“Worst since 2008.”

It’s a phrase we’ve seen a lot of in recent weeks, as COVID-19 continues to claim lives and shutter vast swaths of the economy. We’ve seen the volatile stocks, the 16m+ unemployment claims, and the double-digit GDP drop projections. Some anticipate a crisis “deeper and more severe” than the Great Recession.

The situation we’re in now is fundamentally different: It’s the result of an external factor, not financial vulnerabilities — and our ability to “reopen” thousands of businesses hinges on controlling a virus.

But most crises share certain commonalities and universal lessons.

As thousands of entrepreneurs sit at a standstill, we thought it might be helpful to glean some encouragement from those who made it through tough times in the past.

Last week, we sent out a survey and received more than 200 responses from small business owners who survived the Great Recession. We’ll highlight a few of these stories in this article, focusing on the range of strategies that were employed.

But first, a few bigger-picture takeaways

The average small business in our survey was around 8 years old and had 16 employees at the time of the 2008 recession.

We heard from folks all over the world, in a wide range of industries: A cattle rancher in California, a boat builder in New Zealand, a crab shack owner in New Jersey, a hedge fund manager in New York, a family physician in Tennessee. Some companies had 2 employees; others had more than 100.

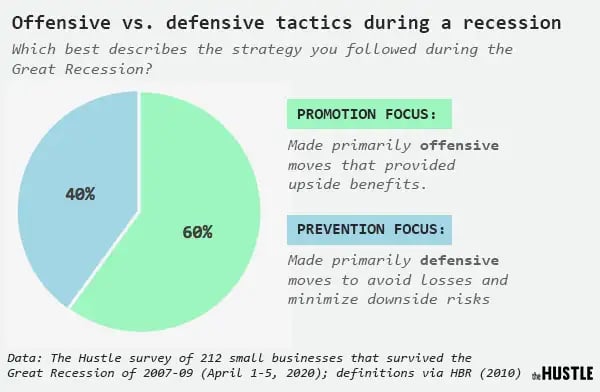

The businesses we surveyed weathered the Great Recession by adhering to one of two overarching approaches:

- Promotion focus: They made primarily offensive moves that provided upside benefits.

- Prevention focus: They made primarily defensive moves to avoid losses and minimize downside risks.

Among our sample, businesses leaned slightly toward offensive (e.g., expansion) over defensive (aggressive cost-cutting) strategies.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

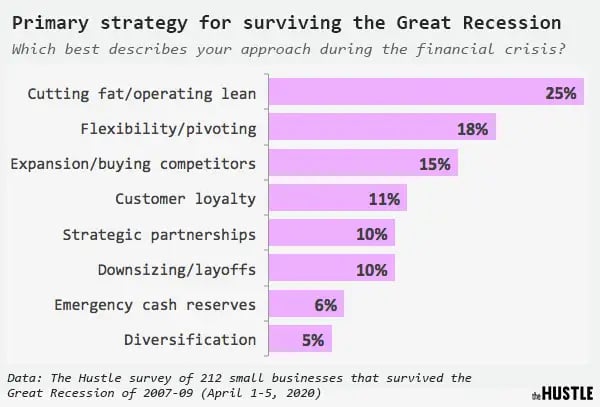

Breaking this down on a more granular level, there was no magical, universal path to survival. What worked for a gardening store in Iowa wasn’t necessarily the best bet for a travel agency in Florida.

Successful business owners employed a variety of strategies to make ends meet, from entering into strategic partnerships to significantly downsizing staff.

Zachary Crockett / The Hustle

When small business owners faced dramatic downward shifts in revenue, they had to get creative and, in some cases, make extremely difficult decisions:

- Rhys Williamson’s fiberglass boat business saw sales decline from $3m to $150k/year; he survived by pivoting to specialized repair work.

- Robert Radcliff’s consulting firm business took a tumble from $1.8m to $550k/year; he had to lay off his entire staff to make ends meet.

- Dida Clifton’s virtual bookkeeping company lost 50% of its business; she survived by forging strategic partnerships.

- David Stringer’s SaaS for auto accessories business lost 37% of its revenue; he stayed afloat by diversifying his client pool.

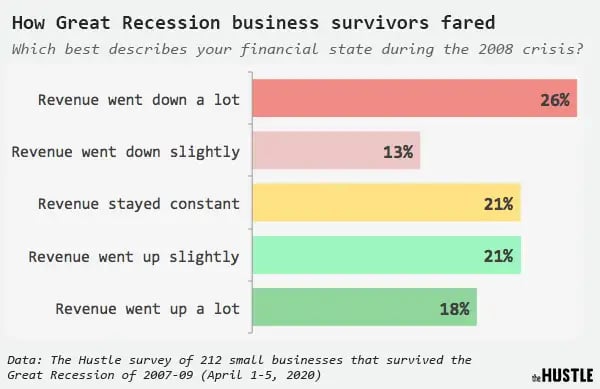

Small businesses survived the Great Recession in various financial states. Some thrived, and saw revenue go up; others hung on for dear life.

(Zachary Crockett / The Hustle)

One unifier between these stories and those that are sure to come out of COVID-19 is that crises put a strain on everyone — even those who find success.

Andrew Russell, of the Scotland-based body and fragrance company, Arran, told us he lost 42 pounds in 3 months. We heard from other business owners who lost their spouses, their homes, and their friends due to the financial pressures of the Great Recession.

Around 1.8m small businesses went bust between December 2008 and December 2010. But below, we’ll focus on the journeys of 5 entrepreneurs who made it through.

The creative agency owner

Ernest Montgomery cut every cost he could think of — including his own residency in the US (Photo courtesy of Mr. Montgomery)

In 1996, Ernest Montgomery, a then-24-year-old photographer in New York City, wasn’t getting along with his boss.

So, the NYU grad quit his job and launched The Montgomery Group Represents, a creative agency that produces editorial and advertising campaigns and manages its own talent (photographers, stylists, makeup artists) in-house.

For the next decade, Montgomery enjoyed modest success, booking clients like American Airlines, Pepsi, and The Miller Brewing Company. He rented a beautiful office on 7th Avenue in Manhattan, expanded his staff to 15 artists, and grew his revenue to around $800k/year.

But toward the tail end of 2008, Montgomery began to lose a lot of business.

“Clients were saying, ‘Look, we can’t pay you $25k for this video. We can give you $5k — and all the costs will have to come out of your pocket,’” he recalls. “The question was: Do I want to work and make something, or sit on my pride and wait for the good times to come back?”

Montgomery chose the former, and cut every single expense he could think of:

- He left his $4.2k/month office, went “virtual,” and made his entire staff remote

- He axed his web design budget and learned how to build sites himself

- He stopped running expensive ads in industry publications and started dropping off physical copies of his portfolio to prospective clients

- Most dramatically, he permanently relocated to the Dominican Republic

“A campaign that costs $100k to produce in Miami can be made for $65k in the Dominican Republic,” he says. “A location that costs $10k in Miami costs $500 here — and there is so much less red tape — street permits, blocking off traffic, all that.”

When the economy began to pick back up again, Montgomery found that many of his bloated competitors had gone out of business. Even in brighter times, he stayed lean.

Now 48, he continues to operate from the Dominican Republic. When he needs to meet with a client in NYC, he boards the first flight of the morning — a 3-hour journey — visits with talent, spends the whole day in the city, and takes the last flight home. “Some clients don’t even realize I live out of the country,” he says.

These extreme sacrifices have made it easier for him to weather the current crisis.

His advice to entrepreneurs in crisis: “We’re all very nervous and don’t know what will happen. It’s a good time to ask your clients, employees, and associates 3 questions: 1) What can we do to make things feel better? 2) How can we plan on surviving this as a group? And, 3) What are we going to do differently once this is over?”

The machinist

Brad Emerson with a tractor he purchased in 2017 (Photo courtesy of Mr. Emerson)

Brad Emerson, of St. Louis, Missouri, also knows a thing or two about cutting costs.

After many years of “living like a rockstar” as a salesman for a Switzerland-based machinery firm, Emerson decided to branch out on his own in 2005. The company he created, FixYourOwnBindery.com, specializes in chopping up, fixing, and relocating niche bindery machines — many of which aren’t made anymore — in printing factories.

“I was working 20 hours a week, making $250k [annually],” he says, of his first few years in business. “It was like picking up money off the street. Hardly anyone else knew how to work with those old machines.”

When the crash hit, Emerson lost 90% of his business. In short order, he went from getting 5-6 bids per day to 2 bids per month.

He shut off the lights and ate bologna for months on end. He started cutting grass on the weekends for cash. His 20-hour weeks turned into 80-hour weeks. His wife left him. At times, he struggled to feed his 3 daughters.

One day, he called his landlord and told him he was going to go out of business and miss rent. The landlord told him to bring over his bank statements and bills.

“He sat down with me and went through all of my expenses with a red pen, crossing things out — ‘You don’t need this, this, this,’” says Emerson. “That man helped me save my business.”

In total, Emerson cut expenses that totaled $3k/month, including:

- Monthly computer and software costs

- Routine maintenance on company vehicles and forklifts

- Building services, like lawn care and snow removal

- Air conditioning during the summer

With leaner overhead, Emerson decided to “follow where the market took the business.”

Printing factories were closing around the country and the industry was consolidating. A few years earlier, he’d purchased an 18-wheeler on eBay for $12k. He began transporting machinery between factories and his bids eventually began to pick back up.

He never returned to the glory days of his income, but he’s “comfortable” now, with a healthy backlog of bids. He sees himself in the struggle of today’s business owners.

“There’s a restaurant near me where the owner is running the food out to cars on the street, with the skeleton kitchen crew inside,” he says. “They’re doing it just like I was: Shaving costs as low as possible, rolling up their sleeves, and fighting to stay alive.”

His advice to entrepreneurs in crisis: “Make the painful list of every expense you have and get the red pen out. And when you push through and make those changes, don’t fall out of that mindset. Keep yourself poised for an uncertain future.”

The florist

Nic Faitos at his flower shop in the Chelsea neighborhood of Manhattan, NYC (Photo courtesy of Mr. Faitos)

For Nic Faitos, the path to flowers began as a ponytail rebellion.

In 1994, he was working as a stockbroker on Wall Street — a position that required him to wear a suit every day and barred him from growing out his flowing mane. At the time, his wife ran a small flower shop in a low-traffic bedroom community on Long Island.

Faitos began to study the retail landscape for flowers in NYC and spotted a gaping opportunity in the B2B space: “Fortune 500 companies needed flowers for their offices and employees,” he says. “But most flower people couldn’t make a spreadsheet to save their lives. These businesses wanted someone who spoke their language.”

So, he launched Starbright Floral Design, cold-called HR departments all over the city, and established himself as NYC’s go-to corporate flower source by the end of the ‘90s.

When the recession hit, many of his clients — Ernst & Young, Deloitte, Chase, hoteliers and restaurateurs — aggressively cut costs. Flowers were one of the first things to go. But Faitos, who’d been through 9-11 and the dot-com bubble, didn’t panic.

“In a crisis, the typical reflex of a small business owner is to pull back into his shell like a turtle,” he says. “But times of trouble are when marketing opportunities are created.”

He decided to go hard on marketing, offering reduced prices with the goal of doubling his client base. Faitos and staff expanded their demographic, placing hundreds of cold calls to labor unions, pharmaceutical firms, and other “recession-proof” industries.

“When you have five people on the phone and you are making about 50 calls each for an entire year, you are bound to open some new doors,” he says. “It is the way commerce in this country was built and we went back to the very basics.”

His logic was this: If you have 100 accounts spending $100 on average and all of a sudden it drops to $80, that’s a 20% loss. If you go out and develop 50 new accounts during that time, the 50% growth offsets the loss.

It wasn’t a small gamble. His product cost was around 30% of revenue and his 20 employees ate up another 30%. After factoring in the $25k/month rent for his Chelsea shop, margins were thin.

The move eventually paid off. When the economy picked back up, the new clients he’d sourced went back to paying the regular rates. In the 12 years since the recession, Starbright has doubled its annual gross revenue from $3m to $6m.

Now 62, Faitos finds himself in the midst of another crisis — and this time, business is completely shut down. But he’s back at it with another marketing strategy. On his website, he’s selling “virtual” bouquets for $70-$400: A recipient gets a photo of their bouquet via email now, and the real deal once the floral delivery ban is lifted.

Revenue is a small fraction of what it was, but he remains optimistic.

His advice to entrepreneurs in crisis: “Don’t hide! This is a time to showcase your brand and maintain relevancy. This will not last forever. The key is to take advantage of the downtime to build systems and name recognition.”

The car dealer

Dave McFadden at his Chevrolet dealership in Hoopeston, Illinois (Photo courtesy of Mr. McFadden)

Dave McFadden had always dreamed of owning his own dealership.

He served 7 years in the US Air Force straight out of high school, then took a job as a car salesman and worked his way up the management chain. In 1996, he moved to Hoopeston, Illinois — a small town of 5k — and spent the next 12 years as the general manager of Anthem Chevrolet Buick. When the owner retired, he took his shot.

“I’d spend so long saving to buy the store,” he says. “When the time came, I put every penny I had into it. I was all-in.” He finalized the paperwork on April 1, 2008.

Three months later, gas prices were up to $4/gallon. When the recession set in, the auto industry was among its worst victims: Sales volume on new cars declined 40%, and auto-industry employment fell 45% nationally. In 2009, Chrysler and General Motors filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection.

“Like any small business owner, I had a model in my head of how I was going to run things,” he says. “Suddenly, everything had fallen by the wayside.”

McFadden knew that in order to protect his business and its 18 employees, he had to focus on things that were within his control, and trust his instincts. Early on, he noticed that used car sales were plummeting. Many dealers panicked and stayed away from the used market — but McFadden saw an opportunity to expand.

“The auctions were ripe and it was a buyer’s market,” he says. “So, I doubled down on my inventory.”

It was a decision that saved his business: Many consumers still needed cars but didn’t have the means to buy new; McFadden was able to offer them a better deal than they could find elsewhere, and he offset the smaller margins on his sales by moving large volumes.

In the face of a new crisis, McFadden has employed a similar tactic: His sales floor is closed, but his service department — which accounts for 40% of his revenue — is still open. Though service work is currently down 50%, he’s at work making sure essential workers have a place to service their vehicles.

His advice to entrepreneurs in crisis: “During a crisis, a lot of things are out of your control. Focus solely on what you can control. The objective during a crisis isn’t just to survive; it’s to come out stronger.”

The furniture makers

Mary Ann Hesseldenz and Scott Baker at their Tucson workshop (Courtesy of Ms. Hesseldenz and Mr. Baker)

When Scott Baker met Mary Ann Hesseldenz at a furniture fair in 2006, it wasn’t just love at first sight; it was the beginning of a promising business partnership.

Baker had been building high-end furniture since college; Hesseldenz had worked in fashion design for 20 years in New York. They married, settled in Tucson, Arizona, and launched Baker Hesseldenz Studio, a boutique interior design firm that makes custom luxury furniture.

The business catered to a wealthy clientele who were building new homes and wanted a $17,641 couch, or a $22,137 curio, or a $5,290 cocktail table.

But when the recession tanked the housing market, the couple had to recalibrate.

They noticed that, while wealthy people weren’t building new homes, there was still a thriving remodeling market. So, they decided to pivot from high-end furniture to millwork and cabinets — a far cry from the craftsman work they were used to.

“Many of the large cabinet makers in Tucson went under because they had too much overhead,” says Baker. “We were small and had always prided ourselves on running a very lean operation — no $500k CNC machines or giant shop.”

Tucson’s low cost of living was key to the couple’s low overhead: His 2.6k sq. ft. warehouse was $1,150/month (a mere $0.45/sq. ft.), and skilled labor could be found for $12-15/hr. When they needed extra workers, they hired independent contractors.

During the recession, the couple says the company’s revenue actually went up.

Pre-recession, selling mostly furniture, they grossed $250k; in 2009, they grossed $300k on just a few millwork jobs. A single kitchen remodel would net them $30k-$50k.

Though Baken and Hesseldenz eventually returned to higher-end furniture after the recession cleared, cabinetwork is currently saving them again: In Arizona, furnituremakers are closed for business but residential construction — including cabinet work — is considered essential.

A decade later, they’re up to $1m in gross revenue: $500k in millwork, $300k in furniture sales, and $180k in interior design fees.

“The cabinets are allowing us to keep working,” says Hesseldenz. “That pivot years ago is saving us again.”

Their advice to entrepreneurs in crisis: “The biggest thing we learned is how important it is to run a very lean operation. Do not over-hire or get yourself locked into expensive recurring costs. Resist the urge to overspend during the good times.”

***

NOTE 1: We’ve compiled more than 200 stories of small businesses that survived the Great Recession, along with advice they have to offer on the current crisis. You can access the full database, along with revenue figures on 800+ other small businesses, by signing up for a Trends trial here.

NOTE 2: If you need help navigating the $349B small business relief package, or figuring out how to apply for a loan, check out our CARES Act guide here.