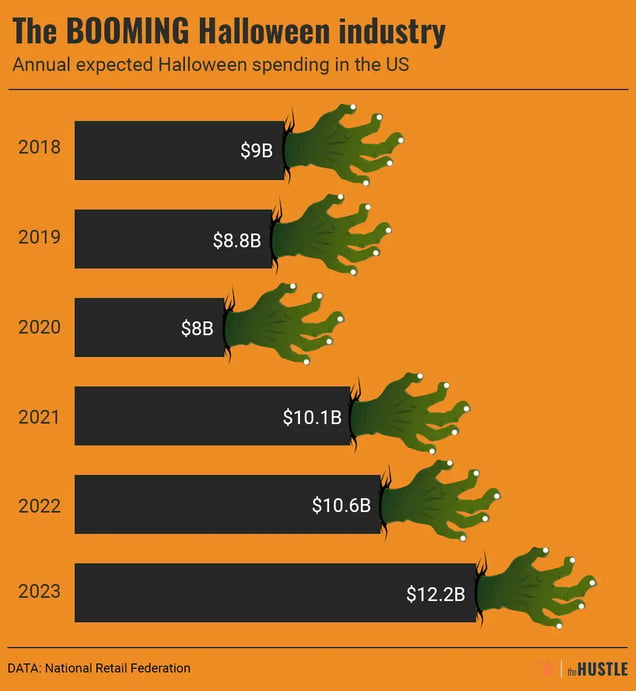

Since then, annual Halloween spending has increased from $2.5B in 1996 to $12.2B this year, with haunted attractions continuing to grow:

- Leonard Pickel, who runs the haunted-house consulting company Hauntrepreneurs, says there are now ~2x as many haunted houses in the US as there were in the ’90s.

- America Haunts, a trade association developed by the owners of the industry’s biggest haunts, estimates there are 1.2k haunted attractions that charge admission in the US and another 3k charity attractions.

- The industry, which brings in an estimated $300m to $500m annually, is dominated almost entirely by small business owners and nearly devoid of chains.

The Hustle

But despite a greater appetite for Halloween, it’s as difficult as ever to start a haunted house.

The haunted-house real estate problem

In the late 1980s, the Edge of Hell got booted from downtown Kansas City. The family decided to buy property in the nearby West Bottoms neighborhood, a livestock-oriented, postindustrial landscape that feels like a cross between David Lynch’s Eraserhead and Tombstone.

It was a fortuitous opportunity: The Edge of Hell’s new building, which happened to stand 666 feet above sea level, looked eerie on its own, and they were able to open another haunted house, called the Beast, in a second building.

Ideally, every haunted-house entrepreneur would find a scary-looking old building with a frightening backstory, says Pickel. But those situations are increasingly unlikely, especially with the cheap real estate of the ’80s and ’90s no longer available in many cities and suburbs.

Actors at the Edge of Hell. (Courtesy of Full Moon Productions)

Many new haunted houses now start on farms instead, an extension of the agritainment business. Other haunts, anywhere from one-third to one-half of all new haunted houses, according to Pickel, follow a transient model to cut costs.

These operators typically lease a shuttered building in a suburban strip mall (Spirit Halloween style) for two to three months. And while the arrangement can be cost-effective, it’s risky. Landlords may back out if they find a long-term tenant. Plus, the haunted-house operators struggle to build elaborate shows or develop a consistency of location.

Still, renting out a space on a long-term lease, even if it’s a basement or upper floor that’s relatively cheap and undesirable, requires paying a huge expense long after Halloween ends.

“You’re only making money for a month,” says Ben Armstrong, co-founder of Netherworld, the Atlanta-area haunted house that’s one of the best known in the country. “The rest of the year you’re just spending money.”

A primordial earth creature at Netherworld. (Courtesy of Netherworld)

Ultimately, size and price limit large haunted houses from taking root in prime locations of expensive coastal cities. Washington, DC, doesn’t have a single haunted house, according to The Scare Factor’s haunted-house directory. Per capita, states like Ohio, Kentucky, and Missouri have more than 3x as many as California.

Even when aspiring haunted-house operators find an optimal location, they tend to make common mistakes, according to Pickel, who sometimes consults for clients who never open their haunted houses.

- Poor budgeting: An average haunted house costs ~$250k to start ($30-$40 per square foot to build out, $2-$3 a person for customer acquisition cost, plus rent and other expenses) and usually requires reserves or new investments to keep going after the first year.

- Providing an inadequate experience: To turn a profit, Pickel says, a haunted house likely needs the capacity to accommodate as much as 500-1k people per hour, all while including twists and turns that ensure customers can’t see too far ahead and have their experience spoiled.

- Forgetting about compliance: Owners who don’t consult with city officials before building a haunted house sometimes get shut down because of code violations.

Another hurdle: Banks rarely offer loans for haunted houses, so wannabe owners need devoted investors.

In Des Moines, Miller started the Slaughterhouse in a temporary space on a short lease. He survived by accumulating free or cheap props and costumes, and closed for a couple seasons until he secured a deal with a landlord to lease a permanent space where he could reinvest profits and grow.

The Hustle

The Slaughterhouse now sees ~13k customers per year, putting it in the upper echelons of haunted houses. According to America Haunts, the vast majority of haunted attractions draw between 7.5k-10k customers every autumn. Around 1%-2%, draw more than 40k customers.

And even for the biggest players, the industry remains risky.

Inside the frightening financials

In the 1990s, a man opened a creepy motel on a farm outside Philadelphia.

Randy Bates (no relation to Norman) was no Halloween obsessive. But he was a serial entrepreneur, paying for college by repairing VCRs and later launching a security alarm business

When a nearby farmer closed a haunted hayride, he made his own version on his family farm. Five years later, after growing his hayride to ~15k customers, he built the Bates Motel, a haunted house, for ~$25k.

On busy weekend nights, the Bates Motel draws several thousand customers who pay $45-$50 for a combined entry to his haunted house, hayride, and haunted trail. Last year, total attendance was ~60k, a record.

Bates has an ideal setup. He doesn’t owe any rent and has built up an email list of 162k addresses, giving him a marketing edge as the power of traditional media fades.

Yet, Bates says, every year “can be scary.” His annual operating costs total ~$1.2m, including:

- Wages for 340 seasonal employees, which make up the bulk of his expenses.

- New props, sets, and add-ons, which can cost ~$200k-$300k, including labor. Bates’ employees make some props, others are purchased. (Fake blood and makeup — absolute musts for any haunted house — total $6.5k.)

- Insurance, which costs ~$50k and is necessary for, among other things, dealing with lawsuits.

The Hustle

To pay off those expenses, cover salaries of several full-time employees, and make enough profit for him and his wife, Bates says he likes to make about $2.5m.

Most years, the revenues from the haunted attractions dry up by April or May, leading Bates to seek a line of credit to maintain payroll. Recently, he’s taken out a line of ~$75k, but in the past he’s needed as much as ~$500k, putting him in a precarious position every time he starts anew in the fall.

“We used to be really nervous about it,” Bates says. “Fifteen years ago, I’m talking to my accountant, I’m like, ‘Oh man, I hope we can make our money back.’”

Success is still hardly a guarantee. A year’s worth of preparation and expenses comes down to a few weekends, and, just like in farming, an anticipated profit can be upended by circumstances outside of an owner’s control, including rainy weekends that reduce visitors at haunted houses and decimate outdoor mazes and hayrides, or a brief economic downturn hitting at exactly the wrong time.

Other entertainment options can also be disruptions. When local Major League Baseball teams make deep postseason runs, area haunted houses often struggle as would-be customers go to games or watch baseball at local bars.

To minimize risk, Bates has branched out into other ventures, like operating a Christmas tree farm and developing a Groupon-esque coupon platform solely for haunted houses. (He hopes to introduce it nationwide.)

Miller plans to open a speakeasy with a haunted theme in Des Moines, and many haunted house owners operate escape rooms.

Amber Arnett-Bequeaith, who’s known in the industry as the Queen of Haunts. (Courtesy of Full Moon Productions)

In Kansas City, Arnett-Bequeaith’s family bought up other cheap properties in the West Bottoms and now uses them for festivals and leases them out to other businesses, helping to jump-start the area’s revival and bring them offseason income. Chef J, one of the city’s most popular barbecue joints, operates out of the same building as the Beast.

Arnett-Bequeaith says the extra real estate helped them survive. She considers their haunted houses to be dramas that bond people together, coming-of-age stories with extreme lows and highs — not unlike owning a haunted house.

“Yes, there are screams,” she says. “But it’s always followed by laughter.”