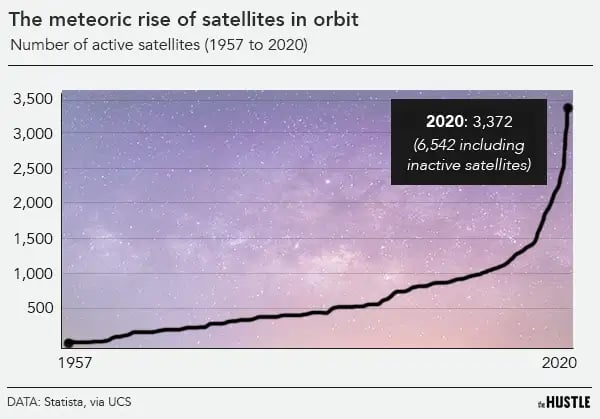

If you have any doubt about the meteoric growth of the satellite industry, consider this:

- In 2019, there were ~2k high-tech devices orbiting the planet

- Today, there are more than 6k

- By 2030, there will be an estimated 50k

For decades, these extraterrestrial bodies were the preserve of governments and multi-billion-dollar firms like Boeing, Lockheed Martin and AT&T. Then, 3 things changed:

- Rocket launches got cheaper

- Satellites got smaller

- Data analysis software became more advanced

These shifts shepherded in a host of private players and led to an explosion of readily available, high-resolution satellite imagery.

The Hustle

Satellites have tons of familiar applications, from predicting the weather to tracking delivery drivers and beaming live sports to our televisions.

Now, so-called NewSpace innovators are broadening the industry, using images of Earth to develop creative applications that solve a broad range of problems.

Orbiting eyes in the sky have been used to uncover China’s Uyghur internment camps, predict the price of copper and help indigenous communities fight deforestation. They could change the way we buy coffee or rent an apartment.

But the meteoric rise of satellites is raising red flags about surveillance and space pollution — and critics are wondering if the arm of the law can reach beyond the atmosphere to solve the problems raised by fast-evolving tech.

How did space become profitable?

In 2011, NASA’s Space Shuttle was retired from service, marking the end of the 30-year program.

The reusable spacecraft was supposed to make space travel routine and accessible. But slow turnaround, tragic casualties and high costs impeded that goal.

The dream was not forgotten.

In July — after 17 years and over $1B in expended capital — Richard Branson made his first suborbital flight aboard Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShip Two, beating Jeff Bezos to space by 11 days.

The flight was more of an advertisement than an end goal: 600 tickets have been purchased for future flights at $250k a pop.

If promises are fulfilled, those seats will more than 2x the number of people who have been to space and transform space tourism into a consumer business much like Virgin Atlantic Airways.

Top: Virgin Galactic’s VSS Unity spaceship in flight; Bottom: Richard Branson chugs victory champagne post-flight (Photos: Virgin Galactic, Patrick T. Fallon/AFP via Getty Images)

Branson and his cohort of super-rich stargazers are heralding a new space race in which companies compete not just with one-off feats of technological superiority but to develop profitable business models.

Their endeavors are bringing about technological advances that lower the barrier to entry into the space economy.

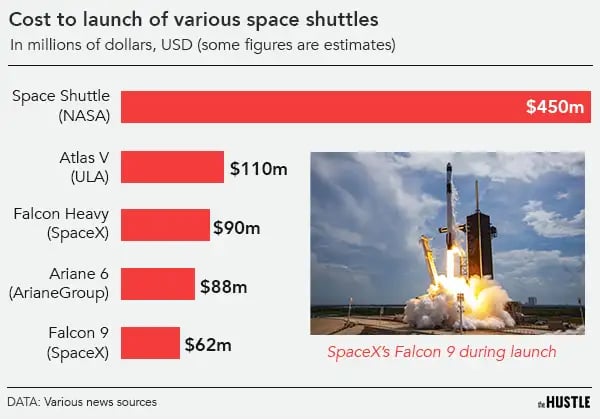

It’s hard to tell that story without mentioning SpaceX, which revolutionized the rocket launch industry by dramatically lowering the cost of launch.

In 2015, SpaceX launched 11 communication satellites with the Falcon 9, the first reusable rocket capable of delivering an object into orbit.

Since then, reusables have lowered the average industry-wide cost of launch from $200m to $60m, making it cheaper than ever to launch an object into space. To put that in perspective, NASA’s Space Shuttle cost about $450m per launch.

The Hustle

An affordable launch makes it viable to develop profitable businesses in fields like space tourism, zero-g medical research, and space station cargo delivery.

Floating millionaires make for good headlines but something a little less sexy is a much bigger business: satellites.

The satellite industry brings in 73% of all revenue generated by the global space economy and it’s already making big changes to life on Earth.

Satellites you can hold in one hand

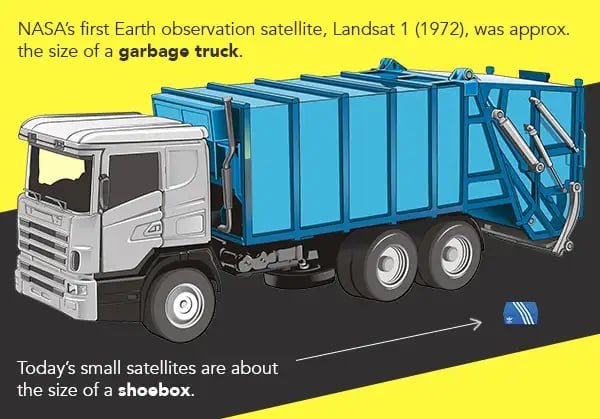

Around the early 2000s, satellites began to see rapid changes that dramatically reduced their size:

- The first Earth observation satellite, Landsat 1, which was launched by NASA in 1972, weighed 1800kg and was roughly the size of a garbage truck.

- Today’s so-called ‘smallsats’ weigh as little as 12kg and are about the size of a shoebox.

The Hustle

Readily available, miniaturized electronics like those found in a smartphone made this shrinkage possible while standardized units called CubeSats allow for mass production of off-the-shelf components.

Affordable launch solutions, tailored specifically to the low-fuel requirements of lightweight smallsats, made it possible for smaller companies to enter the NewSpace race.

A number of companies have made moves in the smallsat space:

- SpaceX’s rocket ‘rideshare’ service allows companies to hitch a lift for smallsats from just $1m.

- Rocket Lab is leading a new trend towards small rockets designed specifically to launch smallsats. Their Electron rocket carries only 300kg at a launch cost of $7m.

- Open Cosmos offers a get-into-space service that allows companies to outsource the design, manufacture, launch and operation of a satellite for as little as $800k with a turnaround of under a year.

Open Cosmos’s VP of Operations, Aleix Megias Homar, says he’s seen increased interest from startups, researchers and smaller countries.

“Space has become a tool rather than an end,” he explains. “Our clients want to obtain unique data and build solutions to some of the world’s biggest problems.”

Turning pictures into numbers

As satellite hardware has shrunk, software has also become more advanced.

Machine learning made it possible to quickly identify and count objects, and detect change over time.

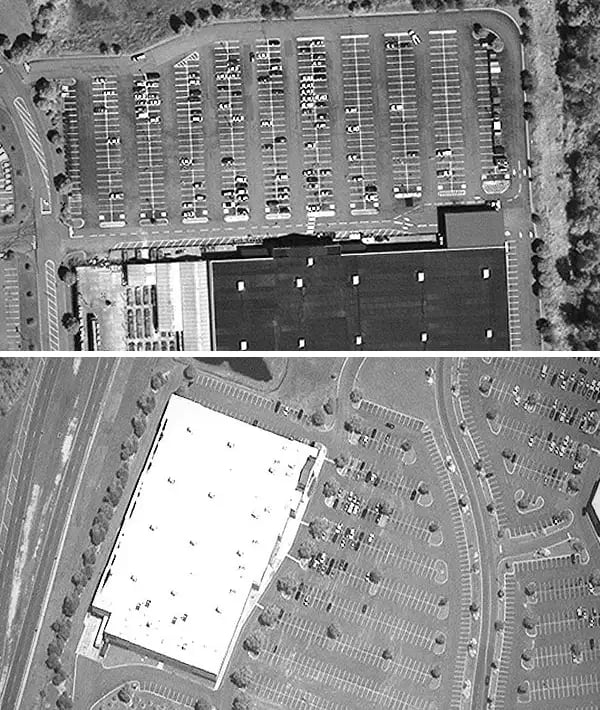

Companies like RS Metrics are now using satellite data to sell services to the commercial market. They collect, for instance, data on the number of cars parked in more than 65k retail parking lots (Walmart, Home Depot, McDonald’s).

Satellite imagery of parking lots helps investors spot economic trends (Via The American Enterprise Institute)

This data can be used to monitor economic growth, establish the value of a property, or help retailers manage supply chains.

RE Metrics’s other products include:

- MetalSignals, which monitors activity at metal processing and storage facilities to predict metal prices and related trends

- EV Tracker, which provides investment data based on activity at electric vehicle factories

The company’s CEO, Maneesh Sagar, says he foresees a future where satellite imagery is an integral part of every industry. “In 2021,” he says, “it’s at the point where small to medium businesses can afford to start using this data to make everyday decisions.”

Custom satellite images can be obtained for less than $2/km² for medium resolution and $15/km² for very high resolution.

Capturing every part of Earth, multiple times a day

Business intelligence isn’t the only application of this accessible data.

In 2020, RS Metrics worked with researchers from Harvard University to date the first surge of coronavirus by analyzing car numbers at hospital parking lots in Wuhan — a technique that could be used to identify future disease outbreaks.

And since the early days of Earth observation satellites, they’ve been used to monitor another pressing global concern: the environment.

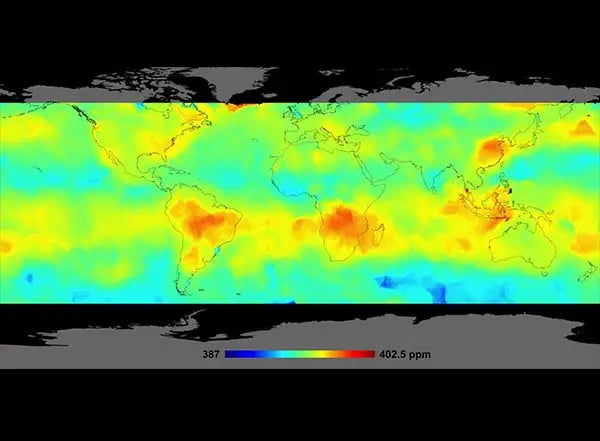

Satellites track CO2 emissions (Via NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Satellite company Planet is a trailblazer in the field of Earth observation.

The team has 150 active satellites capturing 1.2m high-res images per day. And the level of detail has skyrocketed: In 1979, NASA’s Landsat 1 satellite could capture a single pixel image of a football field; today, Planet can do the same with a football.

The company’s portfolio of services includes:

- Mapping C02 super-emitters

- Assessing disasters like floods and oil leaks

- Identifying potential wildfire hazards in California’s forests

- Tracking the bleaching of coral reefs

This kind of imagery is particularly useful when it informs action.

Deforestation dropped 52% when researchers equipped indigenous communities in the Amazon with data from a Peruvian government satellite. It worked like so:

- Members of each participating village were trained and provided with smartphones.

- When a new site of deforestation was identified by satellite, USB drives containing GPS coordinates and photographs were couriered to the villages.

- A custom app led participants to the site, where they could decide whether to drive off the perpetrators themselves or contact police.

Amazon deforestation patterns observed by satellite (via NASA Earth Observatory)

Saving the planet is also becoming an increasingly commercial pursuit, according to Robin Sampson, founder of Trade in Space.

“We’ve gone from a place where we had environmental sustainability as a kind of aspirational soft target to where it’s a hard legal requirement,” he says. “You can’t sell your goods in Europe unless you can prove how much carbon is contained within them.”

Trade in Space is an Edinburgh-based start-up which is using satellite images to solve problems in the coffee farming sector:

The company sources images of farms and uses machine learning algorithms to immediately detect the area of the farm and the number of bags of coffee in each field. This data can help coffee traders evaluate farms, make trades and manage supply.

Trade in Space has another tool in its belt: Blockchain technology is used to add those bags of coffee to a digital ledger, allowing players at any point in the supply chain to trace the coffee back to the field.

This technology could have major implications for the environment.

In the future, it could allow consumers at the point of sale to access the carbon footprint of a cup of coffee or the volume of water used to produce a pair of jeans.

Enough satellites to light up the night sky

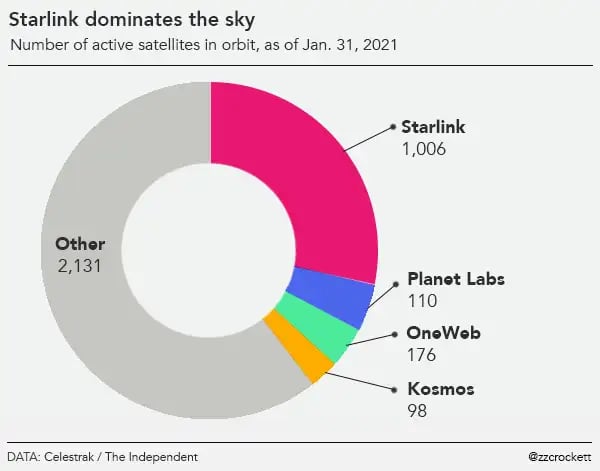

Earth observation may be generating a plethora of exciting opportunities but it’s not the fuel behind the satellite boom: Communication services dominate the skies, accounting for ~61% of active commercial satellites.

One sector, in particular, is set to rocket: an estimated 50% of space economy growth will be in satellite internet services.

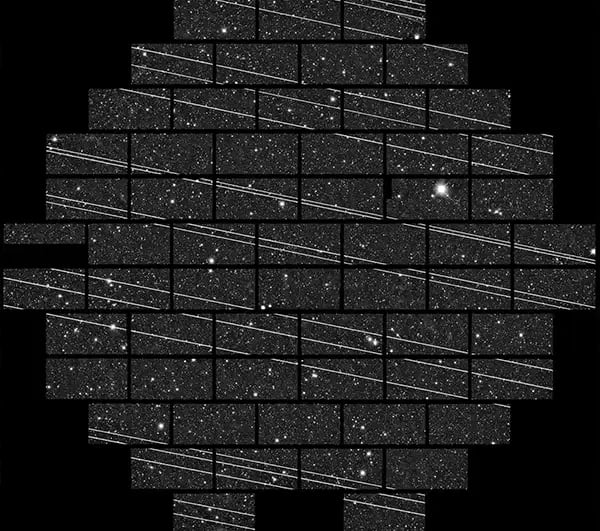

Starlink satellites light the sky (via NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory/NSF/AURA/CTIO/DELVE)

Communications satellites have tons of uses, from air traffic control to banking transactions — but satellite internet has always been too slow and laggy to be adopted anywhere but the most remote places.

That is until SpaceX decided to tackle the problem.

Of the 1,029 smallsats launched in 2020, 773 (75%) are part of Starlink, SpaceX’s global high-speed broadband service. It’s a new approach to satellite internet that relies on a network of interconnected satellites orbiting at low altitudes, meaning data has less distance to travel.

The fleet will eventually be made up of 40k satellites — a number so high that it sparked a legal challenge over concerns it will sully the night sky and impede the work of astronomers.

Starlink is already available as a beta service. Users report competitive speeds and delays of under 30 milliseconds — good enough for online gaming and Netflix binges (although service is currently spotty).

The Hustle

Demand for high-speed internet is bound to grow:

- The coronavirus pandemic has hastened the digitization of shops, workplaces and social lives.

- The Internet of Things, a term used to describe all objects with an internet connection, will expand as autonomous vehicles, connected homes and personal robots become more available.

Satellites could provide the internet to more than a third of people globally who still have no access to the internet, including 14% of people in the US.

So we’ve made it to the future. What could go wrong?

Not everyone feels positive about the satellite boom. There’s something creepy about thousands of unseen cameras staring down at us.

But Owen Hawkins, a director at geospatial intelligence firm Earth-i, argues that, at least for individuals, the current privacy threat from satellites is nowhere near that of cell phones and social media.

He notes that governments already make use of drones and airplanes to capture far more detailed aerial data. (Local government in Slough, England, for example, used a spy plane to identify 6k illegally converted sheds and garages.)

Currently, even the best commercial satellites do not have the resolution to identify a human face or a number plate. Even if that technology were commercially available, federal resolution caps in the US prohibit the use of satellite imagery in which features smaller than 30cm are clearly visible.

Privacy aside, space debris also presents regulatory challenges.

A chunk of China’s Long March 5B rocket ended up in the Indian Ocean (via VCG/Getty Images)

The flotsam and jetsam of increased space activity could collide in Earth’s orbit, damaging satellites and potentially sparking a dangerous chain reaction. In May, an out-of-control 20-ton chunk of a Chinese rocket crashed into the ocean in the Maldives, acting as a stark warning.

There are guidelines for debris mitigation but, according to the European Space Agency, only 15-25% of satellites attempt to comply.

As the problem worsens, the cost of a satellite mission could increase by 10% to cover more protective designs, monitoring, and avoidance maneuvers. It’s hoped the threat of increasing costs combined with improved legislation could lead to a sustainable solution.

Or perhaps a billionaire with a penchant for space will think of a nifty, low-cost solution.