Kelvin Fichter never really wanted the four-thousand-pound IBM server that now occupies most of his studio apartment.

The software engineer had taken up the hobby of trawling government auction sites — mostly just to admire the strange assortment of items that wind up there. But when he spotted the server on GovDeals in June of 2019, he felt the need to place a bid.

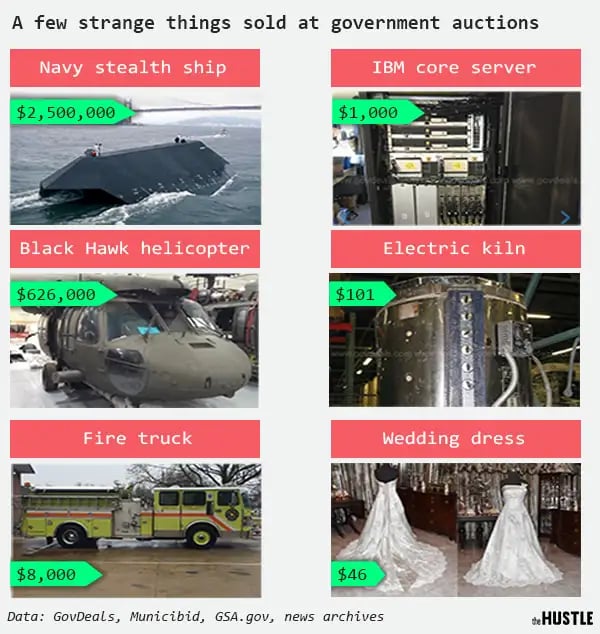

GovDeals is one of at least a dozen auction sites that sell surplus government property to the public. Among the listings, one might find player pianos, school projectors, laptops. Black Hawk helicopters, McLaren sports cars, wedding gowns, jewelry, animals, and even a top-secret Navy stealth boat.

The Coast Guard once auctioned off a lighthouse in Wisconsin (purchased by a San Francisco tech executive for $159k). Maryland police officials put up a straw hat signed by the likes of Charlie Chaplin and Ronald Reagan.

Once an item falls out of use, organizations running the gamut from state colleges to law enforcement to the Environmental Protection Agency auction it off to the public.

And sometimes, an extraordinary item ends up in the hands of someone like Fitcher.

Server, meet forklift

Last May, while he was conducting his usual search of GovDeals, Fichter saw a server he recognized: The IBM p5 p590.

No one had bid on it, and the offering was dirt cheap considering that, when the server first appeared on the market in the early 2000s, its list price approached $1m.

Fichter with his new server (via Kelvin Fichter)

The seller was the University of Connecticut’s cash-only Public Surplus Store, a small warehouse of musical instruments, television sets, and computer hardware that the school no longer needed. On a whim, Fichter submitted a bid of $1k.

“I put the bid in as somewhat of a joke, to be completely honest,” Fichter said. “Then, of course, I get this email that said you won this auction and you have 10 days to come pick this thing up.”

Public agencies have a simple rationale for wanting to get rid of mountains of their leftover stuff: Revenue. All of the money generated is returned to the agency that sold it. The University of Connecticut, for instance, funnels those sweet, sweet IBM server profits back into the university’s $1.5B general budget.

But where agencies see a way to earn some extra cash, consumers are finding a netherland of impossibly cheap government items. The only trouble? They have to put up with a few quirks.

One such quirk: Almost all public auction sites expect buyers to pick up their orders in person. For Fichter, a New York City native, that posed several problems.

For starters, he didn’t have a driver’s license. Then there was the fact that there was no conceivable way he’d be able to fit a 4k-pound server — an item nearly the size and weight of a full-grown rhinoceros — into a car.

Strange things often end up on government auction sites (The Hustle)

But Fichter didn’t have a choice.

“It was either purchase the server from GovDeals,” he said, “or I’d be banned from GovDeals forever.”

He went with the server. With the help of a friend, Fichter rented a U-Haul truck and drove to the University of Connecticut. There, the duo found a server so massive that the UConn employees wheeled out a forklift.

Wait… why does this exist?

The American public auctions system contains a tangle of platforms, sales strategies, and logistical hurdles.

Some localities, like Clark County, Nevada. and the city of New York, host semi-regular open auctions that function like yard sales. Others, like Milford, Connecticut, rely on a much older system: The city puts a classified ad in the local paper, and citizens have to come to the mayor’s office and fill out paperwork in person in order to submit a bid.

But most public auctions today happen online, through an equally scattered assortment of websites.

There’s GovSales.gov, the major publicly run website operated by the General Services Administration; Property Room, which specializes in confiscated items kept in police custody; and a string of other private companies, like GovDeals, Public Surplus, and US Gov Bid, that work with local agencies to sell surplus property.

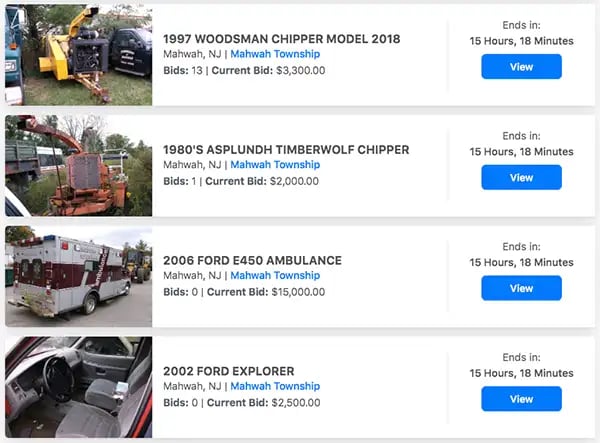

Among those private contractors is Municibid, a Philadelphia-based company that has contracts with organizations like the Philadelphia International Airport and the state of New Jersey.

Greg Berry founded the company in 2006. Back then, government-auctioned items consistently sold for less than they did on competitors like eBay, largely because no one really knew that government auctions existed.

Items listed for sale on Municibid include wood chippers and ambulances (via Municibid)

What Municibid offers is marketing. Government employees don’t really have the time to curate a sophisticated PR strategy for the haphazard array of items they auction, but private contractors do.

According to Berry, Municibid has landed its public contracts by promising to bring up the final bidding price of its auctions.

He points to the town of Bart, Pennsylvania, which expected to make $3.2k auctioning off an old Ford F-450 One Ton Dump last year. Instead, with Municibid, they brought in $12.1k. That’s good for local governments, which get to keep all of the proceeds, and good for Municibid, which charges buyers a service fee.

The 10-person company runs ads on social media, maintains active email lists that reach around half a million subscribers, and reaches out to trade magazines to attract bidders for some of its more niche items (see: advertising a coach bus on the website BusesOnline.com, or a “tub grinder,” which is used to clear land, on ConstructionEquipmentGuide.com).

About that fire truck in the backyard

The deals on government auction sites are so good that some business-minded publications urge startups and small business owners to buy equipment from GovSales in order to save money.

But while some businesses may peruse public auction sites to cut costs ($5 sofa, anyone?) the primary public property buyers are strangely… ordinary.

When Berry first launched Municibid, a lot of the buyers were professionals. But the increasing ease of online shopping has since shifted his consumer base. “Now what we find is that the general public is buying things for DIY projects, general use things, parents buying their kid’s first car,” he said.

A 1984 Pierce Dash fire engine up for the taking in Guntersville, Alabama (via Facebook)

In his nearly 15 years on the job, Berry has sold lawnmowers, tractors, snowplows, dump trucks, cafeteria equipment, parcels of land, and ambulances and police cars with their lights and sirens stripped off. Sometimes farmers will even buy old fire trucks and use them to store water on their farms.

After a state hospital closed, Municibid helped to sell a leftover morgue table. Despite his great curiosity, Berry never did figure out why that customer wanted a morgue table.

“I’m never surprised as to what is listed or what is sold or potentially what things are used for at this point,” he said.

The no-shipping dilemma

That doesn’t mean the auctions always go smoothly. Things can backfire, and there can be surprises for both sides.

One of the most famous government auction stories involves a set of three Apollo 11 moon landing tapes that a NASA intern unknowingly bought at a government surplus auction in 1976.

The 2.5 hours of original footage were kept in a box of 65 other videotapes, purchased by the intern, Gary George, for just $217.77. Last year, after realizing what he’d found, he sold the three tapes for $1.82 million.

Despite their extensive catalog, government agencies are unlikely to ever become a real competitor to Amazon or eBay. That’s in part because of the annoying restrictions — namely, that pesky no-shipping rule. The General Services Administration specifies that customers must either pick up the items themselves or hire a third party to coordinate the transport.

TOP: Original footage from the Apollo 11 voyage, purchased by a NASA intern at a government auction in 1976 for $217.77, sells for $1.82m at Sotheby’s in 2019 (via Sotheby’s); BOTTOM: Buzz Aldrin stands on the moon during the Apollo 11 landing in 1969 (via NASA)

The other problem is that, when buying from the government, you don’t always know what you’re going to get.

Emily Cardinali, a freelance producer and writer, recently moved to Florida to care for her sick father. The shift was stressful on many levels and last year, she decided she needed a creative outlet. She’d taken ceramics classes in college, so she settled on making pottery.

On the advice of an old classmate, Cardinali turned to government auction sites. She made two purchases: The first was a pottery wheel, which she nabbed from a public community center a few towns over. Her second purchase was a kiln from a Florida high school.

There were no photos posted online, but the deal seemed too good to ignore. After a small bidding war, Cardinali bought the kiln for around $150 — about 10x less than the usual price.

Cardinali borrowed her dad’s truck to pick it up. But when she arrived, she said, “the kiln was in all kinds of disarray.” Some of the bricks were broken in half. While Cardinali still uses her pottery wheel every day, she decided to dump the kiln.

Surprisingly, the private company that sold the kiln did eventually decide to refund Cardinali. They didn’t have to. In the public auctions world, money-back guarantees are virtually nonexistent.

The afterlife of an IBM server

For Fichter, the biggest challenge came not in buying the IBM server or lugging it into his studio apartment, but in deciding what to do with it next.

He didn’t really need the server to run. He was just fascinated with the mechanics of early 2000s electronics. Merely turning it on requires a much stronger power supply than his apartment building offers.

He soon started disassembling the server and cataloging every piece. “I wanted to understand what every component did,” he said.

The dissected server in Fichter’s NYC studio apartment (via Kelvin Fichter)

But here’s the thing about some of the more obscure auction items: They aren’t really practical. Understandably, the spatial impracticalities of storing a two-ton server in a New York City studio apartment have begun to take a toll.

So Fichter has decided to repurpose his server. He wants to layer it with wood and glass paneling and turn it into furniture.

After paying $1k, renting a U-Haul, and enlisting a forklift at the University of Connecticut, Fichter has a firm vision for his gigantic IBM server. You could say he is following in the footsteps of the farmers who store water in their government-issue fire trucks: He’s finding a radically new purpose for out-of-date government equipment.

“The end goal,” he said, “is to make it into somewhat of an art piece.”