Politicians, police, and… Panera: Geofencing is taking over

Your location data has a little something for everyone.

Published:

Updated:

Related Articles

-

-

The government vs. AI deepfakes

-

Big Tech power rankings: Where the 5 giants stand to start 2024

-

The government can read your push notifications

-

Why you usually can’t buy weed with a credit card… for now

-

Music you can really feel — no, really

-

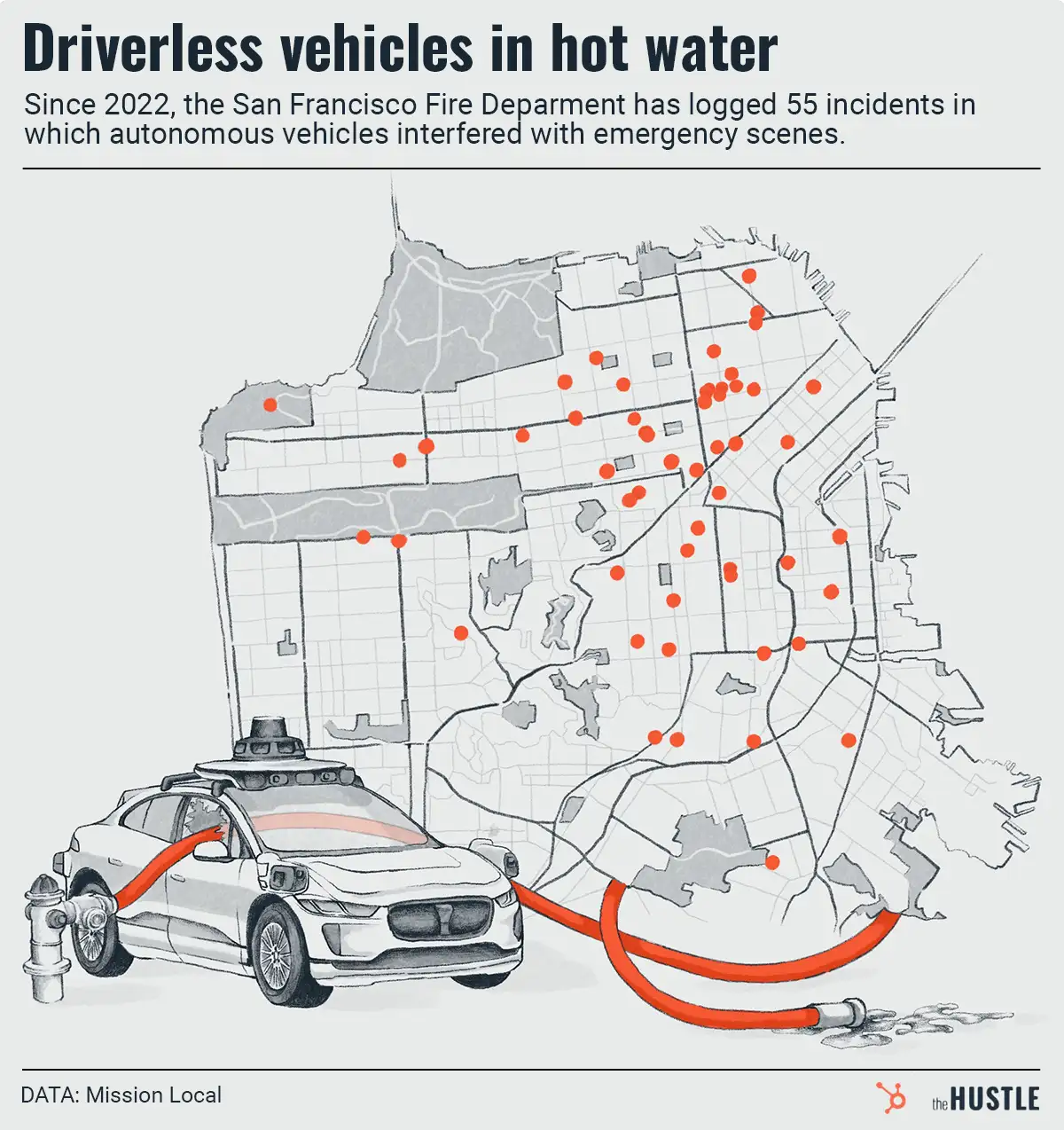

Where there’s smoke, there’s an autonomous vehicle blocking a fire

-

Meta vs. Canada is a long pattern of dismantling news

-

Is the ‘Big One’ about to drop on Amazon?

-

Enshittification just keeps happening