Several months ago, 82-year-old Marjorie Jones* decided it was high time to draft a will.

Her possessions were considerable: A $2,000,000 home on a tree-lined street in the California suburbs; some $300,000 in cash, stocks, and gold; $100,000 worth of antiques, jewelry, and porcelain clown sculptures.

She’d never had children, and her husband had passed a few years earlier. Friendships had come and gone. But her cat — he had always been loyal.

And so, Jones opted for a pet trust.

In recent decades, it has become increasingly common for people to leave their pets a chunk — or, in some cases, the entirety — of their estate. Some particularly lucky dogs, cats, and hens have even inherited fortunes in the millions.

Why is this happening? How exactly does it work? And what does it say about our changing relationship with pets?

The rise of the pet trust

Until fairly recently, animals were an afterthought in wills and trusts.

“Traditionally, you’d just give your pet to a relative or a friend,” estate attorney Benjamin Sowards tells me. “There was no thought about money, and nothing to legally enforce the quality of care.”

By the 1990s, things began to change. The animal rights movement set its sights on pet inheritance, and laws were written that made it easier for people to leave animals assets through dedicated pet trusts.

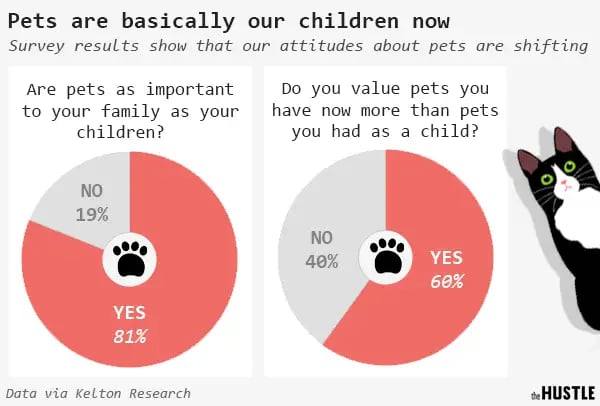

Today, 81% of pet owners say they value their pets as much as their own children. More than half prefer the term dog “parent” to dog “owner” — and 60% consider the dogs they have today to be “more important” than the dogs they had growing up.

“The days of the doghouse out in the yard are over,” says estate planning attorney, Kelly Michael. “Now, our pets are inside, next to us on the couch in the living room. They’re a part of the family.”

Simultaneously, sociological research has suggested that an increasing number of Americans are growing old without children or spouses.

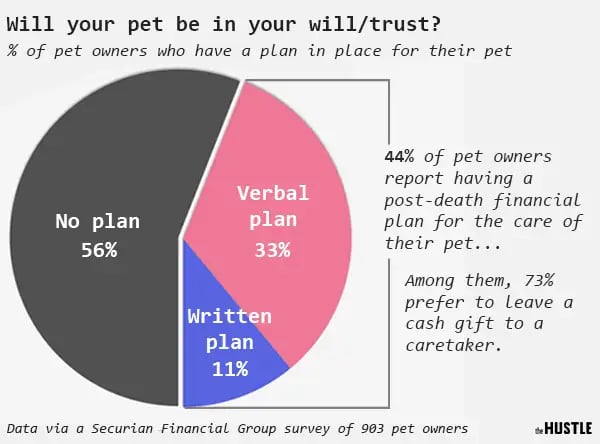

This combination of rising affection for animals and declining human companionship has been good to the pet trust industry: One survey found that 44% of pet owners have some kind of post-death financial arrangement for their pet.

In most US states, pets are considered property. This means they can’t inherit money directly — but an owner can designate a trustee and a caretaker to use the money explicitly for their pet’s benefit.

By way of legal enforcement, there are two major ways you can leave money behind to your pet: You can draft a will (a document that lays out how you want your things divvied up after you die), or establish a trust (where you name a beneficiary, then give another person or party power to delegate assets to their benefit).

“With a will, you might leave $10k to your friend to take care of your cat, but it’s just a moral obligation: If your friend wanted to, he could give the cat to a shelter and use the money to pay off his student loans,” says Michael. “With a trust, he has a legal obligation to use the money for the pet.”

How do pet trusts work?

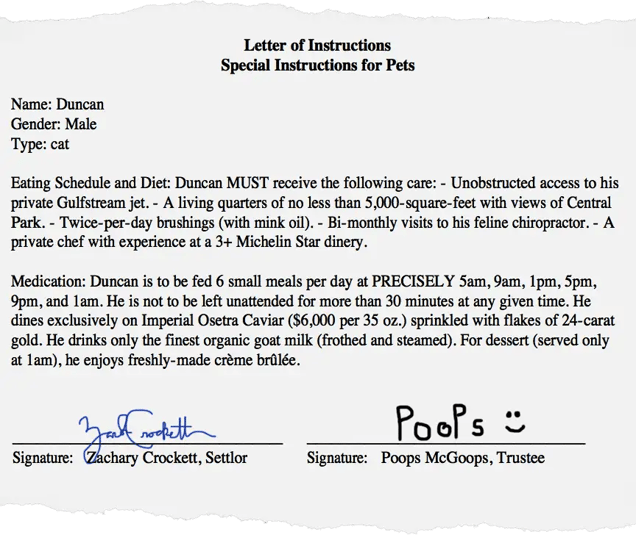

To help explain what this looks like, I created my own pet trust using one of the dozens of online legal services that offer them. [The full document can be found here.]

Let’s imagine I have $25m and I want to give it to my beloved cat, Duncan.

With a pet trust, there are a number of moving parts:

- Settlor: Person giving the trust

- Beneficiary: Party the trust is designated for

- Trustee: Person responsible for handling and overseeing the trust

- Caretaker: The person who will care for the cat in my absence

- Enforcer: The person who makes sure the money is used properly

I decide to make my trustee/caretaker my esteemed colleague, Poops McGoops.

Poops’ responsibility is to make sure my money is used to give Duncan the “lifestyle he’s accustomed to.” In his case, that includes unobstructed access to his private Gulfstream jet, a private quarters overlooking Central Park, visits to his feline chiropractor, and meals of caviar and steamed organic goat milk.

In exchange for his caretaking, I set aside a fund to pay Poops a weekly salary of $5k.

If he steps out of line at all or tries to siphon off some of Duncan’s money for his own benefit, my enforcer, Mike Tyson, will intervene. Mike will regularly check up on the trust and make sure Poops is meeting Duncan’s standards (environment, diet, exercise, vet care, grooming, medications, etc.).

What happens when Duncan dies? I’ve set up a “residual beneficiary.” Any funds left over from my trust upon his death will be donated to the esteemed Association for the Financial Freedom of Felines.

Trust issues

“I generally treat pets exactly the same as a person or child,” says Sowards, who runs an estate planning practice in Campbell, California. He says that around 10% of all his clients include a pet in their trust — double what he was seeing a few years ago.

But pet trusts, like all post-death arrangements, can get messy: Sometimes, caretakers don’t do their job; other times, they find ways to hoard the money.

“I’ve seen cases — and this is 100% against the law — where a [trustee] just does the bare minimum to take care of the pet,” he says. “They want to go as cheap as possible and take what’s left over for themselves.” In some cases, they may even be in cahoots with the enforcer or trustee.

In rare cases, caretakers who have a sweet gig (say, getting paid $80k per year to tend to a cat, while living in an estate for the duration of its life) might find “replacement cats” to take the animal’s place when it dies, keeping the ruse going for decades. One caretaker kept a ruse like this going for 25 years.

“The trust should be very descriptive about the animal,” says Michael. “Otherwise, the person could just get a series of black cats, and, you know, Fluffy lives forever.”

“People sometimes have unrealistic expectations from caregivers,” she says. “Someone might leave their 4-year-old dog and $10k to his neighbor, but that $10k probably isn’t going to come anywhere near covering the cost of that dog for the rest of its life.”

According to Rover, the average annual cost of dog ownership (including sitting, training, walking, dental care, vet bills, grooming, and food) runs $2,858 per year. Across all breeds, dogs live an average of ~11 years — so if you leave $20k and your dog outlives you by more than 4 years, you’re putting a sizable burden on a caretaker.

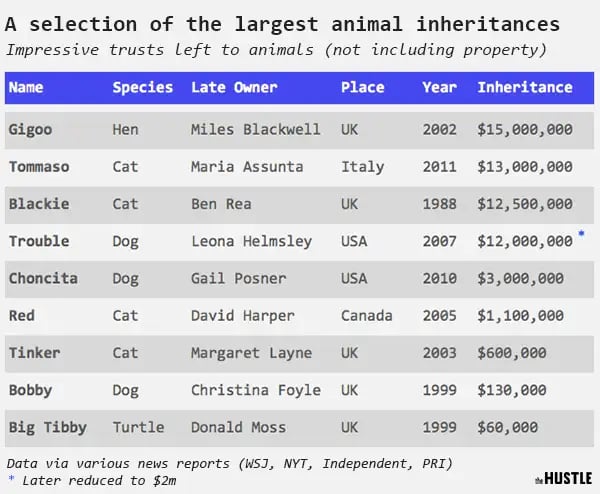

But not everyone has this problem: History provides numerous cases where owners left their pets with millions.

To my beloved tortoise, I bequeath my riches

When billionaire New York real estate tycoon, Leona Helmsley, died in 2007, she stunned the world by leaving a $12,000,000 fortune to her 9-year-old Maltese, Trouble.

Helmsley, who disdained the poor (“Only the little people pay taxes,” she’d once declared) and shunned even her own grandchildren, had earned the nickname “Queen of Mean.” The act was seen by many as a final act of defiance.

The trust was later deemed to be “excessive” in court and reduced to $2m — but the terms of the dog’s care were none the less opulent.

Totalling $190k, her annual expenses included: $100k for security (the dog received at least 20 death threats); $8,000 for grooming costs; $18k for medical expenses; $60k for her guardian’s annual salary; and meals that included “hand-fed crab cakes, cream cheese, and steamed vegetables with chicken.”

Trouble, who died in 2011, isn’t the only animal to receive red carpet care.

When Florida millionaire Gail Posner died in 2010, she left $3m — and an $8.5m mansion — to her chihuahua, Chonchita. (Her son, meanwhile, received a paltry $780k). Reportedly, the dog enjoyed a full-time staff, spa treatments, diamond-studded Cartier collars, and “custom wigs created by the Beatles’ former make-up artist.”

Though bequeathed far less, Big Tibby also enjoyed a nice retirement: The turtle was given private ceramic baths and fed a diet of “Italian selection salads.”

Miles Blackwell, a British publishing magnate and animal rights activist, made headlines in 2002 when he left his rare hen, Gigoo, a £10m fortune, and antiques tycoon Ben Rea cast aside family members in favor of Blackie, the last of his 15 cats.

“I’ve seen designer dogs get $100k per year, and I’ve seen cats get the house,” says Sowards. “Nothing is off-limits.”

These are, of course, extreme outliers — but they speak to the shifting tides of how pets are being written into our post-death plans.

At a time when the majority of all Americans don’t have any estate plan in place, and the country’s income inequality gap is the largest it’s been since the Roaring ‘20s, bequeathing riches on pets incites a special breed of anger and leads to some interesting questions about human exceptionalism.

“To give such a large sum of money to dogs generally is not frivolous,” Rutgers philosophy professor, Jeff McMahan, argued in 2008. “I think it shows some misplaced [moral] priorities, but many bequests do … [Welfare] for dogs is better than more pampering of the rich.”

Sowards has a more lawyerly take: “There’s nothing that requires you to leave anything to your family,” he says. “People should be grateful to get anything.”

Even, it seems, the leftover scraps from the pet.