In the summer of 2001, Jim Cantrell received a phone call while he was driving around Logan, Utah.

“Is this Jim Cantrell?” the voice on the other line asked.

“Yes it is, how can I help you?” Cantrell said.

The stranger replied in one breathless answer:

“I’m Elon Musk. I’m an internet billionaire, I founded PayPal and Zip2. I could spend the rest of my life on a beach drinking Mai Tais, but I decided that humanity needs to become a multi-planetary species to survive and I want to do something with my money to show that humanity can do that and I need Russian rockets and that’s why I’m calling you.”

Cantrell misheard the stranger’s name as “Ian” Musk but soon confirmed the South African entrepreneur’s identity.

Over the next year and a half, the 36-year old Cantrell — one of the world’s most formidable experts on space technology — would help the 31-year-old Musk:

- Learn rocket science, including lending him 4 books (which he says Musk has “yet to return”)

- Meet rocket experts and a network of leading space minds

- Travel to Russia 3 times, in an (ultimately failed) attempt to procure 3 ICBMs for a cool $7m each

- Launch SpaceX as one of its first 4 employees

- Catalyze what has become a $366B industry

To understand what led Musk to call Cantrell, The Hustle had an extensive conversation with the space veteran and read an early draft of a forthcoming book that gives his inside account of the new Space Race.

The story that follows tracks Cantrell’s incredible journey through some of America’s most storied space institutions, the fall of the Soviet Empire, and the early days of today’s private space industry.

***

- The journey begins with soapboxes and Carl Sagan

- The NASA poster that changed everything

- Another surreal opportunity: Jet Propulsion Lab

- On a collision course with the Soviets

- An innovative design and a new life in Europe

- The collapse of the Soviet Empire and the end of the Mars Project

- The most eventful years of his life

- SpaceX, the new Space Race and beyond

***

1. The journey begins with soapboxes and Carl Sagan

Born in the mid-1960s, Cantrell began his life on a chicken farm in Yucaipa, California, a town 70 miles east of Los Angeles. While the town was quiet, the farm itself provided ample resources for a curious child.

“I would attempt to build anything,” Cantrell recalls. “I had a treasure trove of things to draw upon: whatever I found lying around the barns and workshops.”

He had a particular fascination with cars, building a go-cart out of a lawnmower and taking part in soapbox derbies. It’s an interest that continues to this day in the form of competitive racing.

The experiences were foundational for Cantrell’s future endeavors. “The go-carts were like a start-up business and they received all of our energy, creativity, and money,” he told me in a 2+ hour conversation this fall.

At 15, Cantrell took an interest in physics and space thanks to the TV show COSMOS, hosted by Carl Sagan. “The way that he described the way the world worked gave me a sense of awe and wonder,” Cantrell says of Sagan, a hero he would one day meet.

***

2. The NASA poster that changed everything

In the late 1970s, Cantrell relocated to San Jose, after his mother remarried. It was during the time when actual silicon (e.g., semiconductors) ruled the valley.

Then, in 1982, the family moved to Utah, and Cantrell enrolled in Utah State University (USU). The school — located in the sleepy town of Logan — would prove instrumental in setting Cantrell’s path.

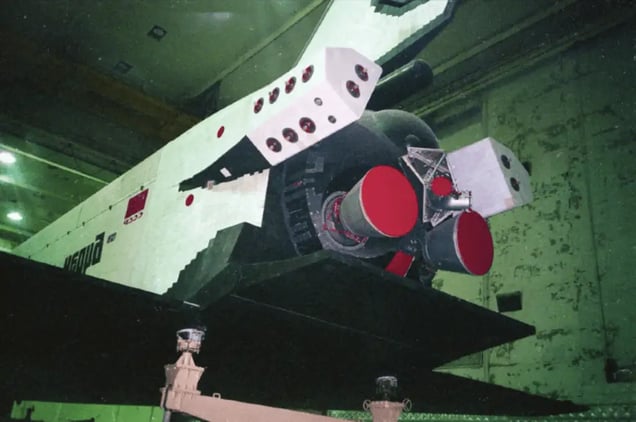

At the time, Utah was no space laggard. It was home to Morton Thiokol, an aerospace company that built the rocket boosters for NASA’s space shuttle (including the ill-fated 1986 Challenger launch) and helped propel over 400 payloads into space since the 1940s.

Cantrell started in electrical engineering but switched to mechanical engineering in his second year. It was a fortuitous change.

In his senior year, Cantrell discovered a new course: Mechanical Engineering 595 (Space Systems Engineering). The course was being funded by NASA with the aim of designing a Mars Rover for the space agency.

After enrolling in the course, Cantrell paid a visit to the head of the NASA design course, Dr. Frank Redd.

“I knocked on [his] half-open door and a voice responded ‘come in,'” Cantrell recalls. “This wasn’t a normal voice, mind you. This was the voice that had a decisiveness to it. This was the voice that commanded you to move forward. This was the voice of a full bird Air Force Colonel.”

***

3. Another surreal opportunity: Jet Propulsion Lab

Dr. Redd accepted Cantrell into the design program. Two teams set off to create competing designs that would later be presented at a NASA conference in Washington, DC.

“To us, NASA engineers and managers were like gods,” Cantrell says. “They built the Apollo space program, Viking landers, and put a man on the moon.”

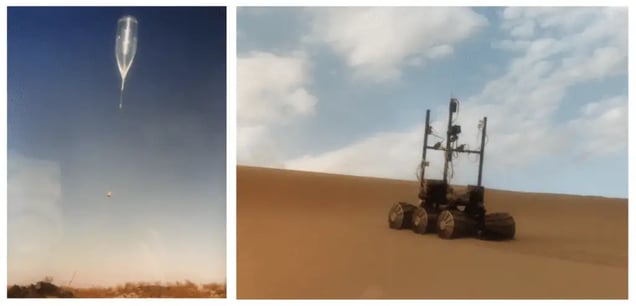

Cantrell worked on a Mars balloon that could carry a payload across the planet’s surface, while the competing team created a wheeled rover design. The DC trip — which may or may not have included Cantrell peeing on the lawn of the Soviet embassy — proved to be a success.

Not long after, the Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in Pasadena, California, had openings for a pair of young researchers. As Cantrell remembers it, there were other more qualified candidates, but Dr. Redd chose him for the gig as the other candidates had personal conflicts with moving.

Cantrell was blown away by the opportunity. “Since the 1950s, the JPL had built the majority of the US deep space probes to Mars, Mercury, Venus, and the other planets,” he says. “It’s hard to overstate the relevance of JPL to the exploration of deep space. I had zero expectation that I would ever be picked to work there and it was one of the highest honors of my life.”

Cantrell’s new boss at the JPL lab was Jim Burke, a “modern Renaissance man” who began his career as a naval aviator and eventually led the Ranger lunar mission in the early 1960s that was America’s response to Russia’s Sputnik launch.

At a time when space missions were put on hold due to the 1986 Challenger shuttle tragedy, working at JPL and near Burke was an opportunity to experience the energy of a previous period. A period when America went to space.

Fortunately, Burke had secured NASA funding to design a Mars balloon… one that was meant to be launched to the Red Planet.

***

4. On a collision course with the Soviets

As fate would have it, JPL wasn’t the only organization that wanted to create a Mars balloon. The French Space Agency — AKA Centre Nationals D’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) — was also working on one.

There was one catch, though: CNES planned on delivering its Mars balloon on a Soviet rocket in 1992.

The French-Soviet space cooperation had begun in 1966 when France’s President Charles de Gaulle visited the Russian steppes of Baikonur (in what’s now Kazakhstan) to watch a rocket launch with Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. He was the first Western leader to do so.

As part of the Soviet Union’s political process of opening up to the international community in the mid-1980s (called glasnost under the leadership of Mikhail Gorbachev), the French proposed that America participate in a joint Mars project.

This was still very much at the height of the Cold War, though. “You have to remember, when I was growing up, the threat of a Soviet nuclear attack was ever-present,” says Cantrell. “From what I grew up learning, I always thought the Soviets were a 12-foot tall super race ready to eradicate us.”

The seeds for Soviet-US cooperation were planted by The Planetary Society (TPS), a space advocacy group that was privately funded by citizens. It was founded by Lou Friedman (a former colleague of Jim Burke’s) and the astrophysicist Carl Sagan.

“Lou wanted to bridge the gap between the Soviet and American people,” Cantrell explains. “The Mars balloon project was a way to demonstrate that we could work together independent of national boundaries.”

***

5. An innovative design and a new life in Europe

Over an 18-month period in 1988 and 1989, Cantrell worked on an innovative Mars vehicle design. To navigate the treacherous terrain of the Red Planet, he created the Mars Snake, a 30-foot titanium exoskeleton.

Based on his insights and tireless work, CNES invited Cantrell to Toulouse to become a project manager for the foreign space agency. While there, Cantrell worked with both French and Soviet space experts on the Mars mission.

The period was very important, Cantrell told us: “It was the birth of citizen-led space efforts pioneered by The Planetary Society, the beginning of US-Russian space cooperation that would lead to the International Space Station (ISS), and the seeds that led to SpaceX.”

The Mars project continued to progress, with Cantrell heading to Latvia in early 1991 to prepare the snake. In addition to the surreal experience of visiting the Soviet Union for the first time, the entire experience was partially complicated by America’s invasion of Iraq.

While the Iraq conflict didn’t directly affect Cantrell’s work, another major geopolitical event would completely derail the joint Mars project.

***

6. The collapse of the Soviet Empire and the end of the Mars Project

“I was in Riga (Latvia) on August 20th, 1991,” Cantrell remembers. “Soviet radio typically plays political shows with lots of chatter — but when I woke up, the national anthem was on repeat. I knew something was going on.”

As it turns out, a group of Communist hardliners had tried to pull a coup and overthrow Mikhail Gorbachev, the country’s moderate president and Soviet Communist Party leader. Led by future Russian president Boris Yeltsin, the resistance movement pushed back.

Yeltsin famously stood on a tank in front of the Duma in Moscow and gave an impassioned speech. The resistance was successful and the episode heralded the beginning of the end of the Soviet empire, in a mostly peaceful manner.

Cantrell traveled to Moscow and saw “stunning displays of flowers in tank barrels” and — more amazingly — “an abundance of Russian flags” which foreshadowed the nationalist movements that would arise from the ashes of the Soviet empire.

“With the dissolution of the Soviet empire,” Cantrell says, “we knew the Mars project was over. There was no more money.”

By the start of 1992, Cantrell was on his way back to the United States, jobless.

***

7. The most eventful years of his life

With no more Soviet threat, defense spending dried up and the aerospace industry saw jobs vanish overnight.

This was the employment market that Cantrell returned home to. His job search was made even tougher by the fact that he had worked so closely with the Soviets.

“I applied for a job at Martin Marietta, which would later become Lockheed Martin,” says Cantrell. “I was particularly interested in the company because of one of its executives, Bob Zubrin. Bob is the author of The Case for Mars and, at the time, was proposing a program called Mars Direct, that would send a vehicle to the planet in preparation for a manned mission.”

Cantrell visited Zubrin in Denver and was treated like a “Soviet spy.” While he didn’t get the job, the connection he made would prove invaluable. After striking out with Martin Marietta, Cantrell called his old mentor Dr. Redd, who immediately hired him to work at USU’s space lab.

While at the lab, Dr. Redd introduced Cantrell to his old colleagues from the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA). Cantrell initially thought he was being detained for his Soviet connections, but there was a larger mission afoot.

With the end of the Soviet empire, US officials were concerned that extremely bright (but very poor) ex-Soviet nuclear scientists would sell their knowledge to the North Koreans or Iranians.

Cantrell was being recruited for his old connections with a mission to travel to Russia — which had turned into the Wild West — and help stop the scientific brain drain.

Through the mid-1990s, he would go back and forth from Moscow, traveling to bazaars where you could buy nuclear launch systems, intercontinental ballistic missiles, and other weaponry — right next to Russian stacking dolls.

“My previous experience served me well during this mission,” he recalls. “The 5-year period that I did this was perhaps the most eventful and entertaining of my life.”

***

8. SpaceX, the new Space Race, and beyond

Fast forward to the summer of 2001.

“When Elon first contacted me, his plan was to send mice to Mars and back to prove that living creatures could survive the round trip,” Cantrell tells me. “His hope was that a successful trip would inspire humans to do the same and become a multi-planetary species.”

To complete the mission, Musk decided that he would need cheap Russian rockets, and Bob Zubrin — the former Martin Marrieta executive and Mars-phile — said Cantrell was the man who could deliver the goods.

So began Cantrell’s 18-month adventure with Musk. While the Russian rockets were never procured, Cantrell introduced Musk to many of the space sector’s key players and helped to build out the early SpaceX team.

In the nearly two decades since Cantrell left SpaceX, the company has completely reshaped the space industry, which today is worth $366B a year.

What was once a mission-critical part of the US government’s budget has transformed into the private pursuit of the world’s richest (and most ambitious) entrepreneurs.

After a number of successful rocket launches (and returns), SpaceX became the first private entity to send humans to space in June 2020.

Today, Cantrell — the father of 6 children — lives in Arizona. He remains in the space industry with his launch startup Phantom Space. When asked about the SpaceX days, he readily admits he underestimated Musk.

“I didn’t believe in his commercial space strategy and plan to colonize Mars,” Cantrell says, which were among the reasons he left SpaceX. “Elon has proven me wrong. He’s very smart — but what sets Elon apart is his determination. He has dogged determination and has never given up. I’m grateful to have been a part of SpaceX’s early days and cheer on their success.”

If Cantrell would change one thing, it would be this: “I wish Dr. Redd could have seen it all happen.”

***

Author’s Note: The piece came together after this tweet went viral and I later connected with Jim. Just highlighting to note that I love Twitter haha