Consider the restaurant menu.

By design, menus aren’t meant to spark conversation. But as restaurants take drastic steps to weather COVID-19, they are revamping their menus in a big way — and it’s hard not to think twice about the piece of paper in your hands.

IHOP is ditching its 12-page behemoth for a much cleaner 2-page menu. McDonald’s has slashed several items off its all-day breakfast menu. Applebee’s, Taco Bell, and Subway are all slimming down their offerings.

These high-profile shifts reflect what’s happening on a much more local level across the industry: 28% of restaurateurs are shrinking their menus because of the pandemic. That number is so large that New York Magazine recently asked, “Is It Time To Get Rid of Menus For Good?”

The underlying reasons for this are financial: Restaurants can’t bother with low-margin dishes. They have fewer employees on the payroll, so they want to be more efficient with a smaller set of meals. They’re prioritizing fewer — and cheaper — ingredients.

But rewriting a menu is no simple task. Every inch of text, from the typeface down to the order of items, must be workshopped for maximum profitability.

And when restaurants need help, they turn to a niche, little-known cadre of professional “menu engineers.”

When restaurant menus are the family businesses

You’d be hard-pressed to find many people who have thought more about restaurant menus than Michele Benesch.

In 1968, her grandfather, Walter Baker, started Menu Men, Inc., a creative consultancy that specializes in infusing menus with fanciful designs.

At the time, says Benesch, the art of the menu was largely neglected. Sensing some room for disruption, Baker convinced restaurateurs to invest in fully customized designs.

Benesch, with a variety of menus she’s worked on (Michele Benesch)

Benesch never expected to enter the family business. But she couldn’t fully escape it, either. When she went out to dinner as a kid in Miami, her father, who ran the company at the time, always pointed out little menu tricks. He’d ask her about the materials used (“Why did this client choose a parchment?”), the fonts, the placement of each item.

“My whole life, I was being an apprentice for the job I never realized I wanted,” Benesch says.

By the time Benesch took over the business in 2006, the menu engineering trade had begun to gain wider recognition, with a growing number of hospitality schools funding research into the psychology of menus.

Consultants like Benesch realized they could use this research to get customers to spend more money.

Today, Benesch blends design, psychology research, and general food knowledge to build a more scientific menu. With a bit of tinkering, she can increase the odds of, say, a diner picking the highest-margin meal on the menu.

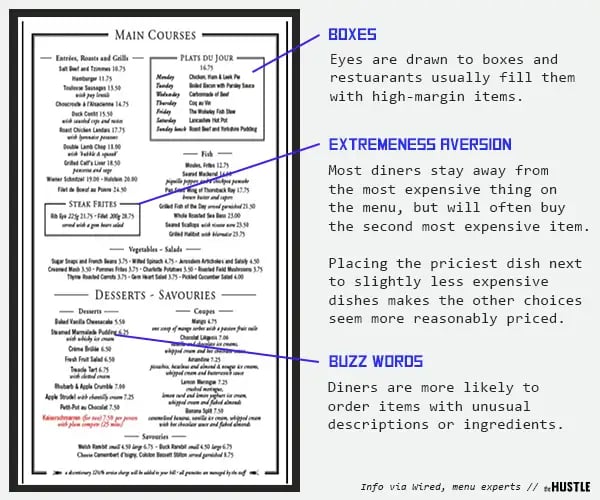

A few simple tricks engineers sometimes employ to optimize menus (The Hustle)

Considering how small restaurant profits are (typically 3% to 5%), the right menu can mean the difference between success and failure.

When a Las Vegas restaurant recently hired Benesch to revamp its menu, she cut their 4-page layout down to a simple 2-page panel, upped the font size, did some dish repositioning, and cut loose some of the dishes that weren’t selling well.

The new menu led to a spending bump equivalent to $9 more per customer.

The subtle power of a restaurant menu

An engineered menu won’t convince you to order something you normally wouldn’t. The point is to reach you at a moment of indecision. Torn between 3 different dishes? A well-designed menu is laid out so that your eyes gravitate toward the priciest dish.

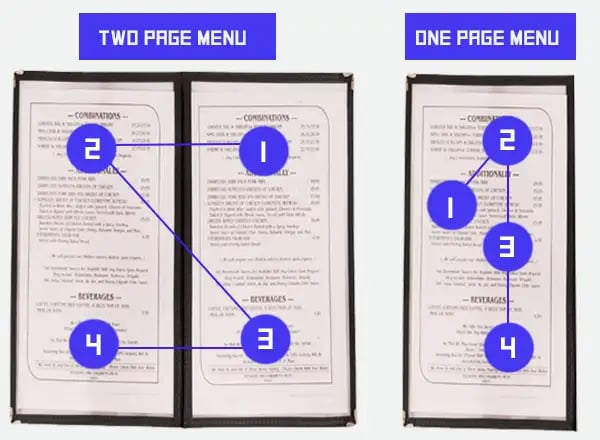

Say you unfold a two-page menu. Your eyes will almost always follow the same reverse “Z” pattern: Top right, top left, bottom right, bottom left.

One-page menus are different; most people’s eyes land about ⅓ of the way down from the top, then move up, then scroll back all the way down.

The Hustle

In the hands of someone like Benesch, this knowledge can be a powerful revenue generation tool.

The prime real estate of a menu — that upper-right corner — is often reserved for high-margin dishes or supplemental items like appetizers.

Benesch will often draw more attention to these items by adding design details, like a box or a touch of bolding. Highlighting certain items, though, is a delicate dance: overdo it, and the whole menu just winds up looking chaotic.

Benesch relies on a few ground rules. When she’s working with a particular section — say, “Sandwiches” or “Appetizers” — with under 8 items, she’ll only add a box around 1 dish. If the category has between 10 and 12 items, she’ll bring that up to 2.

A few of the myriad strategies employed by menu engineers like Benesch:

- Using words like “signature,” “original,” and “famous” to make high-margin items more appealing.

- Removing the dollar sign ($) from the dish prices. Studies show that customers spend more when the price is presented as a standalone number.

- Enlisting the magic number for items per food category. At fast-food joints, it’s 6; for snazzier joints, it’s 7 appetizers/desserts and 10 main courses.

- Retooling design elements: menus with big fonts and no more than 20% white space improve the dining experience.

Another strategy: If you’ve noticed shops selling dishes that feel particularly over-the-top — say, the $1k “Golden Opulence Sundae” from Manhattan’s “Serendipity 3” dessert shop, or Ben & Jerry’s 20-scoop Vermonster — you might have stumbled across a “decoy item.”

As Gregg Rapp, a prominent menu engineer who has worked in the industry for 38 years, explains it, decoy items are not actually designed to be ordered.

The goal, he says, is to “get dopamine kicked into your brain.” You probably can’t afford to buy a golden sundae, but its mere existence excites you about the rest of the menu.

Gregg Rapp has worked on hundreds of restaurant menus all across America (Gregg Rapp)

All of these design strategies generally serve one overarching goal: making a menu as accessible as possible.

Not every restaurant follows these principles.

Take the Cheesecake Factory, whose 21-page menu is the stuff of fast-food legend. Its menu is bulky, confusing, and riddled with a hellscape of fonts and garish-looking ads.

“What that menu does is it overwhelms a person,” Rapp says.

But even this menu mayhem is by design: unless you’re a Cheesecake Factory aficionado, you will usually turn to your servers for help — and servers can point you to higher-price items.

Can you engineer a smartphone menu?

In the before times, when Benesch walked into a new client’s restaurant, she could quickly identify what needed fixing.

But COVID-19 has thrown even the most astute of menu engineers for a loop. Since the spring, she’s been commissioned by dozens of restaurants looking to refashion their menus to be more delivery-friendly.

The strategy of a delivery menu is different from that of a table menu: It must be easy to digest, short, and focused on items that keep well, rather than those that are the highest priced.

“Someone could make a beautiful beef wellington that could melt in your mouth,” Benesch says. “It’s not going to travel 12 city blocks and taste the same.”

COVID-19 has shifted the focus of menu engineers to delivery and takeout menus (Joe Raedle/Getty Images)

For menu engineers, the more dramatic change is the shifting medium.

Restaurants are investing heavily in QR codes. Instead of thinking of a customer unfurling a basic two-page menu, Benesch has to ask herself, “How will this look on a smartphone menu?”

That shift has called the fundamental truisms of menu design — like the trajectory of a diner’s eyeballs — into question.

Benesch has attempted to pivot quickly. She’s one of a handful of engineers already offering QR code menu designs. And when designing a smartphone menu, she has decided to cast aside some longtime no-nos.

She used to avoid using multiple font sizes on the same menu page, but when she’s dealing with a QR code, she’ll just up the size of the item she wants to highlight by 2 point sizes. She’s adding more boxes and color differentials than usual — anything that will grab attention.

“We go back to pictures, we go back to colors, we go back to a more stylish approach,” she says. “We’re in uncharted waters. The psychology of how you open up a menu no longer applies.”