If you listen to Spotify’s music recommendations, there’s a good chance you’ve come across songs by Sadie Dupuis.

As Dupuis told The Hustle, she’s been on the cover of 4 Spotify-curated playlists at the same time. But while the coveted spots on the playlists may have led to greater exposure, they did not lead to greater riches.

She recalls making more money from lesser-known music sites like Bandcamp in a month than she does from Spotify in a year.

“I don’t know any artists who feel their career has been made better by Spotify,” said Dupuis, who has accumulated more than 15m Spotify streams as solo act Sad13 and as a singer and guitarist in Speedy Ortiz.

Sadie Dupuis advocates for musicians as an organizing committee member for the Union of Musicians and Allied Workers. (Via Carpark Records)

Spotify, the world’s leading music streaming platform, has been heralded as the savior of the recording industry.

But it sure doesn’t feel that way right now.

When famed rocker Neil Young demanded his music be removed from Spotify over Joe Rogan’s publicizing of covid misinformation, he was joined in his protest by dozens of other musicians. The debacle added fire to a long-simmering dispute over the platform’s inequitable economics for creators.

Spotify just announced it pulled in ~$11B in revenue in 2021. Yet artists — from major stars to indie musicians — feel they aren’t getting their fair share of the pie.

“Spotify is built on the back of music streaming,” said singer India.Arie in an Instagram post showing multiple clips of Rogan saying the n-word on his podcast. “So they take this money that’s built from streaming and they pay this guy $100m, but they pay us (a fraction) of a penny.”

How does Spotify function as a business? Why are artists so poorly compensated on the platform? And will Spotify survive if it continues to alienate them?

The deal that made Spotify a juggernaut

When serial entrepreneur Daniel Ek co-founded Spotify in 2006, people had 3 main options for listening to recorded music:

- Paying $10-$15 for a digital or physical album

- Paying $1 for a digital song

- Illegally downloading albums/songs for free using a file-sharing service like LimeWire

The latter option was becoming more and more popular — and it was putting the recording industry in a bind.

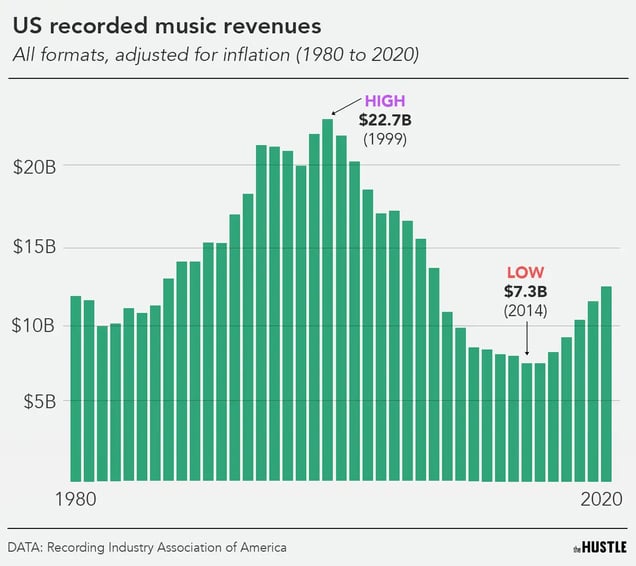

Annual recorded music revenues had fallen from an inflation-adjusted peak of $22.7B in 1999 to $15.1B in 2006. By 2014, that figure had sunk to just $7.3B, per the Recording Industry Association of America.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

Spotify offered an in-between option: all the music you could illegally download on a file-sharing service but available to legally stream at a monthly cost or on a free ad-supported tier.

Today, the platform is a behemoth:

- It has 406m users (180m of whom are paid users).

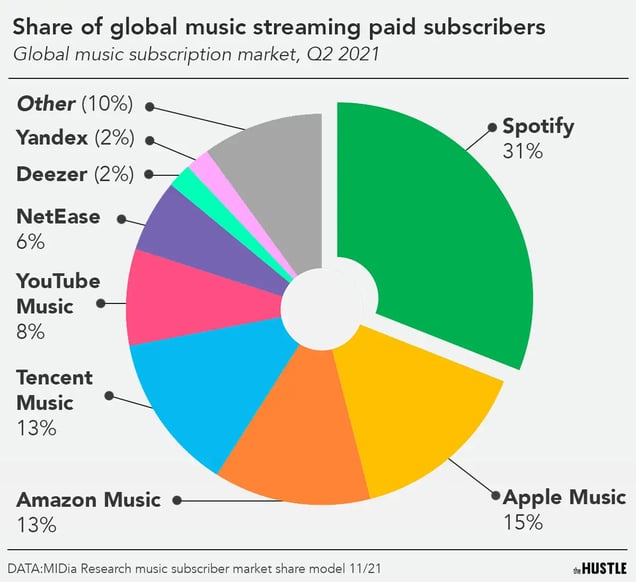

- It accounts for 20% of all recorded music revenue, and towers above competitors like Apple, Amazon, and Tidal.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

To reach these heights, Spotify had to negotiate with the music industry, which had sued many previous ‘disruptors’ out of existence. But with Spotify, industry leaders made a deal ahead of its 2011 US debut:

- The biggest labels, including Warner Music Group, Sony, and Universal Music Group, received a combined 18% ownership stake in Spotify, netting them hundreds of millions of dollars.

- Spotify set up a royalty payment structure, sending ~67% of revenues from music back to music rights holders. In 2020, this share of revenues was ~$5.7B.

That royalty structure is further divided between recording rights (held by labels and artists) and publishing rights (held by music publishers and songwriters). Exact details for these agreements vary and are rarely publicly revealed, but Spotify has said major labels get ~50%-52% of total revenues while publishers get ~15%-20%.

With streaming and Spotify soaring in popularity, the record industry has seen revenues increase every year since 2015, to $12.2B in 2020. The growth was enough for Fortune to proclaim, in 2019, that “Spotify saved the music industry.”

But the economics of Spotify have kept at least one group from feeling salvation: artists.

How Spotify payouts really work

As musicians called for more economic transparency from Spotify last year, Ek stated that the platform’s goal was to help musicians make a living.

“It’s something we take seriously every day,” he said in a press release.

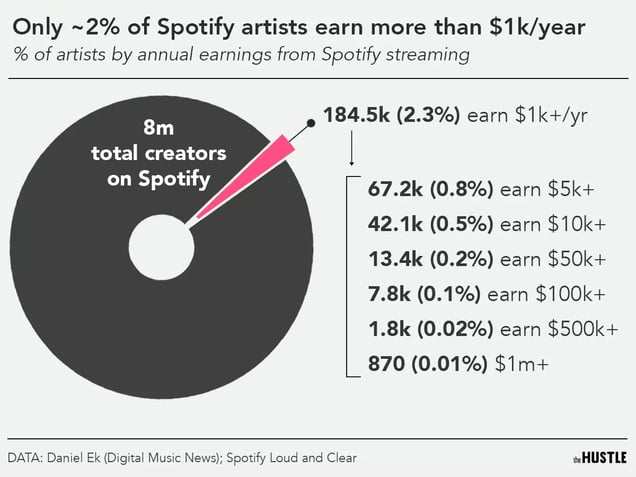

In the last few years, the number of musicians making money on the platform has grown. But in 2020 the number of recording artists whose catalogs generated $50k or more on Spotify was just 13k. That’s out of ~8m “creators” on the platform in 2020.

If these royalties make it back to the artists, they find their payout is usually a fraction of a penny per stream.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

How does this payback system function, and why is it so unsatisfactory for artists?

The dollar amounts of royalties are complex and involve things like:

- The rights holders’ deal with Spotify

- The location of the users streaming the songs

- The total revenue Spotify brought in that month

- The total number of streams that month

But basically, as royalty collections executive Jeff Price explains, the total sum that goes back to rights holders each month is based on the proportion of overall streams the rights holders’ streams represent that month and the cut of music revenues the rights holders have negotiated with Spotify.

A rough payout structure would look something like this:

The Hustle

Those variables, added up, lead to a small number for most artists, especially those who are not stars and may have a less favorable deal with Spotify.

The music blog The Trichordist has shared a midsized independent label’s payout rates for the last several years, finding its average per-stream payout has declined to just $0.00348 as the service has expanded into more countries and extended more subscription discounts and bundles, and as users streamed more and more songs.

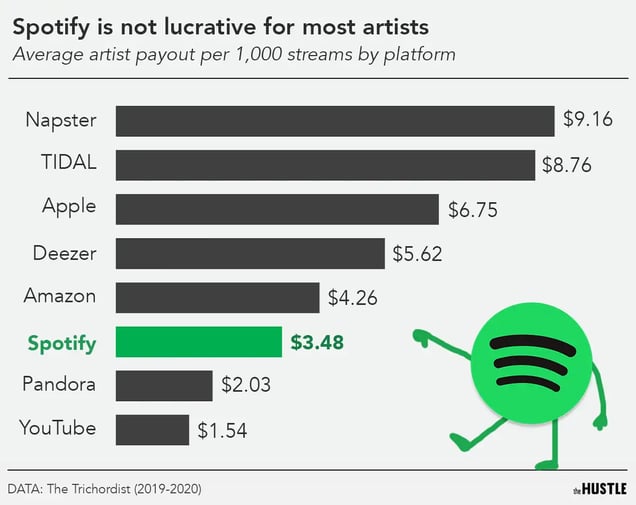

Although Spotify has the biggest user base and largest revenues from streaming, its average payout rates work out to be among the lowest. Napster’s and Tidal’s payouts average more than 1 cent per stream, according to estimates from Digital Music News and The Trichordist.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

The ⅓ of a cent doesn’t filter directly to the artists, either.

With radio, artists typically split royalties with labels 50/50. But with streaming their payment depends on their agreement with their label.

Some artists own the rights to their catalog and get almost everything. For most, the amount is far less. Kanye West once posted documents showing he received 14%-25% of the revenues sent back to his label from streaming.

Others get nothing.

“Our stupid band gets close to a million monthly streams on Spotify. Spotify pays out .003 cents per stream,” Eve6 frontman Max Collins, who regularly criticizes Spotify, said on Twitter last week. “100% of that goes to our former label Sony, who is a part owner of Spotify.”

This micropayment structure is different from what the recording industry experienced a generation ago.

When somebody bought a CD in 1999, they were essentially paying an upfront cost for a lifetime of listening, according to Eric Drott, a professor at the University of Texas at Austin’s Butler School of Music.

That cost is now being split up over months, years, and decades, each time somebody streams a song.

Giant record labels like Sony, which are conglomerations of many other record labels, have such a huge portfolio of artists and songs that the micropayments add up to a lot of money. Private equity firms that have purchased music catalogs have also found the structure appealing.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

That’s not the case for artists.

“(Artists) may get paid the same amount over the course of a lifetime as maybe an album would generate in the first six months it’s released. But it’s being spread out over a lifetime,” Drott said. “If you spread a little pat of butter over toast too thin it doesn’t add too much to it.”

Why Spotify won’t increase payouts

At a music industry conference in 2019, singer and composer Ashley Jana asked former Spotify executive Jim Anderson a question on the minds of many of her peers: Why couldn’t Spotify pay more, perhaps increasing its per-stream payouts to rights holders to 1 cent?

“Do you guys want to talk about entitlement now?” Anderson asked.

Anderson went on to say Spotify was created to solve the problem of piracy, not “to pay people money.” To Jana, it was emblematic of what she views as a lack of interest from Spotify in benefiting artists, not just with greater royalty payments but other means of increasing compensation opportunities for artists on the platform.

“They’re almost antagonizing musicians,” Jana told The Hustle. “They’re not even a neutral company. They seem to go out of their way to shoot at musicians one way or the other.”

It would be difficult to guarantee a 1 cent payout per stream given the complexity of Spotify’s payout system.

But Spotify, which did not respond to an interview request, could address this in a number of ways.

- Increase the size of the royalty pool by increasing the share of revenues sent back to rights holders (music service Bandcamp pays back 80%-90%) or tapping into other reserves of cash.

- Instead of negotiating royalty rates with every label, it could also pay back a flat rate, as Apple does, aiding independent musicians such as Jana, who likely receive lower rates than big labels.

- Another option would be switching to a user-centric payment system that would compensate artists based on their proportion of streams of each individual who streams them, rather than as a proportion of all streams in a monthly period.

Daniel Ek, CEO of Spotify, gestures as he makes a speech at a press conference in Tokyo in 2016. (TORU YAMANAKA/AFP via Getty Images)

Major changes are probably not coming, according to Drott, the University of Texas professor.

Spotify has yet to turn steady profits and is still trying to expand to control the streaming market. Sharing more revenues would limit its ability to invest, and a price hike would send users to rivals Amazon and Apple.

Spotify might face greater pressure to change — both its payouts to rights holders and the way it handles its controversial podcasts — if it directly dealt with more influential artists.

Aside from independent acts who have less clout and a few major performers who own their rights (even Neil Young doesn’t own his rights), Spotify does business with the giant record labels who have profited heavily from the company and still own shares in it.

And what about podcasting?

Spotify has also embarked on a trajectory that may dilute the labels’ influence.

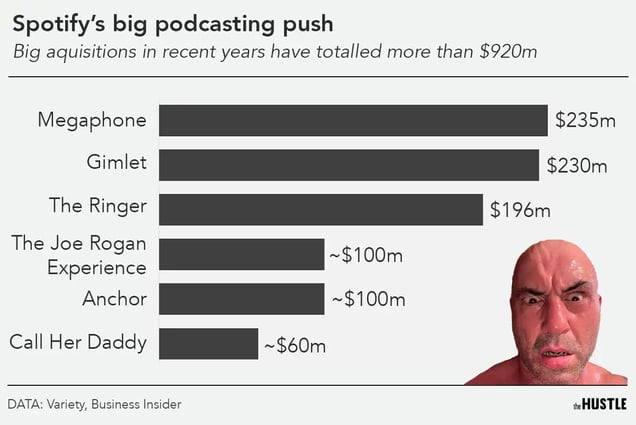

Since emphasizing podcasting and buying the rights to Rogan’s show, The Ringer, Gimlet, and ad-hosting platforms Anchor and Megaphone, Spotify’s share of revenue tied to ad dollars has risen.

In Q2 2021, podcasting revenue was up 627% YoY, and podcasting is the main driver for why Spotify’s Q4 2021 revenue share from ads reached a record 15%. Ek has said that share could rise to 30%-40% in the next 5-10 years.

The Hustle / Zachary Crockett

The economics of podcasting are more straightforward.

Spotify takes in every ad dollar for the podcast properties it owns, and podcasters using Anchor and Megaphone can allow Spotify to assist in monetization and take up to 50% of the ad revenue, according to Bryan Barletta, who curates the “Sounds Profitable” podcasting adtech newsletter.

And there’s another built-in advantage for Spotify when it comes to podcasters: The company doesn’t owe them royalties with every stream. Nor does it have to worry about them voicing concerns over royalties, like musicians.

Dupuis, the singer and guitarist of Speedy Ortiz, has been outspoken about the platform for a couple years now.

She has noticed that her once-prominent positioning on Spotify has dropped considerably from the days when she says she was the face of 4 curated playlists simultaneously.

“I started to gripe a bit,” Dupuis said, “and have not been playlisted since.”

Disclosure: Bryan Barletta’s podcast has received sponsorship money from HubSpot, parent company of The Hustle.