On the set of Mission: Impossible — Ghost Protocol, somebody made the mistake of telling Tom Cruise he couldn’t jump off the Burj Khalifa, a stunt Cruise had been dreaming about for 15 years.

So the actor made the obvious choice. He fired the insurance company and found another one willing to assume the risk.

Once new insurance was secured, Cruise, who has long been famous for trying ever more dangerous stunts as the franchise evolves, set about rehearsing the scene, in which agent Ethan Hunt hangs, runs, and jumps over the side of the world’s tallest building. He nailed it on the second try.

“We all kind of looked at each other and were like, ‘Well, that’s why he’s Tom Cruise.’ We shot it the next day,” said Skydance Production CEO David Ellison after the film came out. “It was spectacular.”

From Marvel movies to the Mission: Impossible series, audiences love watching stunts. But it’s a Hollywood reality that they require insurance, which limits the risks actors and directors take on set and forces studios to weigh costs and safety against producing the most epic blockbusters possible.

It’s a balancing act as tricky as the stunts themselves. So how does Cruise pull it off?

Bespoke policies

In 1919, the silent-film star Harold Lloyd lit the fuse of a fake bomb with a cigarette during a photoshoot. It started to smoke — so much that Lloyd figured the photographer couldn’t see him. He put it aside. Then it blew up.

Lloyd had accidentally been given a functional bomb. The explosion nearly blinded him, and he permanently lost a thumb and forefinger.

The rising star eventually returned to film sets, thanks in part to a prosthesis. But his next films were delayed, and doctors doubted he would ever again perform his signature physical comedy.

Silent-film star Harold Lloyd shortly after his on-set accident (image via Film Star Facts)

Since then, making a Hollywood film or TV show has required insuring the cast.

Show biz is an industry of high-wire, risky endeavors. Even a large, venerable studio like Paramount produces only a dozen or so movies each year, each with a huge budget (of $30m to $300m) and tight schedule that could be blown to hell by Cruise breaking an ankle. (Which happened when Paramount filmed 2018’s Mission: Impossible — Fallout.)

A key actor missing shoots isn’t the only thing an insurer such as Allianz or Chubb will cover.

“You don’t know what’s going to happen next,” says Alex Clegg, lead film underwriter at Beazley, an international insurance company. Risks vary enormously between films, and bespoke insurance policies can include…

- Damage to expensive cars: Anything from a professional stunt driver speeding around in The Fast and the Furious to vintage cars parked in a Depression-era scene.

- Weather interruptions: Whenever productions film “on location,” they risk scheduling chaos from a hurricane blowing through or clouds covering what’s meant to be a sunny scene.

- Stunts: Even when stars stay on the sidelines, underwriters are most concerned about stunts, which can lead to tragic outcomes like stunt performer Joi Harris’ death filming a motorcycle scene in Deadpool 2.

- Film and faulty cameras: Have you ever accidentally deleted a memo you wrote? Now imagine having to re-shoot an entire day of a Marvel movie because you damaged the film.

- Wild animals’ schedules: If a nature documentary needs footage of a rare animal being born or two animals fighting, production could drag on until nature makes it happen.

Alex Clegg (via Beazley)

When a studio or filmmaker comes to Clegg for insurance, they bring along pages of risk assessments. Some exposure is obvious: plans to use safety cables and stunt doubles for an action film. Some is camouflaged: a drama that takes place during WWII will have a scene with tanks and Spitfires. Some is totally unexpected: How will the nature documentary keep antivenom on ice?

The more risks filmmakers want to take — shooting in remote locations over indoor sets, putting Fast and the Furious actors in speeding cars — the higher the premium insurers like Clegg will quote them.

Michael Furtschegger, global head of entertainment at insurance giant Allianz Commercial, says insurance for big Hollywood productions usually costs 0.9%-1.5% of the budget — think $2m for a $200m Marvel movie.

Independent filmmakers raise money from banks and firms. They won’t invest unless the filmmaker also has a completion bond, which acts as insurance for the investors. The completion bond for Terminator 3 cost a reported $2.54m. It’s not cheap, but neither is the worst-case scenario. If Schwarzenegger had gotten seriously hurt or abandoned the movie, the firm providing the completion bond would have paid the investors back their $181.6m.

And when firms provide the funding and insurance, it buys them influence over the movies and TV shows themselves.

The risk engineers

Cruise has been unusually involved in the making of Mission: Impossible. In the ’90s, he championed its transformation from a TV series into a film franchise, and his own production company made the first films for Paramount.

His role as a successful producer has helped him insist, famously, on doing all his own stunts. In interviews, Cruise has described how he grew up doing flips off his house into snowbanks, how he fell in love with cars and motorcycles and climbing, and how he sees performing stunts as part of great acting and filmmaking.

“I feel that you’re bringing everything… physically and emotionally, to a character,” he told TV host Graham Norton. “I’ve trained for 30 years… and it allows us to put cameras where you are normally not able to.”

The Hustle

But any actor who wants to do their own stunts faces a major obstacle: the underwriters and financiers. They influence decisions from the planning stage right on through filming:

- Casting: Actors with a history of injuries or drug problems can become uninsurable. Due to his addiction issues, Robert Downey Jr. became Iron Man only after the director lobbied wary studio executives — and after Downey Jr. agreed to a relatively measly salary of $500k to offset the risk of casting him.

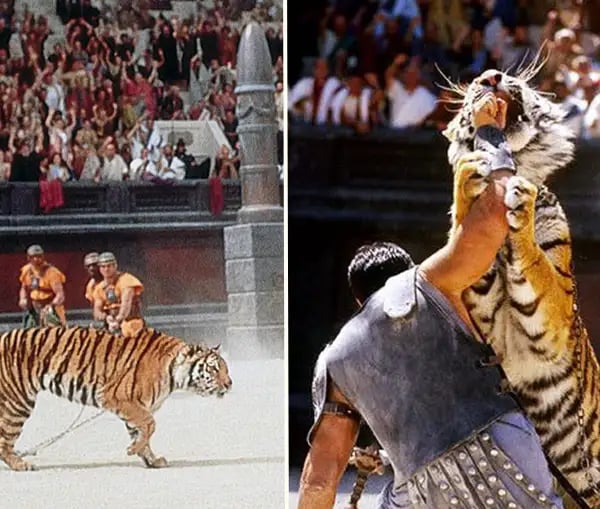

- After-hours conduct: Russell Crowe has joked about how he wrestled with tigers while filming Gladiator, but wasn’t allowed to play friendly games of soccer off-set.

- Budget and schedule oversight: In Tropic Thunder, Cruise plays a producer who calls into the set of an action movie and tells a crew member to punch the flailing director. His character was reportedly based on one of the movie’s actual producers, and the financiers generally receive similar daily updates.

- Risk engineers: Tomb Raider’s marketing touted Angelina Jolie performing risky stunts; but, per Hollywood economist Edward Jay Epstein, the on-set insurance employees (sometimes called risk engineers) actually insisted she be “hand-held by safety men in green spandex suits” or use stunt doubles.

- Takeovers: If a film goes far over budget, insurers can veto expensive special effects, shorten the script, or even replace the director with someone more efficient.

Insurers don’t shut down every risk. Crowe still filmed a fight scene with live tigers, which got closer to the star than anyone intended. Furtschegger describes Allianz’s risk engineers — who often have backgrounds as firefighters or as stunt performers — as collaborators who can suggest ways to film stunts safely.

Russell Crowe wrestled with a tiger in the 2000 film Gladiator (Dreamworks LLC and Universal Pictures)

Still, taking risks regularly involves considerable persuasion.

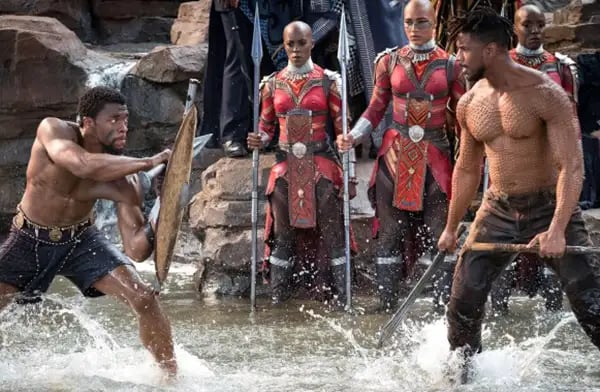

“I have to be a salesman,” says Clayton Barber, who has performed and overseen stunts in films ranging from Black Panther to Zoolander.

When Barber was the stunt coordinator for Creed, director Ryan Coogler wanted to film an entire two-round boxing match in just one take. Barber was skeptical, but went to a gym to try it out. He found it could work.

“But I said, ‘Now, is the studio gonna let us do that?’ Because it’s a liability, you know.”

Barber knew the producers would worry that…

- If they failed to film the fight in one shot, they’d have to redo the pivotal scene, leading to extra costs and schedule delays

- Shooting the fight in one scene meant they couldn’t use a stunt double, risking an injury to lead actor Michael B. Jordan

So he pitched them on the upside: a special scene would generate buzz among critics and fans.

“I said, ‘I’m not doubling, because you can’t double somebody in a boxing movie and make it look good,’” he says. “I said, ‘Did you double Stallone?’ They said no. So I said, ‘We’re not doubling Michael.’”

Michael B. Jordan and Chadwick Boseman in Black Panther (Walt Disney Studios)

Barber and Coogler got the go-ahead, and the fight scene, a violent ballet which they filmed without a cut, generated the buzz Barber had promised.

That kind of buzz is quintessential Cruise: The Mission: Impossible franchise is powered by audiences going nuts for behind-the-scenes footage of scenes like Cruise driving a motorcycle off a cliff.

‘I do my own stunts’

Hollywood specializes in sleight of hand, but Cruise’s stunts are the real deal. He’s an anomaly: a star who really, truly performs his own stunts.

“He is definitely unusual,” says Clegg. “Watching the YouTube videos of the latest stunts is incredible.”

Clegg is referencing how Cruise seems to defy aging, ramping up his stunts during a life stage when most people apply for AARP membership. But he’s also nodding to the recurring joke that actors can’t do even a minor stunt — let alone what Cruise does — because the insurance company won’t cover it.

Adam Driver, for example, recently revealed that, despite his starring role as Enzo Ferrari, he wasn’t allowed to drive any of the cars on the set of Ferrari “for insurance reasons.”

So how does Cruise defy the gravity of insurance policies? The studio behind MI didn’t respond to our emails, but others in the industry suggested some options:

- Cruise’s star power, plus his track record as a successful producer, give him leverage to insist on doing his own stunts — even if the resulting insurance premiums balloon the budget.

- Unlike other actors, Cruise made himself insurable through decades of training and earning pilot and helicopter licenses.

- Cruise has a stunt team he trusts and a reassuring track record of successfully finishing action movies.

Another possible explanation? Experts told The Hustle that insurance policies for Mission: Impossible may exclude the most dangerous stunts, which would mean that with every motorcycle jump or death-defying dive, Cruise and Paramount are carrying the risk of injury — or worse — themselves.

“It would be hard to imagine [Allianz insuring stunts like his],” says Furtschegger. “If everyone were to perform stunts like a motorcycle jump from a cliff, we probably would not be able to insure productions anymore.”

Still, Cruise found a way.

Tom Cruise performs a stunt on set for Mission: Impossible – Fallout filming on April 10, 2017 in Paris, France (Photo by Pierre Suu/GC Images)

Cruise’s insistence on performing his own stunts has helped him earn an estimated $1B over his career. But that doesn’t make it a playbook other actors can follow.

Barber calls him “the last of a dying breed.” Unlike the era of big-biceped action stars in the ’80s, today’s Hollywood focuses on CGI effects (a la giant Marvel battle scenes) and slick, sci-fi concepts (The Matrix).

On top of shouldering enormous personal risk, the Cruise method also takes an incredible amount of work.

“Who does a movie like Top Gun and, instead of going out partying, teaches himself how to fly?” says Barber. “And then he’ll go to the next movie and teach himself how to race a car. And then how to ride a motorcycle, how to fly a helicopter. There’s not many people on this earth who would do that.”

And not many companies that would insure it.