In November of 2001, the smell of success began to fade for Joel Bellenson.

His invention, the iSmell, promised to bring scent to the internet. He’d developed cutting-edge sensory technology, assembled a dream-team of Fortune 500 execs, and raised $20m. Video game companies, Hollywood studios, and internet giants were lining up for partnerships.

But he’d forgotten to ask a crucial question: Did anyone actually want this?

This is the story of the long, winding, unsuccessful quest to marry smell and technology — and the dangers of building something that nobody asks for.

Digital scent tech: a history of failure

Long before smell debuted on the digital tundra, entrepreneurs raced to bring it to film. The first attempts were made as early as 1906, using huge cotton balls that were dipped in fragrances and dangled in front of fans.

In 1959, two competing devices — the AromaRama, and the Smell-O-Vision — promised to create a “new immersive experience” in theatres across America.

A series of perfume containers were triggered by by cues on a roll of film; through little pipes affixed to seats, audience members were blasted with more than 100 aromas, ranging from grass to the “scent of a trapped tiger.”

Both were panned as technologically deficient, impractical, and unnecessary.

In a scathing New York Times review in 1960, Smell-O-Vision was deemed an ineffectual stunt: “The odor squirters are mildly and randomly used,” wrote the paper, “and patrons sit there sniffing and snuffling like a lot of bird dogs trying hard to catch the scent.”

They were also astronomically expensive: A full “smell rig” could cost anywhere from $15k to $1m ($124k to $8.3m today) to implement.

Ultimately, the Smell-O-Vision was ranked by Time Magazine as one of the 100 worst technological inventions in history — and would-be smell-preneurs were thrown off the scent for decades…

Until two men brought it back in the digital age

In the winter of 1998, Stanford grads Joel Bellenson and Dexster Smith were on vacation in South Beach, Florida when inspiration struck.

“There were all these hot ladies, nice beaches, good vibes — and the smells were just hitting me,” Bellenson tells us. “I took a deep breath and said, ‘Man, is there some way I can capture this and give all the other loser geeks on the internet a taste of the outside world?”

Bellenson (a molecular biologist) and Smith (an industrial engineer), had previously launched a successful gene sequencing software company. If anyone had the technical chops to digitize scent, it was them.

Their aim was grandiose: to bring smell to the internet by breaking down thousands of smells into chemical components, “encoding” them into files, and transmitting them digitally through a USB-powered desktop device.

“We wanted to create the printing press for smell,” says Bellenson. “It wasn’t just tech — it was a quest to reimagine the sensory experience.”

The duo assembled a dream-team: execs from Sega, TransAmerica, NEC, Sprint PCS, and Bath & Body Works; “scentography” experts from the perfume industry; top-level olfactory scientists, and some of Silicon Valley’s most prominent tech gurus.

In February 1999, they launched Digiscents, and set out to “revolutionize the entertainment-media space one smell at a time.”

The birth of the iSmell

In the midst of the dot-com bubble, Digiscents was crazy and bold enough to attract the attention of venture capitalists.

According to Bellenson, the company was able to raise $20m from Asian investors and build a state-of-the-art smell-dispensing prototype called the iSmell.

The device hooked up to a computer via a serial cable. Inside, dozens of tiny vials of oil — each carefully developed by a team of “scentographers” — were selectively heated and fanned out through a vent. These “primary odors” could be combined into thousands of unique scents, from orange peels to camp fires.

Avery Gilbert, a “sensory psychologist,” was recruited by Digiscents to help develop these scents.

“You can break down any smell — rotten bananas, fresh sardines — into 100 or so key fragrances,” he tells us. “From those materials, you can recreate the smell of almost anything in the natural world.”

And that’s exactly what they did.

“The porn industry loved me”

By the end of 1999, the iSmell was generating hype — for better or worse.

In October, the still-unreleased iSmell landed a scratch-and-sniff cover story in Wired magazine. They secured partnerships with Sony and Microsoft to bring their tech to video game modules. Dreamworks, Dolby, and IMAX were eager to give film integration a shot.

They were set to work with the producers of Shrek to “bring all the disgusting smells” to life, give Tomb Raider’s Lara Croft a “signature scent,” and even disrupt the porn industry.

“The porn companies were all over us,” says Bellenson. “I sat at the guest of honor table of the Adult Video Awards several years in a row.”

More than 5k game developers downloaded “ScentTracker” (a tool for interactive games), and the Digiscents website was attracting 4m pageviews per month.

There were also grand plans to launch a “scent-enabled Web portal” called Snortal, where visitors could design and send each other their own smells, and whiff in collaborative bliss.

At the same time, the iSmell became the butt of jokes.

While industries embraced it with unadulterated excitement, the public, who had yet to experience the device, seemed perplexed by how it could be used for anything other than “making custom farts.”

It also came with its share of technical faults.

“It had a fatal flaw,” one person who worked on the device tells us. “The residue from the previous smell would linger…that residue polluted the palate and turned the second (and subsequent smells) into the smell of shit.”

The downfall

Bellenson and his team were spending massive amounts of cash on “intensely systematic testing,” and further developing the cartridges, but less time actually asking the public if it was something that they wanted.

In late 2001 — just 2 years after launching a prototype — Digiscents ran out of capital, and the company shuttered.

As Bellenson tells it, the iSmell was ultimately “too complicated to get through testing.”

But Marc Canter, a tech consultant who was hired to work on “bringing the product from 0 to 1,” tells us the iSmell’s failure can be chalked up to a lack of demand.

“There was a bit of ‘If we build it, they will come’ aspect to Digiscents,” he wrote, via email.

Avery Gilbert, the scientist who worked on the scents, mirrors this sentiment. “They were constantly talking about immersiveness — it was tech boom and everyone was all pumped on what we could do,” he says. “But it wasn’t really what people wanted.”

During the peak of Digiscents’ success, a plethora of other digital scent companies sprouted up, with names like the AromaJet Pinoke (2000), the TriSenx Scent Dome (2003), the Kaori Web (2004), the Thanko P@D Aroma Generator (2005).

But when Digiscents crumbled, it took with it the confidence investors had in the success of digital scent technologies.

“Our death killed it for everyone,” says Bellenson. “And our death continues to scare people to this day.”

Today, the science, tech, and hardware for such devices has infinitely improved — but continued efforts to bring digitize smell still fall flat. Researchers across the world, from Japan to San Diego, have tried, without success, to bring the concept to market.

In the past decade, the focus has shifted from the internet to smartphones. Scentee, which launched in 2013, abruptly flopped after promising to bring “bursts of rose, lavender, and buttered-potato” to mobile.

The oPhone is currently trying to convince the world it needs scent-based text messages, and the Cyrano (a “digital scent speaker”) aims to create “smell tracks” with names like “Thai Beach Vacation,” which can be played to the aromas of coconut and suntan lotion.

“Right now, nobody’s waking up at 3 a.m. saying, ‘I really want to send a scent message,’ ” oPhone founder, David Edwards, told The New Yorker. “But one day they will.”

Will they?

Eric Ries, author of The Lean Startup, cites this mentality as one of the major impeders of successful innovation.

“The biggest source of waste in a startup is building something that nobody wants,” he said in a talk at Stanford University. “Startups don’t fail because technology doesn’t work; they fail because nobody wants what they’re trying to build.”

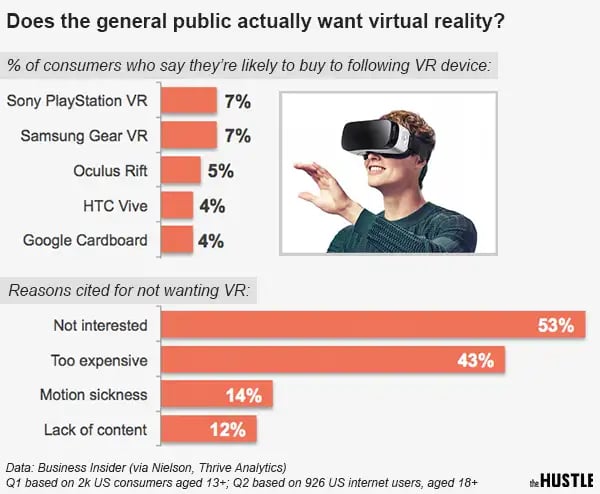

Companies still fall prey to this today (remember Juicero, or “crunch-less” Doritos?). One could even argue that virtual reality is a niche product rather than a revolutionary technology: the hype is there, but interest, by certain measures, has stagnated in recent years.

Silicon Valley has long since shifted toward a model of iterative design — releasing a product early, constantly testing it, and refining it based on the public’s demand, rather than secretly developing tech and running occasional focus groups.

The demise of digital scent companies reminds us of what can happen when public interest isn’t kept in the forefront of the design process.

Today, Bellenson’s a bit sour looking back on Digiscents’ failure. He insists the idea isn’t dead, but has merely “just been injured.”

“People just wanted to dance on our grave because we were so ridiculous,” he defends. “They were just afraid of our greatness.”

Nearly 20 years after the downfall of the iSmell, that greatness isn’t so apparent. The device is omnipresent on nearly every “worst inventions of all time” list and is universally heralded as a technological feat with no practical application — a paradigm of the dot-com bubble’s ugly bravado.

This is something Bellenson seems to take in stride.

“My old piano teacher used to tell me, ‘Joel, if you’re going to play a wrong note, play it LOUD!’” he says. “It’s better to have one of the worst ideas than a forgotten idea.”