Todd Westby never meant to build a global surveillance empire — he was just sick and tired of his soda machines breaking down on him.

Yet on August 1st, 2017, employees of Westby’s vending-machine business, Three Square Market, gathered around a small table at their River Falls, Wisconsin headquarters. On it were three objects: A laptop, a bowl of tortilla chips, and a hypodermic microchip implantation needle.

Dozens of cheerful Midwesterners in blue-collared company shirts had volunteered to let their employer implant tiny microchips under the skin of their left hands. The chips let employees open doors, log into computers, and pay for snacks using the company’s proprietary vending machines.

By the end of the day, 50 of the company’s 80 employees had received RFID chip implants.

According to Westby, the process felt “like somebody stepping on [your] pinky toe with a dress shoe on.” What soon came to be known as the “chip party” made headlines everywhere from The River Falls Journal to The New York Times.

But most media coverage neglected an important question: Why was a small vending machine company developing microchip tech in the first place?

A man with a taste for opportunity

Westby’s path to building a surveillance empire started with a margarita in a hot tub on vacation in Huatulco, Mexico, in 1998.

At the time, Westby worked at a 200-person student loan collections agency. But, he had an idea for a side-hustle that would give his coworkers something to snack on, and make Westby a few bucks in the process: A vending machine franchise.

Intoxicated by his entrepreneurial vision, Westby asked the waiter to bring him a calculator with his next round of tequila.

“I punch[ed] in some simple numbers,” Westby later told a business partner. “Fifty cents times 24 cans times 10 cases — and I said, ‘Wow.’”

When he got home, Westby immediately asked his boss if he could install some vending machines at work. Westby installed 50 machines in 6 months, at a cost of around $20k. Before he knew it he had incorporated his eponymous business, TW Vending.

A business built on captive audience

Business was good, but not all vending machines were created equal.

Profit margins for normal vending machines were slim. But after Westby learned that prison commissaries (jail-speak for ‘food stores’), mark up basic items like cereal as much as 5x simply because they can, he knew he had arrived at the right $1.6B market.

By aggressively courting prisons, Westby soon automated decades-old prison systems with new software for RFID vending machines, video visitation, inmate email, money management, documentation, and intra-facility communication.

“Are you ready to create efficiency and revenue for your jail?” asked TurnKey’s LinkedIn page. “Take all those extra tasks such as commissary, communications, and accounting and completely [sic] automated your jail! With TurnKey Corrections, you can!”

Between 2010 and 2017, TurnKey Corrections grew from a tiny vendor in 4 Midwestern states to a for-profit prison powerhouse across 25 states. But as the company grew into a complex prison-tech company, Westby stayed true to his roots.

Instead of assembling a team of engineering prodigies who went Stanford and Harvard, Westby picked his executives the same way he would have drafted a pickup football team.

Who did Westby choose for his CFO? His older brother, Tim. For COO? His brother-in-law, Patrick McMullan. Director of Sales? Who else but his son’s beloved high school football coach, Tony ‘Coach’ Danna.

But, as the family business grew, so did public scrutiny: TurnKey Corrections started appearing on watchlists created by human rights organizations.

As for-profit prison providers started taking heat for hiking prices, Westby began exploring new revenue streams — and the search took the company somewhere Westby couldn’t have imagined.

Hiding prisons behind playgrounds

In 2012, Westby went from CEO of a massive prison software business to CEO of a commercial IT company — at least, according to the internet.

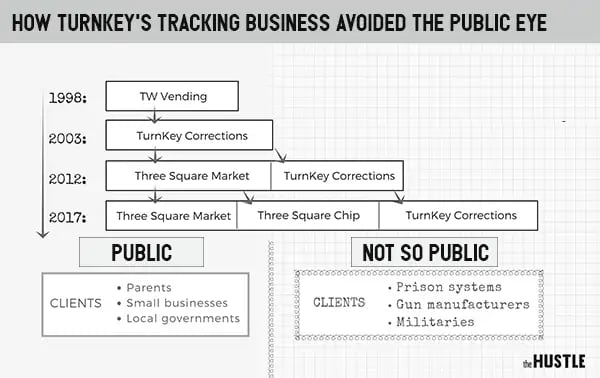

If it seems confusing, it’s meant to be. Westby’s operations all technically fall under one umbrella company, TurnKey Corrections-Three Square Market (‘TKC32M’ for short). But Westby split the company in half in 2012 to use the new Three Square Market as a smokescreen for the original, hush-hush half of the business, TurnKey Corrections.

Westby’s new public-facing brand, Three Square Market, started marketing the same smart vending machines to retail clients that TurnKey had been selling to prisons for years.

To keep things safely separate, Three Square Market’s page doesn’t disclose the company’s relationship with its prison parent company anywhere on the site.

With attention successfully diverted from the prison business, Westby and McMullan launched yet another shell company focused specifically on tracking systems, Three Square Chip.

Last month, Three Square Chip announced its first public app. The tracking app, called ‘Mom I Am OK,’ helps parents monitor children with ping notifications and geo-fences that keep kids from leaving pre-defined areas.

But, Three Square’s press release failed to mention that the new app was, in fact, already being used in 3 counties, on several thousand prisoners. (“We rolled it out last spring,” McMullan confirmed to The Hustle.)

“Why not us?”

If the last year is any indicator, employee tracking is just the tip of the iceberg.

According to McMullan, representatives from organizations ranging from foreign governments to national health insurers have requested custom surveillance solutions.

Three Square Chip plans to launch a new, body heat-powered chip featuring GPS and voice activation in 2019. Publicly, the company is developing systems for child care providers, healthcare systems, and city planners. Less publicly, it’s also building systems for prisons, gun manufacturers, and the military.

So, how did these Midwestern dads and football coaches transform a prison services company into a surveillance empire without outside funding, experienced technical expertise, or access to tech’s most elite talent?

Because there was nothing to stop them.

“We came across this [technology] and we saw it being used in other societies,” McMullan told reporters when they asked about the new chip business. “And we said, ‘why not us?’”

If Westby’s success proves anything, it’s that that digital surveillance technology is now so cheap — and so unregulated — that almost anyone can sell it.

A ‘get-rich-quick’ scheme for the age of big data

Westby’s strategy for selling sodas to inmates and selling tracking systems to parents were strikingly similar: Find a niche market and pump it with marked-up wholesale products for a huge profit.

The market for surveillance technology meets every precondition for a Grade-A get-rich-quick scheme: Cheap inventory, little regulation, and high demand.

First, surveillance tech is surprisingly cheap. According to the Yale Law Journal, the cost of location tracking dropped from $105/hour to $0.36/hour when the portable GPS was invented, and then fell to to $0.04/hour at most when smartphone GPS became roughly equivalent to professional receivers.

Using tracking technology already built into smartphones, Three Square’s new Mom I Am Ok app will cost consumers just $9 per month. A small sum to most buyers, but a huge markup on how much it will cost Westby to maintain the service.

Second, there are no rules. No federal law prohibits person-to-person location tracking, and while some states have tried to regulate digital surveillance with stalking laws, there are still very few rules for private tracking apps and the data they process.

Finally, and most importantly, tracking software is in high demand. More than 200 apps — some of which have more than 27k subscribers — use GPS and covert camera access to track people, and demand to track family members (both partners and children) is huge.

As data collection becomes more pervasive, it would seem natural that security concerns would scare off some users. But the reality is the opposite. In fact, according to research from Intuit, employees are more concerned about the battery and data costs of employers tracking their smartphones than the privacy costs.

Welcome to the IoP

“We’ve all heard of the internet of things,” McMullan told attendees of a January tech conference in Wisconsin. “Well our tradeline — and we’ve applied for a trademark — is called ‘the internet of people.’”

McMullan, Three Square’s resident dreamer, firmly believes his chips will change the world.

He told The Hustle his vision: A future where doctors detect heart attacks 12 days in advance, kids safely travel alone, Alzheimer’s patients never get lost, and Wisconsinites never accidentally shovel their driveways before the snow-plow arrives.

“Chips out there today are like McDonald’s soft serve: chocolate, vanilla, or swirl,” McMullan explained. “Our chips are like Baskin-Robbins’ 31 flavors.”

But in a world where personal data has become a valuable commodity, the childlike purity of McMullan’s vision is already melting.

When Three Square Chip launched, it advertised RFID chips as safer alternatives to GPS-enabled cell-phones. But when Westby realized the GPS-based user-tracking industry was forecast to rise from $5.8B in 2016 to $15.6B in 2020, the company quickly abandoned its resistance to GPS tracking.

Westby’s family business may be profit-forward, but it’s not malevolent (anyone who’s heard Patrick McMullan talk about healthcare and snow plows will tell you that). But customers deserve to know who is handling their data goes once it is collected.

Once an app collects consumer data, nothing prevents it from sharing with subsidiaries, parent companies, or partners.

When those partners are hidden — for instance, a quiz app that secretly collects data for a Russian political network or a childcare app operated by a for-profit prison company — consumers don’t know when they’re at risk.

And, when the companies that make and sell surveillance apps aren’t regulated, it’s even harder to ensure that the tech is used responsibly.

If we’re lucky, the future could have great snow plows. But in this new world, don’t expect control over your data and definitely don’t expect everyone who sells it to be as well-intentioned as Todd, Patrick, and Coach Danna.